Transcript

From the Oregon State University's Extension Service, you are listening to In the Woods with the Forestry and Natural Resources Program. This podcast aims to show the voices of researchers, land managers, and members of the public interested in telling the story of how woodlands provide more than just trees, they provide interconnectedness that is essential to your daily life. Stick around to discover a new topic related to forests on each episode.

All right. Welcome back to In The Woods Podcast, presented by the Forestry and Natural Resource Extension Program at Oregon State University. I'm Jacob Putney, extension forester for Baker and Grant Counties and your host for this episode, we have two guests joining us today, Steve Denney, who is the coordinator of the Umpqua Oak Partnership, and my colleague Alicia Christiansen, who is the extension forester for Douglas County.

Steve, Alicia, thank you both so much for joining us today. Thanks, Jacob. Yeah, thank you. I want to give you both a chance to introduce yourselves. So why don't we start with you, Steve. Could you tell us a little bit about your background and the Umpqua Oak partnership? Okay. Um, I've worn several hats over my career. I worked for 37 years for Oregon Department of Fish and Wildlife as a wildlife biologist.

And then went to work for the Nature Conservancy, uh, for six years, uh, working on an estuary restoration project in the Coquille. And then about three years ago, I was approached to put together an oak conservation and restoration group in Douglas County and, uh, agreed to do that.

So that's what I've been doing the last three years, three years plus, I guess now. Uh, working with Oaks in the Umpqua Basin. All right, great. Uh, how about you, Alicia? How's the extension world down in Douglas County? So Douglas County is a really diverse place. Um, I cover the entirety of the county, which goes from the coast to the Cascades with the county seat being Roseburg.

And I work mostly with small woodland owners, and that's a pretty diverse crowd, as you know. So we have a wide range of interests. And land ownership types and a really big emerging one in the county is certainly landowners that have a component of oak on their property. So I have been engaged with the Umpqua Oak partnerships since it started, and I'm really excited, uh, to be able to continue working with these growing landowners in the county.

Well, great. So if you could guess it by now, Steve and Alicia have joined us today to talk about an awesome tree species we have here in Oregon, uh, the Oregon White Oak. So why don't we start off with a little bit of background. Um, so could you both tell us a little bit about this species, like where and how it grows?

Uh, its uses for wildlife or a wood product and its importance here in Oregon. And, uh, Steve, why don't we start with you. Okay, thanks. Um, you know, or, uh, Oregon White Oak is one of, uh, five species of oaks found in, in Douglas County. We also have California Black Oak, uh, canyon Live Oak, tan Oak, and, uh, saddlers Oak.

It's known by several names, but Oregon White Oak's probably, uh, one of the most important trees we have, we actually have quite a few oaks in Douglas County, primarily found at the lower, lower elevations below 2,500 feet. Although we've got a couple isolated populations and up on the North Umpqua on the South Umpqua River that are up near or a little above 3000 feet.

But they're in real specific pockets with south facing slopes and pretty thin soils. But, uh, so they're a pretty diverse, uh, tree. Probably one of the unique things about Oaks, of course, is that they produce acorns, which are really important for, for wildlife. They also provide lots of other, uh, benefits to wildlife and insect species that we'll talk about, I'm sure, uh, later on.

Uh, so, and a number of wildlife actually depend wholly on oaks like acorn woodpeckers, uh, Lewis's woodpeckers, uh, White breasted nuthatches. Some of those species. And so, like I say, it's just a really, a really unique, uh, species that's very long lived, can live 350 to 450 years old. I'm sure some reach 500 years old.

They're really drought tolerant, which is really, uh, necessary in this, uh, climate that we have now. So, and they're really fire resistant. They've, uh, evolved with fire. So really, uh, an adaptable species and, um, you know, provide lots of benefits.

Great. Alicia, do you have anything you want to add to that? What about wood products?

Yeah, what I would add to that, definitely on the wood product side, um, you know, you, a lot of people here probably don't think of Oregon white oak as really being a species that we're managing for, for wood products. And for the most part you'd be right. You know, that's something we typically see more on, um, the east side of the US but there are wood products that come from the species.

And so, um, it is certainly a popular choice for flooring, furniture and in the wine making business, barrels. Oak barrels are a really premier product out coming out of both Oregon and Washington. So, um, there's a lot of other uses for this, uh, species as well. Um, a lot of landowners love it for firewood.

It's a, a wonderful species to burn if you have, you know, some dead trees on your property, that's a great way to be able to, to utilize those that may, if they fell down and they're on your property and they need to get rid of 'em. Um, it's a great firewood species and, um, there's been other, other uses for them as well, but that furniture, flooring and wine barrel are pretty much the, the top uses for them in Oregon.

