Transcript

Andony Melathopoulos: [00:00:00] There's an aspect of pollinator protection that often goes overlooked because it seems to have nothing to do with pollinators. What I'm talking about is keeping invasive insects out of an area. Now you'll remember, we had an episode with Dr. Dave Smitley from Michigan State University, where he made the bold claim that actually we can manage most of our pests without using a lot of insecticides if we kept those exotic insects out.

Now, one insect that's of particular concern here in Western Oregon, but also for listeners in other states, is the Japanese beetle. And I thought this would be a great opportunity to bring a close friend and collaborator Dr. Jessica Rendon from Oregon Department of Agriculture.

She wears many hats, but one of the hats she wears is she's a Japanese beetle eradication specialist. This beetle causes devastation in its path. We're going to hear about efforts that Jessica is involved with to eradicate this beetle from around the Portland area. In addition, we're going to wrap around to the end of the episode where we're going to get bee geeky.

Jessica knows a lot about native bees. And so at the end of the episode, we'll turn our beetle hats off and go back to bees. Anyways, I'm really excited for you to get this episode, Jessica Rendon from Oregon Department of Agriculture this week on PolliNation.

All right. I am so pleased to have with me today, Dr. Jessica Rendon from Oregon Department of Agriculture. Welcome.

Jessica Rendon: [00:01:24] Thank you. And so nice to be here.

Andony Melathopoulos: [00:01:26] We work really closely together on the Oregon Bee Project. You are the representative on the steering committee of the Oregon Bee Project, and we talked just last week; we were working on phase two, the second strategic plan for Oregon.

Jessica Rendon: [00:01:42] Yeah. Yeah. We've been working on that now and I'm really excited. All the edits we go through each time it gets better and better, and I think we're getting really close to having that final document for the coming years.

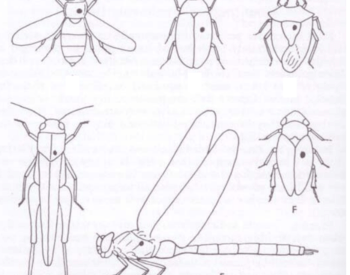

Andony Melathopoulos: [00:01:54] I was so excited. I got an email from you just a couple days ago, and you had all the entomologists over there in your division, and you came up with a list of Oregon pollinators. It was very fascinating how many different pollinating species outside of bees there are.

Jessica Rendon: [00:02:08] Yeah, it's not just bees. You got some beetles, and flies, some moths. They are they get overlooked, but they're doing some pollination too.

Andony Melathopoulos: [00:02:16] And that list, it's great. It was a nicely put together list and that list will be in the next strategic plan. So when it comes out, folks, you really want to check it out. Okay. But we're not here to talk about pollinators; we're talking about something related to pollinators, and you have been working really closely with Oregon Department of Agriculture and Japanese beetles.

Why, if people are worried about pollinator health, why do you need to be worried about Japanese beetles?

Jessica Rendon: [00:02:46] So Japanese beetles, they're an extremely invasive insect that the Department of Agriculture we're always on the lookout for. One of the reasons is because they will be completely devastating to almost all of our crops, and ornamental plants that people have in their yard.

And what would come from that, if the beetle were to become established in Oregon, is a huge increase in pesticide use both in the agricultural nursery sector and in just people's residential yards. Pesticides can be a really great tool when used properly, but if we can avoid having to use them in perpetuity that would be preferable.

Invasive species, like the Japanese beetle are something everyone should be concerned about, especially if you're concerned about pollinators.

Andony Melathopoulos: [00:03:34] I remember we had a past episode with Dave Smitley in Michigan, where Japanese beetle is a problem, and I remember him pointing out that if we didn't have invasive insects in some ways, when it comes to horticulture industries, we probably wouldn't have to use that much pesticides.

It's really those invasive insects that kind of like bump pesticide use up.

Jessica Rendon: [00:03:56] Yeah, definitely. Invasive species, when they get to a different area or an area they're not supposed to be in, they don't have any specialized predators that are gonna provide a top-down control so then it gets up to us as people to have to provide that control often in the ways of chemical control unfortunately.

Andony Melathopoulos: [00:04:18] Okay. So Japanese beetle, it seems like it's been knocking on Oregon's doorstep for a couple years now. Can you describe the history of Japanese beetle in Oregon and where current efforts stand at eradicating it?

Jessica Rendon: [00:04:32] Yeah. So Oregon has a very long history of looking for and battling the Japanese beetle.

I think we've been trapping in Oregon for 70 years or something. And then, the 1980s, I think is when trapping became bigger. More traps out there specifically for the Japanese beetle. So we've been always looking for it. In the eighties in Cave Junction and in Tigard there were a couple of smaller eradication, successful eradication events.

