CORVALLIS, Ore. – In every corner of Oregon, land managers worry about restrictions they may face if native bee species are listed under the federal Endangered Species Act. Knowing the status of Oregon’s 780 bee species has become a hot topic.

Oregon State University Extension Service is working to ensure federal agencies have an accurate picture of the status of the state’s bees. Starting in 2024 volunteers trained by Extension will roam the state searching out wild bees and the plants that support them. The results will provide a snapshot of the current range of each species to better assess their status prior to federal evaluations.

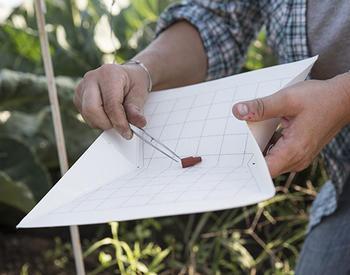

The new project, led by Andony Melathopoulos, OSU Extension pollinator specialist, will train and then send volunteers into the field. They call themselves the B-Team.

“The B-Team is based on the TV show, ‘The A-Team,’” said Melathopoulos. “They would solve any problem if you could find them because they had so many skills. The B-Team is easy to find. It’s a crack group of highly trained volunteers who can be deployed across the West to do a hardcore survey of bees. The team is designed to get the data.”

The project might be based on a TV show, but the actors are on a serious mission to document the native bees of Oregon and beyond. Their work will fill in gaps in knowledge about where bees live and the plants they depend on for nutrition and to lay their eggs, Melathopoulos said.

Data for decision-making

Accurate data will be a key factor when it comes to the decision of whether or not the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service lists a bee under the Endangered Species Act. That’s where the B-Team comes in.

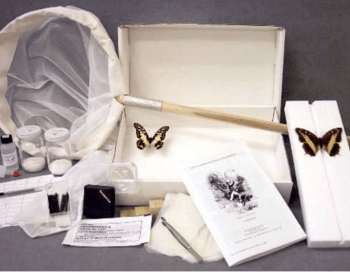

Those who complete the intense training will reach journey level as a Master Melittologist, a one-of-a-kind group of community scientists trained by Melathopoulos to collect and curate specimens of native bees for the Oregon Bee Project, a cooperative effort to document the state’s bees. The Master Melittologist program has created one of the largest data sets on native bees and their preferred plants in the world and led to countless new discoveries in the Pacific Northwest.

“We’re working toward a more data-driven land-use policy that conserves the state’s bees but assures working lands remain productive,” Melathopoulos said. “And we’re making investments in the right place, putting the money where we need it most. Tools like this will be really helpful for legislators, conservationists, policy makers and others.”

The Endangered Species Act requires landowners and managers to work the land in ways that preserve endangered species. In order to comply, they need to know if a bee species actually warrants listing and, if so, how to best aid in its recovery, Melathopoulos said.

“The key questions when considering whether to designate a bee species as endangered revolve around three questions: ‘Where are the bees? How are they doing? What habitat are they in?’” Melathopouos said. “Without precise answers to these questions, species could be listed that are, in fact, neither threatened or endangered, and working lands could be subject to restrictions that might not help the species recover.”

The U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service is charged with accepting species for the Endangered Species Act list and must evaluate whether an animal is endangered or threatened. If it is, the habitat occupied by the species might be designated as critical, resulting in restrictions on the activities permitted on private and public land. Yet the data needed to accomplish this is in short supply for Oregon’s bees. What little there is buried in entomology museum collections.

“Say a beekeeper wants to move colonies onto federal land for them to catch fireweed bloom, which makes wonderful honey,” Melathopoulos said. “They may face restrictions because of competition with a threatened or endangered bee. Or a farmer who wants to apply a certified pesticide can’t do it because their activities are within an area designated as critical habitat. Everyone is impacted. It’s important to ensure before any such restrictions are imposed, we have a clear, science-based basis for doing so.”

Knowing where the bees are

The U.S. Department of Agriculture’s National Institute of Food and Agriculture is funding the project. The training will put the Master Melittologists on the B-Team in critical parts of the West to do surveys where there are data gaps. In addition, the project involves building a tool that tells the federal and state agencies which bees are there, what plants they visit and, most importantly, where are the “hot spots” on their lands that are expected to have exceptionally high bee diversity.

If land managers knew where the bees are, they could employ enough resources to keep bees healthy and off the threatened or endangered lists of the Endangered Species Act, Melathopoulos said. Many species of native bees – close to 800 is the latest estimate – live in Oregon and some are very rare. Data would be helpful in a number of ways. If there’s a hot spot, land managers may need to exercise caution, turning their attention, instead, to areas where rare bees are not located.

“The Endangered Species Act is the law,” Melathopoulos said. “Listing species under the law has been a divisive issue, but we feel with more data and tools we can create a win-win for bees and working lands. Oregon already has one bee listed – the Franklin bumble bee. We’re expecting more. This work ensures we’re prepared.”