Oh yeah, you can't have bourbon without a white oak barrel. That's right. There you go. So to expand on that, uh, what's the difference between an oak h and an oak woodland, and how do you know if you have one or the other? Uh, Alicia, you want me to take that one? Sure, that'd be great. Okay. Uh, we have, uh, three and, and almost four different kinds of oak habitats.

Um, two of those being what you mentioned, oak woodland and oak savanna. We also have an oak mixed conifer, um, habitat where oaks are mixed in with, uh, cedar Douglas fir or uh, Ponderosa pine. And also we have oaks in the riparian zone, uh, over a lot of, of Douglas County, but primarily, the difference between oak woodland and oak savanna is merely tree density and canopy, uh, cover.

Uh, the oak woodland, uh, has about 30 to 60% tree cover by oak trees, uh, whereas the oak savanna is very widely spaced, great big oaks with huge canopies, but they only have about, uh, 20 to 30% of the canopies, uh, covered by oak. Uh, and those are the ones that have been managed in the past by Native Americans 'cause those bigger oaks produce lots of acorns, which, uh, the Native Americans, uh, used for, for food so.

And sometimes on oak savannas you'll even find, um, one or two trees per acre. So they can be highly scattered, uh, very, very widely spaced. Obviously, if you're only having a couple trees per acre. Um, as Steve mentioned, the management of these oak woodlands and savannas via fire is really important to maintain those densities as well.

Obviously with the differences in density, they probably have a different, uh, understory composition as well. So what species are usually found in the understory of, uh, each of these habitat types?

Uh, there, there's a number of, of, uh, understory species and we've got a group kind of working on, uh, native understory.

But, uh, there's some native bunch grasses that you find under the oak savanna particularly that are, are managed by fire. But, uh, things like, uh, California oak grass, uh, couple of the bromes, um, are also found, uh, underneath the canopy and then some, some shrub layer, like, let's see, I'm trying to think.

Snowberry uh, some of those type, there's some poison oak under some of that as well, but, uh, whereas the oak woodland has a lot more of the, of the understory 'cause there's a lot more shade involved there. So, so the oak savanna is primarily a grassland type habitat, and like Alicia said, Manny, uh, the best way to manage it is through controlled fire.

Yeah. And some other shrub species that you might find that are really common in the understory would be, uh, hazel, hawthorn, blue elderberry. You mentioned snowberry service berry, wild rose, ocean spray. Um, quite a big variety of, there's, there's others, the list goes on, but quite a big variety of understory species and, um, quite a bit of, uh, variety and herbaceous cover as well found in these habitats.

And the, and the hawthorn, the native hawthorn, not the... yes. English hawthorn, which is an invasive and really taking over parts. Yeah, that's a good distinction. North, Northern Douglas County. So, which landowners are, drives them nuts. So, but uh, yeah, it's important to know the, the difference in hawthorn when you have an oak, oak habitat on your property.

So speaking of invasives, uh, how have these ecosystems been influenced or changed over time? Uh, especially with things like climate change and fire exclusion. Well, like Alicia said, uh, Oak evolved with fire and the Native Americans burned these, um, valley floors on the Umpqua, uh, on a really regular basis.

In fact, a few of those studies I've read, uh, showed fires occurring as often as every two to four years, so really frequent, uh, fires. They did that for a couple reasons. I said that it, it helps, uh, promote those great big old oaks that produce lots of acorns, which they used for food. And then also that burning, uh, grew lots of green grass, which attracted elk and deer and bear, which they also also hunted.

So, exclusion of fire has probably been the, the number one effect on, on oaks, uh, in Douglas County. And I think, uh, other areas of the western, western part of the state as well. Uh, but also, uh, that lack of fires allowed Douglas fir and cedar to grow in areas where normally it wasn't present. And one of the things about oaks, particularly old oaks, is they need lots of sunshine.

And so when douglas fir grow up through the canopy and start to shade out the oaks that will kill them. And, uh, it, uh, they topple because of the, of a weak root system. So, so fire, fire is a big one. And then invasive species, like we just talked about, uh, in Douglas County, it's English hawthorn, uh, blackberry, Himalayan blackberry.

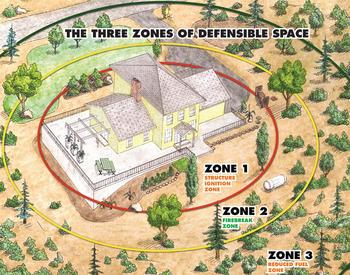

Um, Scotch Broom. Uh, some of those in particular are really taking over in some habitats and they need to be managed either with fire or, um, some understory, you know, uh, slash piling and burning, uh, that sort of thing to kind of reduce that, uh, understory canopy. So, and, and it, it, those, um, those invasives also produce ladder fuels, which allow any fire go up into the canopy, which is not what you want.