I think again, in Cave Junction in the early two thousands, there was another population that was found. But again, we were able to successfully eradicate it. So yeah, Oregon has had a history of finding the beetles and eradicating them for many years. We always find a few beetles at the Portland airport; they're often brought in as stowaways on air cargo.

Finding beetles here and there and taking care of them is nothing new for Oregon. However, in 2016, that was the big year for us. We found 369 beetles in the Cedar Mill Bethany area of Oregon. And that was a huge amount of beetles to find in one area.

So since 2016, we've been in a full scale eradication mode, trapping for the beetle, and higher level density trapping where the beetle is in the Cedar Mill area and doing our eradication where we use targeted insecticides on people's lawns to reduce the population there and hopefully eradicate them completely.

Andony Melathopoulos: [00:06:15] Tell us a little bit about what we know has been going on with that population since 2016; it seems like it's contained, but is it?

Jessica Rendon: [00:06:22] Yeah, let me bring up my little slide on my end that shows the numbers. So, the short answer is yes, we are decreasing the population. If we continue with this decrease, we'll be able to eradicate them.

However, It's a really a year to year thing. So just for example, last year, 2019 compared to 2020, we reduced the overall population by roughly 45%. The year prior, we reduced it by 56% overall. So that's really great. Last year we found only 4,490 beetles total, which is great that it's going down so much.

However, this last year and the year prior, what we find is we find beetles spreading out from that main area. And so that is really a challenge and concerning, because even though we're decreasing the population, if we continue to see spread, it just makes it so much more difficult to contain. But at this point in time, we still believe we can do it.

But it's, we just have to play it by year to see what our chances are.

Andony Melathopoulos: [00:07:40] Okay. Tell us what the future may hold in store, but can you walk us through the different tactics that ODA employees to get towards eradication? And I particularly want to focus in on what steps are being... obviously killing an insect... there's bees all over that area. What steps are being taken into ensure pollinators are minimally impacted by the eradication efforts?

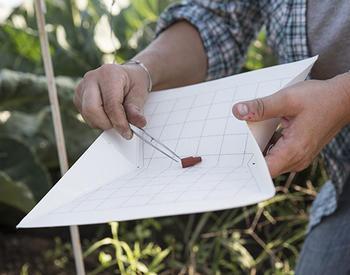

Jessica Rendon: [00:08:06] Yeah, so our eradication is two pronged. So we trapped for Japanese beetles throughout the state always, and specifically where the beetle is known to be we trap in higher densities.

So hopefully when the beetles go into the traps, they're not able to mate and reproduce, so hopefully that is one way of reducing the population. But the major way we're able to attack this beetle is through the insecticides that we use. So our first main line of defense is treating turf grass and ornamental planting beds with acelepryn G. It's a targeted insecticide for white grubs in the soil. And then a second or third tactic, is we spray foliage of plants that the beetle likes and where the beetles are the highest density to help reduce that population. It's a one, two punch between the granular and the foliar spray. So yeah, trapping and the treatment is our main two ways of trying to get this beetle under control.

And going back to pollinators; they are one of our main concerns for the Department of Agriculture. So many of our agricultural plans or specialty crops are dependent upon honey bees in particular, to pollinate them. So yeah, that's obviously a major concern. I'll start with the traps. So the traps themselves are not really attractive to pollinators.

We do find some bumblebees and honeybees in them here and there, but it's such a minuscule amount. I'm sure your listeners have heard, driving your car kills so many more insects. And so the amount of by-catch we have in our traps is so incredibly small. And I think last year, the USDA, and some other researchers did an experiment to see what color of Japanese beetle traps and what lures would be the least attractive to pollinators. And the color traps we use, the green, all solid green, are the least attracted to pollinators. And the lure I had to double check if our lure is the one they recommended, for least pollinator bycatch, but that came out last year, two years ago. Yeah. And then, so then getting back to pollinators and the second side of what we do the pesticide application...

So in 2016, when they found the Japanese beetle in the Cedar Mill area, our task force came together between ODA, USDA, other organizations in the state to figure out what would be the best course of action and products to use, of course considering the environmental and human impact. And so that's how we chose the product we currently use: acelepryn G, because it's known by the EPA to be a reduced risk insecticide for people, pollinators, wildlife. There's no caution words or re-entry period of the product. And there's no... many pesticides have those little bee boxes that say what to do to minimize the impact of pollinators. Because acelepryn already has such an incredibly low negative impact that there's no special thing you have to do.

