Leasing land is common in agriculture production for both livestock grazing and growing crops. The Extension office regularly gets questions about the current rental rate for farm ground. While the financial aspect of leasing land is important, there is more to consider than just the cash involved.

Lease agreements can be as simple as a handshake but most often should include legal advice and a contract. Contracts are in the best interest of both parties and should be revised periodically to keep them current. A contract makes both the landowner and the farm operator give thought to the agreement and develop ways of communication and understanding. It also serves as a handy reference if details are forgotten or if a death occurs.

A few items that should be given consideration are who carries the insurance on the property and/or the crop and what improvements need to occur and who will have responsibility for them. Production issues such as weed control, maintaining soil fertility, types of chemicals used on the property and ensuring the best farming methods and conservation practices should be addressed. The contract is a negotiation tool for the lease and gives protection to both the landowner and farm operator.

Since many farmers or soon-to-be farmers depend on leased land as part or all of their business, it is in their best interest to maintain long-term, positive relationships with landowners. Landowners may be dependent on the rental for income, keeping their land in farm deferral for tax purposes or simply want their land to remain in agriculture production. Landowners are seeking stable, hassle-free relations with their tenants and often want them to be respectful of the land and its history.

The farm operators can go a long way in maintaining a positive relationship with the landowner. Making an effort for a little “face time” during the growing season to visit with the owner or implementing some other form of communication is a good idea. This gives an opportunity to ask the landowner about any concerns and avoid annoyances that can get out of control. In addition to keeping in contact with the landowner, try to provide education about current agriculture practices and maintain the property's appearance. Also keep in mind the next generation, those that will one day inherit the land, and encourage them to value local agriculture.

We all know that accidents happen. Mailboxes get smashed accidentally by trucks backing out of driveways; fencing can be wiped out by a farm implement operating a little too close. Operators who take responsibility and fix the damage quickly are valued by landowners.

Note that sometimes new situations arise that are outside of the scope of the current lease agreement. It is smart to document the situation in writing, such as a letter summarizing the agreed-upon action or decision.

All contracts or leases should include a termination date so that both the landowner and operator have the opportunity to review their needs. The condition of the field at the close of the lease agreement is another factor. Some local farmers agree to flail any remaining crop residue, while others replant the land to grass for permanent cover.

There are several ways that cropland is leased or rented. The most common in the Willamette Valley is the annual cash rent. Crop share agreements are also used, where the owner receives up to 25% to 33% of the gross sales in exchange for sharing a similar level of expenses. Historically, crop share agreements were common, though cash rent is most popular now.

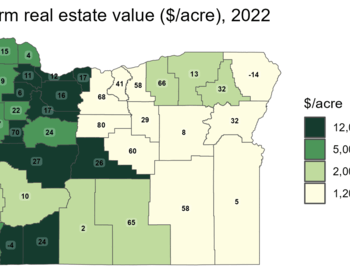

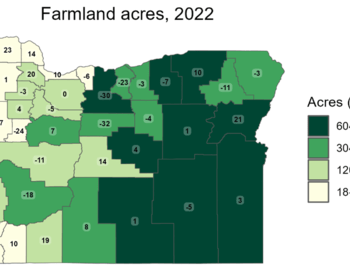

Land rental rates are driven by supply and demand, soil type and quality, irrigation water rights and equipment, and adequate fencing, among other factors. In the southern Willamette Valley, longer-term leases for blueberries and nursery crops and land for organic production are generally higher than the rates for irrigated cropland. Non-irrigated land for grass seed and other field crops brings a lower cost per acre.

Pasture rental rates are often figured by the animal size or weight; condition of the pasture, including forage quality and quantity; and the labor and equipment offered by each party. For more information about figuring pasture rental rates see Pasture Rental Rate, written by Shelby Filley, OSU Extension Service regional livestock and forage specialist.