You don't want a canopy fire. So, so I say there's a number of those effects, but those three things are probably the, that have had the most impact on Oaks in Douglas County in particular. And I think one other notable one too is the land conversion aspect of another big threat to oak, um, oak loss of habitat for oak woodlands.

Um, they've been converted, uh, for a wide variety of purposes, but, you know, urban and suburban areas, agricultural land uses, while there's some ag land uses that can be compatible with oak habitat like pastures, um, a lot of them are not that compatible because they're replacing the species grown in those former Oak woodland or Oak savanna areas.

And so basically, you know, replacing that habitat, um, vital grounds cover species are removed in those situations. And so just total land conversion in those situations. Um, development is a, uh, for, you know, housing development that can be, um, a another threat to oaks in terms of land conversion as well.

And we've seen this a lot in the Willamette Valley, so north of us, where we are in Douglas County. Um, but certainly it's happened in the entirety of the oak range in the, um, Pacific Northwest Cascadia area.

Well, it seems like there's no shortage of challenges. Um, so Steve, how has the Umpqua Oak partnership been engaged to manage and conserve oaks?

Well, I think education's probably the number one thing, and that's what Alicia has helped us out with a lot. Most of the oaks, uh, are found on private land, and so, uh, dealing with a, a private landowner is essential when you're talking about conservation and restoration of oaks. Uh, the other thing that we found is, uh, you know, uh, making sure that those landowners have access to educational materials, you know, on how to manage oak woodlands, what their importance is as far as a, a key keystone species, uh, those sorts of things.

Uh, we did a, a questionnaire, uh, two years ago now, I believe. Sent out a questionnaire to over a thousand landowners in Douglas County. Kind of asked them what their views on oaks were and what they really wanted to see. And we had a, from the results, uh, the ones that were returned to us, you know, people were really interested in learning more about oaks.

They wanted to do workshops, uh, they wanted, uh, tours of restoration activities so they could see what other landowners were doing and they wanted educational materials. And so we've really focused on, you know, getting that word out. And this podcast is one of those efforts for helping get the word out to different, different communities.

But a lot of it is landowners in, in Douglas County, and I'm sure everywhere else, you know, a lot of people are buying properties have never had land before or haven't really managed a piece of property, and they're unsure what to do. And, and if we can get that education out there, most of 'em wanna do the right thing and, and manage their oaks, or restore their oaks.

And so we've been really focused on trying to get that information out to 'em. And we do that in a couple different ways. You know, Steve mentioned the workshops that we've had. We put on a two day oak, uh, workshop for landowners about a year ago last June, and that was wonderful. We had how many, Steve? It was 62.

Yeah, something like that. Yeah, something like that. Participants. Yeah. And, and so that was a great turnout over the course of two days. And landowners had on the ground, actually it was landowners and practitioners too, working with oak, um, professionally in their job. Um, we did on the ground field, trip based education as well as classroom lecture based education.

And it was really well received. Um, it was a great opportunity to, start educating landowners and, and sharing with them information about these, this, this species and this habitat type that they're managing for on their property. Um, another really cool thing that the Umpqua Oak Partnership has done to mix things up, instead of having a meeting every single month that, you know, we meet face to face and, um, discuss business.

Each quarter we say no business meeting and we have a field trip instead. And that has been wonderful getting out onto the land, um, and seeing these different properties and the different ways that people. Of all sorts of ownership types and structures too. Um, seeing how they're managing their land and what challenges have they faced, and it's an opportunity for that peer-to-peer networking and peer-to-peer learning environment that I think is really powerful for people to get ideas and gain confidence and start to feel comfortable with putting some of these practices on the ground on their own property.

So those field tours have been a really powerful thing in the community and, um, have reached a wide variety of people working and managing with oak in Douglas County. Perfect example of that is, uh, one of our tours. Uh, we have a lot of mistletoe in our oak trees here.

And, uh, a lot of questions whether the missile toe is, is harmful to the oaks. Uh, you know, does it need to be cut out? Does the tree need to be cut down? And we had one of the west and maybe even the US, uh, experts in oak mistletoe. And yes, there are experts about, uh, oak mistletoe, but came and, and gave us a tour and we looked at.

Heavy, light and medium infestations, but we found out that, you know, uh, it's parasitic to oaks, but it doesn't, uh, it, it may reduce their vigor, but it doesn't tend to kill the oaks. But also that mistletoe is really important to like over wintering birds, like blue birds and others that eat the berries in the wintertime and use the, the, uh, mistletoe clusters so that, that it is just those types of educational opportunities for a landowner that I think are really important.