Andony Melathopoulos: [00:11:40] Acelepryn, in the pesticide training I do around the state, we'll often have exercises, and acelepryn is one of the exercises because there is not even in environmental hazards does it mention bees. When there is potential for bee exposure, it is one of the better products to use.

That's great. And I guess the other thing is it's in a granular form, so it's going right into the soil.

Jessica Rendon: [00:12:03] Yeah, exactly. The bees aren't, and there's no flowers in the dirt.

Andony Melathopoulos: [00:12:08] Okay. But then you also talked about the foliar treatments and those, I guess, you're finding a persistent hotspot and then if you didn't do that, the beetle will get away.

Tell us a little bit about that.

Jessica Rendon: [00:12:22] Yeah. 2019 and 2020 where are two years where we used the foliar spray. It's just an attempt to get a handle on the population. We only spray roughly 10 or so plants species, the ones that are most attractive to the beetle. And we're only treating a very small subset of the overall treatment area.

Just again, to be as cautious and environmentally conscious as possible. If we're going to use a spray, we want to do it the least amount, but the most impactful to get rid of the beetle. And overall, if we don't stop this beetle, the increase in pesticide use is going to be... yeah. I don't like to think about it. I hope we can avoid that situation.

Andony Melathopoulos: [00:13:13] I guess that's my last question for you is what's ahead for 2021? I imagine, something like a big, large eradication project that involves going into homeowner's backyards during a pandemic was a challenge for ODA.

So what's that head for 2021? You're probably in the depths of planning this whole thing again.

Jessica Rendon: [00:13:39] Yeah. Yeah, we are. The ball is rolling all over again. We're going to do pretty much the same thing we did last year, essentially. We are finalizing our treatment map based on where, and how many beetles we caught last year.

We're almost finalized with that. And then we'll start sending out consent letters to all the residents that are in the treatment area, and we'll have to play it by ear how we do our outreach. I think we're going to do some webinars for people to attend. Obviously we don't want to have people coming into a room, hundreds of people in a room with us, so we'll be sending out some kind of outreach in that way.

Andony Melathopoulos: [00:14:21] I remember early on in the program, what was remarkable, is that ODA was able to get very high levels of compliance. ODA has done a remarkable job, really emphasizing the importance of Japanese beetle eradication, and people are really on board.

Jessica Rendon: [00:14:38] Yeah, I think roughly like over 98% of people consent every year. The people in this area are incredible to work with and to communicate with. They have a lot of great questions, and they want to know what we're doing and what we're using, and so I'm really impressed that they want to know, and they don't just sign a paper; they really want to be engaged and know the situation. So that's great.

Andony Melathopoulos: [00:15:05] Okay. Let's take a quick break. I have a set of questions to ask all my guests. I am looking forward to a fellow steering committee, Oregon Bee Project members answers. So we'll be right back in just a second.

Okay, we are back. I am so curious what your pollinator book recommendations is going to be.

Jessica Rendon: [00:15:27] Okay, so for pollinator book, I'm sure someone has already mentioned it, but I'd have to go with The Bees in Your Backyard: a Guide to North America's Bees. It's just an extremely great introductory... well, it's not just introductory, because it really goes into identification of the bee families here in North America, there's great pictures, life biology and history descriptions. So yeah, I'll go with that one for my favorite pollinator book.

Andony Melathopoulos: [00:15:58] It's remarkable. And I was really excited: I got an email from Olivia Messinger Carril; they're going to be releasing The Bees of the Eastern US in March. And she has agreed to come on as a guest at the book launch. So we'll be hearing from Olivia, which is always a delight. But the other thing I think is worth mentioning: those high quality images; people in Oregon are used to those high quality images, because they are on the postcards that we distribute, and all the Oregon Bee Project material.

I think it's worth saying that this comes out of your lab. Your lab is where all this remarkable imaging gets done in Oregon.

Jessica Rendon: [00:16:35] Yeah they do incredible work in the lab. I'm just incredibly impressed.

Andony Melathopoulos: [00:16:43] I remember when we asked... we've had one legislator, Representative Jeff Reardon was on the show and he said his favorite book was the ODA book on bees because it had such great pictures.

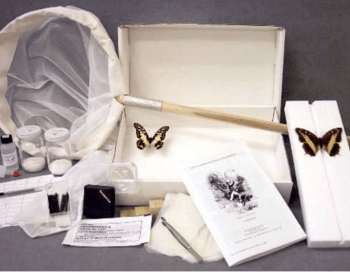

Okay, our next question is what is your go-to tool? When you're doing work with pollinators, what do you absolutely must have?

