CORVALLIS, Ore. – Legions of lilac lovers look forward to spring when the pink, lavender or white flowers open and send their sweet scent into the air. An unsightly case of lilac blight can turn that excitement to disappointment in no time.

Cool, wet springs favor development of lilac blight, especially if rains follow a late frost or winter injury, according to Jay Pscheidt, Oregon State University Extension plant pathologist.

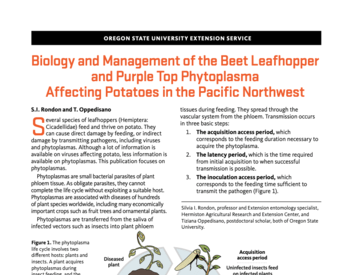

Actually known to scientists by the complete name of "lilac bacterial blight," this disease is caused by the bacteria Pseudomonas syringae pv. syringae. The same organism is the source of bacterial blight on pear, blueberry, cherry, maple and many other woody plants. The symptoms of lilac blight are similar in appearance to fire blight in fruit trees.

At first, leaves look perfectly healthy and then a short time later they look as though someone has placed an open flame near them. Dark black streaks form on one side of young shoots. The flowers wilt and turn brown and unopened flower buds become blackened.

To help avoid lilac blight, don’t fertilize late in the growing season and don’t over fertilize young plants because high nitrogen favors disease development, Pscheidt said. It also helps to space and prune lilac plants so they’re not rubbing against each other and air can circulate freely between plants.

Lilac blight is difficult to control so it’s recommended that you buy blight-resistant varieties whenever you plant new lilacs.

Some species have shown resistance, including S. josikaea, S. komarowii, S. microphylla, S. pekinensis and S. reflexa. Most cultivars of S. vulgaris, which are most commonly grown, are susceptible, but some have been observed with less disease in gardens, including 'Edith Cavell', 'Glory', 'Ludwig Spaeth' and 'Pink Elizabeth.'

If your lilac bush does have infection, prune and burn all infected parts as soon as you notice them. A spray of a copper-based pesticide, which is organic, during the early spring each year should help prevent the problem before the buds begin to break.

Lilac blight bacteria over-winter on diseased twigs or healthy wood. Factors that weaken or injure plants – wounds, frost damage, soil pH, poor or improper nutrition and infection by other pathogens – predispose them to the disease.

Sources of the disease

Sources of this disease can include old cankers, healthy buds, leaf surfaces and nearby weeds and grasses. Wind, rain, insects, tools and infected nursery stock spread the bacteria.

The disease starts as brown spots on stems and leaves of young shoots as they develop in early spring. A yellow halo may also be around the spot. Spots become black and grow rapidly, especially during rainy periods.

On young stems, infection spreads around the stem and girdles it so the shoot bends over at the lesion and the parts above it wither and die. Infections on mature wood occur only on cherry trees, not on lilacs.

Young, infected leaves blacken rapidly starting near the margin and continuing in a wedge-shaped pattern down to the petiole. Eventually the entire leaf dies. On older leaves, spots enlarge slowly. Sometimes, several spots will run together, and the leaf may crinkle at the edge or along the mid-vein. Flower clusters also may be infected and rapidly blighted and blackened. Buds may fail to open or may turn black and die shortly after opening. Symptoms are similar to those of winter injury or drought damage.

To see photos of this disease, visit OSU Extension's "PNW Plant Disease Management Handbook."