And like I say, we got, we got, uh, one of the renowned experts in, in Oak mistletoe to, to get us up to speed on what, what it is and, and how it works, uh, with Oaks.

No, that's great. That's really exciting to hear, uh, such a great program and um, it sounds like an exciting field tour as well. Um, but I guess on the, the other side of the successes, what about some of your biggest, uh, barriers or challenges to this effort?

Well, I think, and Alicia can chip in here as well, probably just, you know, most people just don't know how important oaks are. And so, you know, oaks have been cleared for forever, I guess since, since the pioneers were here for, as Alicia said, pasture and agriculture and for towns and, you know, subdivisions and that sort of thing.

But, uh, most people just you know, I think a lot of people just feel oaks are, are kind of in the way and, you know, they might be good firewood, but really not good for anything else and just trying to get that education out there. Uh, and so that's been, like I say, the main focus and the fact that oaks are mainly found on private lands in the Umpqua Basin.

So, so that's, that's probably been the biggest barrier. But to be honest with you, uh, I've, I've gone out, reached out to all the landowner groups in Douglas County, or not all of 'em, but many of 'em in Douglas County, like Farm Bureau and Livestock Association, small Woodlands, those folks. And there's really an overwhelming interest in, in Oaks, and I think, and once we explain, uh, the importance of oaks, you know, they all are really excited about doing some things.

Not all landowners, but you know, each landowner has a different objective for their property. But if we can get 'em the right information, let them make their own decisions, I think, uh, we'll be better off for it so. Alicia, do you wanna chip in anything? No, that was perfectly said. Okay. And it was, it was exactly what I would've said.

So speaking of landowners, so if there are folks who have oak woodlands or savannas on their property, uh, what are the, some things they can do to protect or enhance these areas? So there's a lot of different things that you could do. Um, I'd say one of the, one of the big ones would be preventing encroachment from conifers.

So, um, if you're noticing that Douglas Fir or Grand Fir are starting to kind of creep into your oak woodland, or maybe they are already there in a more mature, uh, form, managing those species and, uh, clearing out or thinning those species to promote the oak growth would be a really great thing to do to try to maintain those oak habitats.

Steve mentioned, you know, one of the big threats was conifer encroachment. These oak trees, they require sunlight in order to survive and in order to thrive. And if there is a shaded canopy above them, which conifer trees generally are going to grow taller than an oak tree. So a shaded canopy is inevitable because conifer trees also grow faster than oak trees.

So these oak trees just don't stand a chance to be able to survive in a situation where conifers overtop them and shade them out. So it doesn't mean that you can't have a mixed conifer in oak woodland. That is certainly one of the forest types that Steve described. Um, but being thoughtful about how you manage that and maybe thinning out conifer trees that are around your oak trees that you're trying to protect, and maybe having a more patchy nature where you have some patches of oaks that you're trying to keep.

And then some patches of conifers that might not be indirect competition for the oaks. So that would be, um, one really great tool that a landowner could use to help maintain their oak woodlands. Um, if they're in a situation where, uh, conifers are growing up through an oak, for example, that can be pretty tough to fall if you're trying to actually thin out the physical tree from that oak tree.

Take out the conifer from the oak, so, in those situations, especially, um, if these conifers are larger in size, growing up through an oak tree, girdling those conifers and leaving them in place. But girdling, um, severs, the cambium of that tree prevents that tree from growing anymore and it will die creating a standing dead tree or a snag.

And those snags are fabulous for wildlife. And so you can achieve multiple objectives if, um, that is your situation where you have mature conifer growing up through your oak woodland, you can still try to start to come back from that. Steve, would you have anything to add on? I know there's more.

Yeah, a couple things just with the, with the climate change we're facing now and the, the drought that we've been subject to, uh, we've really had a lot of the firs on, especially on south slopes, die.

And so, you know, that's actually benefited Oaks, uh, Uh, by and large, but if people do want conifers, you know, they could plant ponderosa pine. It's a lot more open, growing, uh, type of a tree rather than doug fir or incense cedar. And, um, I think oaks tend to get along with them a lot, lot better. Uh, the other thing is removing those endangered or those invasive species underneath the canopy.

It not only, um, will help prevent fire, which I think we're all concerned about the catastrophic fire now, but also, uh, gives more room for native understory plants and, and helps, uh, reduce those ladder fuels that, uh, would help promote a, a canopy fire. So those are some things that, that individuals can do.