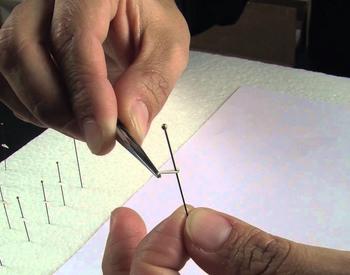

Jessica Rendon: [00:17:04] So this one, I had to say it's my microscopes that my parents got me a couple of years back. They, my mom found a retired entomologist and bought the used microscope from him.

And they drove up all the way from Sacramento, California, up to here, Portland, Oregon cause it was too big to fit in the plane cargo spaces. So they drove all the way up just to bring me this microscope for Christmas. And even though it doesn't have quite the best resolution of some of the microscopes in our lab, it just feels so great to use that microscope from them. Especially, these days; I haven't seen them in so long. Every time I use it, I just feel so connected to them, even though they're far away.

Andony Melathopoulos: [00:17:50] We're saying people who were in the flagship farm program, a lot of those bees you identified, and you've also been a participant in the Bee School, the five day native bee taxonomy course, here at OSU.

Jessica Rendon: [00:18:03] Yeah, I have so thoroughly enjoyed becoming more involved in the bee world; there's so much to learn. There's so many good books and yeah, identifying the flagship farm bees was, I can't even call it work. I could do that all day; it's so fun.

Andony Melathopoulos: [00:18:21] I suppose Jessica, you're the kind of the bee person in your division, like the person people go to when they have bee questions.

Jessica Rendon: [00:18:31] Yeah, by default, I guess. My background is in entomology; I do have a PhD in entomology, but that was in biological control, and so I had a very broad overview of pollinators, but coming into ODA and getting more involved with these programs, I've tried to be a sponge and absorb as much information about pollinators. And I'm learning more every day, and I hope I can better serve Oregon and Oregonians, the more I learn.

Andony Melathopoulos: [00:19:04] You did a great job. I guess our last question is given that you are like the pollinator person at ODA, do you have a favorite pollinator species?

Jessica Rendon: [00:19:14] Yeah, so it was hard to pick one. I was originally going to pick one of our kleptoparasites from Oregon, but I thought I'd go a little more crazier, like really interesting bees from around the world.

There's these bees from South and Central America, the vulture bees. They're also known as like carrion bees. They're in the genus trigona. So as people know, most bees are herbivores; they drink nectar and collect pollen. But these vulture bees, they actually feed off of dead animals. So that's how they get their protein is from the dead animals, not from pollen, from flowers. It's an incredibly rare thing, so I just find that's just so interesting or so unique.

Andony Melathopoulos: [00:20:06] I often think people's choices for these three questions is like a rorschach test on their personality. And I was just like, that is Jessica ...finding the most unique interesting thing.

You're always looking and always bringing up wonderful mysteries to us. I always love getting an email from you.

Jessica Rendon: [00:20:26] Then my final bee is even more crazy and unique. It's a bee from South Africa; I probably won't pronounce it. Rediviva genus; it's in the family melittidae, so in some type of oil collecting bee. And they have the longest arms of any bee. Their forearms are like twice the length of their body. They look like aliens. And I guess that's an adaptation for collecting the oil that's way down inside the flower. So their arms are incredibly long and spindly looking.

I'd highly recommend looking them up.

Andony Melathopoulos: [00:21:09] Wow. That's amazing. Thank you for those Jessica. And thank you so much for giving us a little update on what's going on with Japanese beetle, and let's hope in the next couple of years Japanese beetle is no more in Oregon.

Jessica Rendon: [00:21:22] Yeah, I hope so. That's what we're working towards.

Japanese beetle is a devastating exotic pest. Eradication efforts are underway across the US, including in Oregon. We hear about what is involved with eradication and how it can be done in a way that minimizes impacts to pollinators.

Jessica Rendon is with the Oregon Department of Agriculture’s Insect Pest Prevention and Management Program. She works alongside her fellow entomologists and colleagues to monitor, identify, and eradicate invasive insect species from Oregon. She has had the pleasure of working on the Oregon Bee Project, a cooperative effort between the Oregon Department of Agriculture, the Oregon State University Extension Service, the Oregon Department of Forestry, and a diverse set of stakeholders who are actively engaged in caring for our native and managed bee species. She received a BS degree in Environmental Science from Humboldt State University in 2008, and a PhD in Entomology from the University of Idaho in 2019. The Pacific Northwest holds a special place in her heart.

Book recommendation:

The Bees in Your Backyard: a Guide to North America's Bees by Olivia Messinger Carril

Go-To-Tool:

Microscope

Favorite Pollinator:

- Vulture bees (genus trigona)

- Redivida, South African Long-armed bees