Um, ironically in town, you know, one of the biggest threats to oaks is over watering people water their lawns and, you know, oaks don't handle a lot of water. Uh, well, and so, uh, you know, watching how they, how they water their lawns. So, you know, we're even individual oak trees are important. Some of the studies have shown that, you know, an oak tree in somebody's backyard, has all the benefits of oaks out and, you know, on, on a rural, you know, a hundred acre, uh, property.

So, you know, saving those individual oak trees, especially in town, creates a huge diversity of, of, uh, wildlife benefits and um, uh, for birds and, and, uh, invertebrates and even things like gray squirrels and those sorts of things. So, uh, all of those would benefit oaks in the long run so. And for maintaining those or preventing those and managing against those invasive species that you mentioned growing up in the understory there competing with the oaks.

Depending on your specific landscape and your situation, um, the configuration of the density of the trees in your forest, there's different ways you can go about managing for that. Um, you know, a lot of people think of chemical treatments as being the, the first thing that you might do to help tackle those invasives, but, um, there are other methods that you could apply as well, and not only to get rid of those invasives or to slow them down, but also to promote the native herbaceous and shrub understory that we would find.

And also control conifer seedlings that might be popping up. So grazing with livestock, that's a great option. Um, mowing with, uh, mechanized equipment, that's another option. And then prescribed burning. Those are all things that could be done to in, and even in conjunction with each other. All of those things could be done to help manage against invasive species and manage for the oak and the future of that oak habitat.

And so, like I said, it's really gonna depend on the specific property and, um, the resources, uh, available to that landowner. But there are a variety of methods that you could employ to get that work done.

Yeah, that, that maintenance, once you've done all that work to remove the invasives and either pile 'em for burning or whatever, but about every three to five years you need to go back in there else.

You'll just get taken over again with, uh, Blackberry or hawthorn or Scotch Broom, whatever you've got. So you gotta maintain it. And it's a lot of work, you know, for a landowner. But you know, if you care about your land and, and the native species around it, uh, You know, uh, to me it's a labor of love. So those are all things that you need to do that can benefit oaks.

Alicia, you beat me to it. I was just gonna ask what opportunities there are to reintroduce fire into some of these ecosystems. Oh, yeah. Prescribed fire, definitely. And that is, a barrier for a lot of people. But OSU extension, um, the Umpqua Oak Partnership, local Fire Protection Districts, um, at least in Douglas County, there are a lot of conversations going on.

And Steve, you could speak more to this about the specifics, but, um, there's a lot of, uh, pre-work being done right now to figure out how to make prescribed fire a accessible tool for landowners to maintain their oak woodlands. Uh, yes, uh, specific. Sorry. Phone rang there. That's okay. Uh, but yes, uh, uh, you know, we mentioned the workshops that we're gonna, uh, we've been putting on and one of the next ones we're talking about is a fire workshop with, uh, some of the landowners.

We've even identified an area to, to do a demonstration burn, uh, hopefully in July if it's dry enough. But, uh, uh, those sorts of things, uh, we talked about with, uh, OSU extension about doing some, uh, uh, getting a, a fire, uh, uh, what's the name of it, Alicia, with the, uh, fire, the, um, prescribed burn association.

Yeah, there you go. Yes. Prescribed burn associations where a group of landowners get together and share equipment and knowledge and funding and um, uh, those sorts of things with the local, uh, fire protection agency. And so that it's almost like a branding or something else where everyone gets together to do controlled burns on hopefully a number of different properties, some of the bigger local, uh, uh, grazers, uh, here, cattlemen, uh, burn on a regular basis and they do that similar thing.

So we've got kind of a basis to, to work from, uh, to form some of these fire associations. We think it's really got some good, uh, potential.

Well, I think you mentioned a lot of great ones already, especially with some of the, uh, workshops and field tours and stuff, but what other resources or tools, uh, might be available for achieving management objectives related to this species?

Well, we, we've, uh, as part of, uh, what we do when we meet with landowner groups and that sort of thing, we have a, a number of, uh, different handouts, uh, landowner guides. Uh, uh, we've got three or four of those different that landowners can look through to get information and places to go for additional information.

You know how to grow your own oaks from acorns and transplant 'em. If you want to, uh, go from that, go that route. And I've done that on my own property, uh, collected acorns and grown seedlings and transplanted them out there and protected 'em from, from deer damage. So, uh, there's a number of, uh, different things that we have available to landowners.

And then Alicia, of course, uh, through extension has got a lot of information too. We're working through Small Woodlands Association. They've been a big supporter of the Umpqua Oaks Partnership ever since, uh, we got started. And so they've got, they're always sending out information on their website. Uh, you know, everything from, uh, uh, fire levels to, you know, they do their own, uh, tours and workshops and that sort of thing.

So, uh, we've been able to work together with them on a number of, uh, different things. And I would say, in addition to all of those great resources in general, your local Oak partnership could be a great resource just to start with. I mean, I know all the listeners of this podcast aren't going to be in Douglas County.

I imagine they're spread pretty far and wide, and so if the Umpqua Oak Partnership isn't relevant for, for you, uh, if you're in an area, at least within the Pacific Northwest Cascadia region where Native Oak habitat exists, um, there is likely an oak partnership that you could engage with and learn more from and get on their mailing list and attend tours and get email updates, and you can learn a lot that way.

And I'll just reiterate as a part of that, that peer-to-peer learning and just being in the room with a bunch of other people that are addressing similar concerns as you have, um, or addressing similar management goals that can be really powerful and really educational for a person. And so I would just encourage anybody to, um, connect with their local Oak partnership, and if you don't know who that is, you can um, turn to the Soil and Water Conservation District in your area to find out who might be doing that kind of work.

Yes, we're, uh, we're one of five different oak groups in Oregon right now. Uh, we were the last one to form actually, but, uh, we do have one down in, uh, Klamath Siskiyou, uh, uh, uh, based out of, uh, ca or out of the Medford area.

It's called KSON, Klamath Siskiyou Oak Network. We have the Umpqua Oak, uh, partnership. There's an oak partnership in the Willamette Valley, one up in the greater Portland area, and then one in the lower Columbia that goes all the way up to the Dalles and takes in actually both sides of the Columbia. So it actually goes into Washington a little bit.

So, and I, I'm sure, in fact, I know there's other oak groups in Washington and California, particularly Northern California. So, uh, you know, they're, they've kind of popped up in all different areas where, where oaks occur and like Alicia said, getting a hold of them would be a really good first step if you wanna learn more.

Okay, well we are nearing the end here, but I wanna make sure we don't miss anything. Uh, do either of you have any parting thoughts on oaks, these oak habitats, the partnership or anything else you'd like folks to know?

You know, one thing that I hear from people a lot when they become interested in oak habitat and oak management, and how do I support that on my property is the question of how do I grow more oak trees?

And Steve, I think is a good resource. You know, you have a lot of experience doing that on your own property. Um, and it's kind of a trial by fire situation it seems for a lot of people. I hear a lot of, um, you know, you put in a lot of effort, um, for a little bit of reward for what that effort is.

So what I would say is that, it seems, and Steve correct me if I'm wrong, but it seems that oaks can be a little finicky to propagate. Um, they definitely prefer to root where the acorn falls and they're gonna grow best in that spot. But should you be in the situation where you wanna grow and propagate some own oak trees of your own, um, collecting the acorns at the right time is gonna be pretty critical.

So you wanna do that, um, in August or September, and you just collect them off of the ground and then you, um, don't wanna collect more than 20% of the seed that falls off of a tree. And that just helps preserve genetics in the ecosystem, food on the landscape for wildlife. And it also can be really beneficial to collect oak acorns from a variety of spots on your property or from the area that you're collecting again to kind of increase genetic diversity.

And so there, uh, is information out there that we could share with you on oak propagation of seedlings. But, um, doing that can be just so, just so it, it's out there in this podcast and everybody knows it can be a little tricky and they're not all going to make it for a variety of reasons. So plant a lot more than you are wanting to put back out on the landscape just to make sure that you have, um, a good number pop back up when you do transplant them out there. Steve, do you have anything that you'd wanna add to that? Words of wisdom?

Yeah, oaks are not a consistent mass producer. They don't produce acorns every year, and some years are, are better than others. I've always kind of said the rule of thumb in Douglas counties, we have a really good mass year, about every two years out of five, uh, depending on the spring.

But, uh, uh, oaks are relatively easy to grow, I've found, but transplanting them is a little bit different. Uh, but, uh, we do, um, you can go out and take the acorns and just dig a very shallow hole, just an inch or two deep and put acorns in there. Acorns are relatively easy to tell, viable acorns. You just put 'em in a bucket and fill it with water in the bad acorns, float to the top 'cause they've got airspaces in there.

The good acorn sink to the bottom. So you can eliminate, you know, all the bad acorns and just deal with the most viable ones, but you can dig 'em in a shallow hole or put 'em in a depression, um, that way. Uh, I've also given, uh, the oak talk to the master gardeners here in Douglas County, and they were really excited because we don't have a good source for locally, locally grown oak trees.

And so they're looking at taking that on either for giveaway or for, um, or for sale. I'm not sure which they're gonna do, but, uh, be able to, uh, have oaks available, seedling Oaks available, uh, to people that want 'em.

So I say just so there's a variety of things we're working on to try to get that word out there, but it is. It's a great tree to, you know, get kids involved in, you know, if they can grow their own. We've had some, some luck up at, uh, Sutherland, at Ford's pond of a FFA group, uh, raising their own seedlings, transplanting them out at, at the pond and trying to reestablish those oak woodlands.

So lots of opportunity for kids to get involved in, in oaks, whether it's helping remove invasive species or, or, um, growing their own. So, uh, those are all options we could take a look at.

All right. Well, that's great. Oak is such a neat species that we have here in Oregon and it's exciting to see such an effort to restore and conserve, uh, these ecosystems in these different habitats where it's found.

So, Steve, Alicia, I wanna thank you so much for sharing your expertise with us today. Uh, if any questions came up while you're listening or if you'd like to learn more, please drop us a comment or send us a message on our website. And before we wrap up here, we'd like to conclude each episode with what we call our lightning round, or a few questions we ask each of our guests.

So Steve, let's start with you first. Uh, the first question is, what is your favorite tree? I know this is a loaded question I'm supposed to say oak, but I'm gonna, I'm gonna say two different tree species. One is Oregon white oak because I, I, I, uh, they're really important for a wildlife species. For wildlife species.

And since I'm a wildlife biologist, I, I really am attracted to those. But they are a keystone species and really important. But I'm also really fond of sugar pine. I just think they are really a neat tree. They grow to huge size. They got huge, uh, pine cones and so I really like, uh, uh, sugar pine as well.

So, so I'll give you two, two species. Uh, yes, I know it would be, uh, kind of sacrilegious if you didn't say oak, I suppose, right? Yes. Since I'm the head of the Umpqua Oak partnership, I probably wouldn't go for very well. Um, so the second question then is what is the most interesting thing you bring with you to the field?

Interesting thing. Well, lately, I originally would say binoculars, but uh, recently I found an app, uh, from Cornell University called Merlin, and it is an app they've developed that allows you with your phone to hear bird calls and identify the species. Uh, it identifies a species for you. It's fascinating, uh, to use.

And so I've been using it a lot in, in the oak woodlands on our farm, uh, trying to identify what kind of species are using the oak oak habitat. So, and, and it also plays calls as well, so you can kind of call birds in and that sort of thing. So I've turned some people on, including my mother-in-law and my son, and, and they just love it.

And, uh, it's really fascinating to turn it on and see what all those bird calls are 'cause I'm not very good at bird calls. Pretty good at visual identification. But, uh, anyhow, I guess that's, that's my most interesting thing. No, that's neat. Does it work really well? Like picking up the sounds and stuff?

You know, it, it's, it's accurate near as I can tell, about 90% of the time, but every once in a while it'll, I, I'm in an oak woodland. Far away from much water. And the other day I got a Bonaparte's gull to show up. I don't know where that, how that happened, but on some of the, the weird species that pop up, I usually have to go see 'em before, I'll think that they were actually there.

That that one's an ocean, ocean type bird. So, but uh, but it's, it's remarkably accurate and it's, you know, what is, it can pick up calls in the background that you're not really focused on. You always focus on the loudest calls and it'll, it'll hear some other ones use the, well, where's that at? And pretty soon you kind of tune your ear and, and all of a sudden you'll hear that other, other bird, whether, you know, a warbler or Yellow-bellied woodpecker or whatever it is. So, so that's a, it's a really neat app and it's free, so, yeah.

That is neat. Yep. All right. And then the, the last question we have is, uh, what resources would you recommend to our listeners if they're interested in learning more about all things related to Oak? I know we mentioned a bunch already, but if there's anything else you'd like to plug.

Yeah, yeah. There's one here that, that, if you're really interested in Oaks and, and I can show you a copy, but there's a book called The Nature of Oaks. It's by Douglas Tallamy. Uh, he's kind of the godfather of oaks. He is, uh, done a number of things. He's actually got, I think, some grandkids or a or kids in the Portland area.

So he comes out to the West Coast every once in a while. But, uh, that one's a real neat, uh, look, it's not, not, uh, overly scientific, but it runs through the 12 months in an Oaks life. And, uh, talks about some of the things he's done over 40 or 50 years with Oaks on his property back on the East Coast. But, uh, a lot of the things that he mentions, uh, on Oaks back there are applicable to oaks out in our country.

I mean, an oak is an oak, but, uh, uh, that's a, that's a really neat one that, that you can get ahold of and take a look at. Great. Well, I'll have to, uh, put that title that, and link it on our website. Um, all right, Alicia, it's your turn. So, first question, what is your favorite tree? Okay, well, I'm glad. I'm glad Steve said Oregon White Oak, because while I love Oregon White Oak, it is not the number one on my list.

Um, at least overall it's up there in my favorite hardwoods. So my favorite overall tree is a Ponderosa pine. I think that there's nothing like walking through a nicely managed, wide spaced ponderosas pine forest and setting up a tent, and maybe you're on a creek, need to do some fishing. I think that is my favorite place to be on this planet.

So ponderous pine. That's a good answer. I don't know if some of your constituents in Douglas County might agree, but. Yeah, I'm not sure that they would either. But on this side of the Cascades they would probably, oh, they definitely would. Well, everyone thinks that, uh, you know, all we have is Doug fir over here, but we've actually got quite a few Ponderosa pine we do even in the valley floor here, so, yep.

The next question is, what is the most interesting thing you bring with you to the field? So I'm following Steve's lead on this one with an app because I think that that is a, a really cool way to address this question. So, um, I had, I couldn't, I couldn't decide, and there's two apps on my phone that kind of serve similar purposes that I really enjoy referring to.

One of 'em is Avenza Maps. And the other one's, onX Hunt. Um, you know, both of those are extremely useful. When you're out there, a venza, um, shows you where you are. You don't need a satellite. Uh, you don't have to have, you know, an internet connection or, uh, LTE or anything like that, you know it, it works in remote areas and you can do it like you do your Google maps.

It has your little blue dot and it follows you around and so you can mark the trail that you went on or mark a cool feature that you find when you're out in the field. So I find Avenza to be really useful. Also, a really great tool for landowners to map on your property and pick out different features.

And then onX is really great. That shows, um, land ownership. That's the feature I like most about that. And that can be really useful when you're out wanting to know, you know, who are our adjacent property owners, um, that type of thing. So in conjunction, I find those to be pretty great field tools. I don't, I don't think I could survive without either of those apps.

Yeah. So I use them all the time. I bet. All right. And then lastly, uh, are there any other resources that you'd like to recommend to our listeners?

So I'll reiterate the, um, what, what we mentioned earlier about just if you're really interested in learning about oak and engaging on a local level, find out if you have an oak partnership that you can connect with and, um, start learning more with that partnership.

But kind of on a broader scale, if you're in this. Um, Oak Range extending from, you know, Oregon all the way up through Northwestern Canada, this Cascadia region of, of Oak area. There is a listserv, well, there's actually, it's a organization called, CPOP, uh, Cascadia Prairie Oak Partnership. So this CPOP has a listserv, which is just an email list anybody can sign up to be on.

And what is really cool about this is it's a community of people and organizations that are involved in all sorts of different levels of prairie oak conservation and species recovery efforts in this region. And this listserv kind of acts as a place for people to ask questions and talk about best management practices.

They'll post related job openings and conferences, and workshops, share, share newsletters, relevant publications. And so it's a really diverse, well-rounded, uh, Resource, if you wanna just dive in and see what are questions practitioners are having around oak, they're talking about it on that CPOP listserv.

Now, your inbox might get flooded a little bit if there's a topic that a lot of people are really interested in. And so you might get 20 emails on this one thread of conversation, but you'll learn a lot and I think that's been a really great tool. For, for myself to kind of further educate my own knowledge on oak outside of just my specific area.

No, that's great. Uh, well, Steve, Alicia, uh, thank you again so much for joining us today. I, I really, definitely learned a lot, uh, particularly the Oregon White Oak has always been a favorite species of mine. Uh, my grandparents had a number of them in their backyard, and I just remember I spent a lot of time as a kid picking up acorns and collecting them.

I don't remember what I did with all of them, but I picked up a lot of acorns when I was younger. Well, uh, this concludes another episode of In the Woods. Thank you all so much for listening. Don't forget to subscribe and we will see you all next time. Bye everyone.

Thank you so much for listening. Show notes with links mentioned on each episode are available on our website inthewoodspodcast.com. We would love to hear from you, visit the tell us what you think tab on our website to leave us a comment, suggest just a guest or topic, or ask a question that can be featured in a future episode. And, also, give us your feedback by filling out our survey.

In the Woods was created by Lauren Grand, Jacob Putney, Carrie Berger, Jason O'Brien and Stephen Fitzgerald, who are all members of the Oregon State University Forestry and Natural Resources Extension team. Episodes are edited and produced by Kellan Soriano. Music for In the Woods was composed by Jeffrey Hino and graphic design was created by Christina Friehauf.

We hope you enjoyed the episode and we can't wait to talk to you again next month, until then what's in your woods?

In this episode, Jacob Putney is joined by Steve Denney and Alicia Christiansen to discuss the importance of educating the public about Oak trees and their positive impacts on Oregon's woodlands.