Introduction

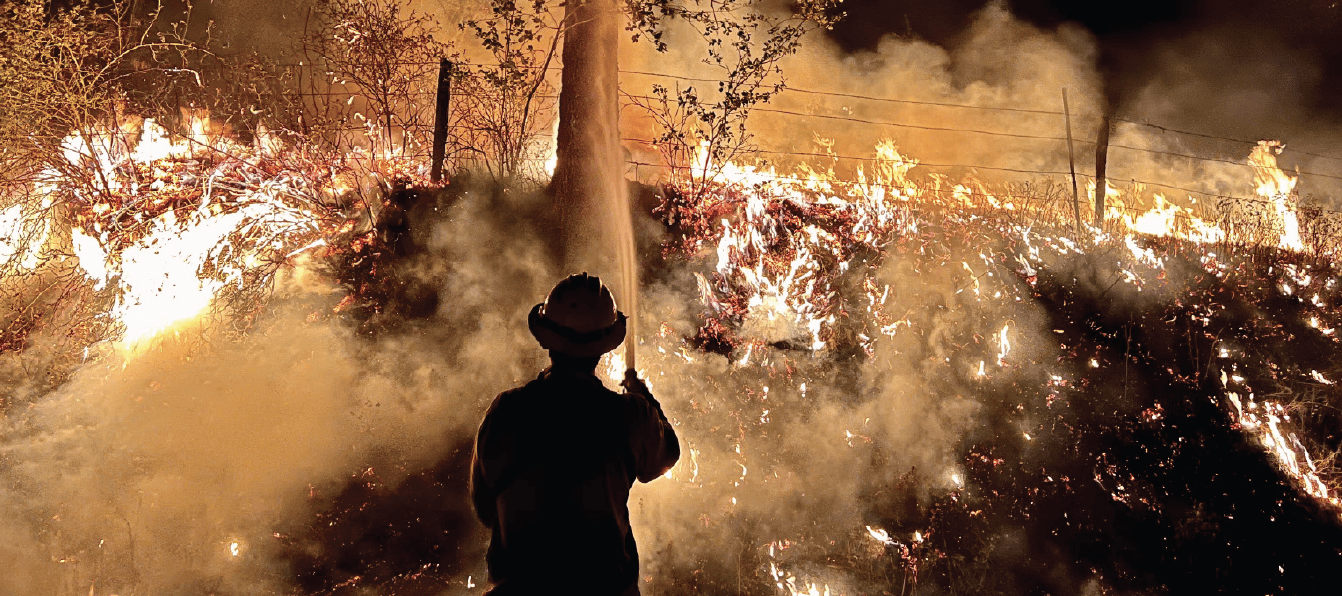

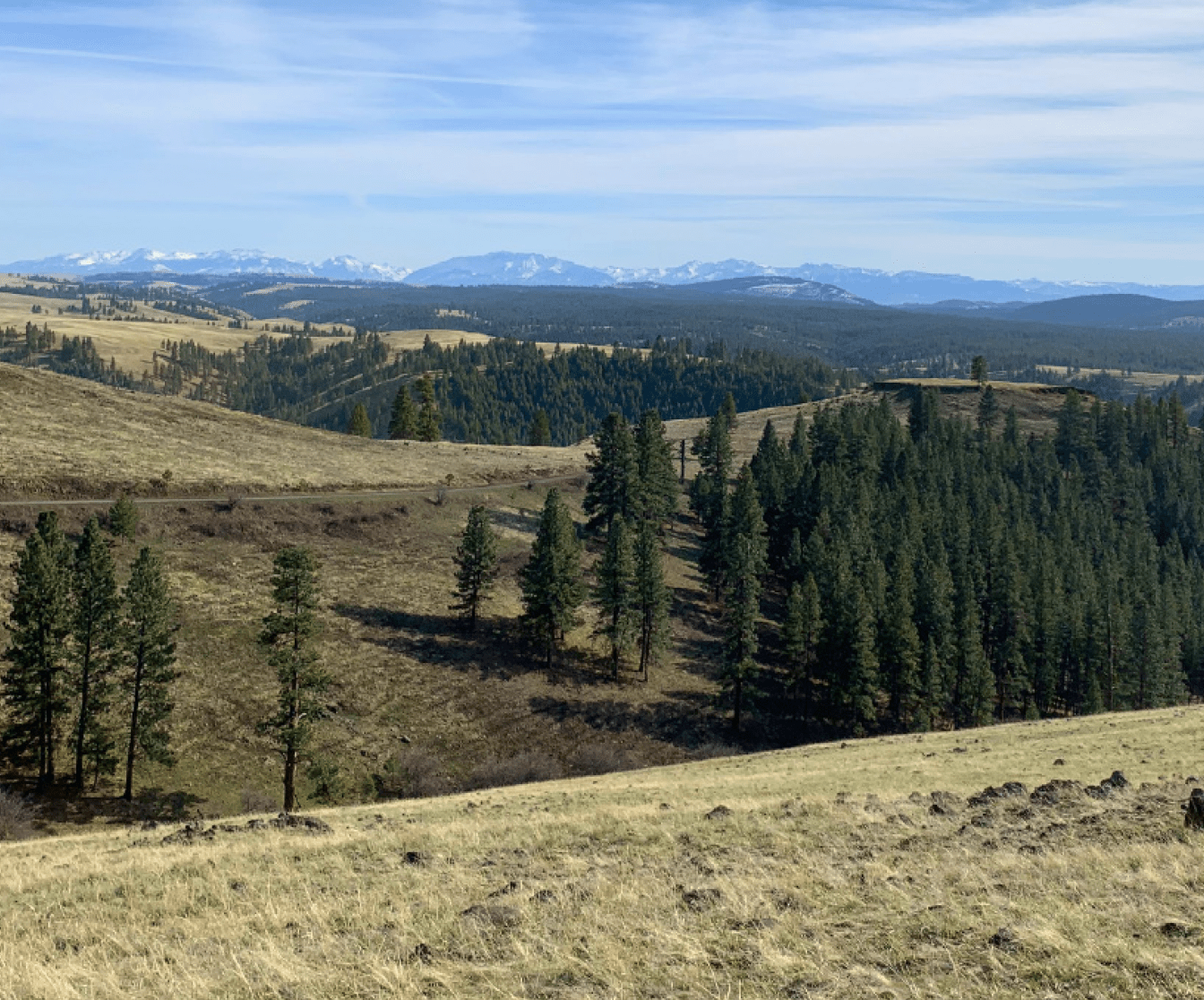

Wildfires are naturally occurring and ecologically important events in Wallowa County. Historically, our landscapes were maintained by fires of varying frequency, intensity and extent. Low-elevation forests typically experience frequent, low-intensity fires. At the same time, those at higher elevations were subject to less frequent but potentially more intense fires. Many of these fires arose from lightning strikes, but historically native populations used fire as a land management tool. For the past 100 or more years, the emphasis in our landscape has focused on fire suppression — and we’ve been very effective. A combination of factors now challenges our collective capacity to control wildfire. Fire suppression has changed our forests; we’re experiencing hotter summers and longer fire seasons; and our farms, homes, recreation areas and other valued investments are intermixed with forests and grasslands, placing them at greater fire risk. Firefighters, land managers and government officials in Wallowa County remain committed to safe and effective fire management, but we all need to pitch in to reduce our collective risk. This isn’t just a job for public agencies and fire departments. There are important roles you can play as a homeowner or other member of the Wallowa County community.

Contents

- Fire in Wallowa County

- Your home and defensible space

- Home hardening: Create an ember-resistant structure

- Your forest

- Some thinning options, illustrated

- Before and after thinning: real-life examples

- Your neighborhood

- Your preparedness plan

- Green - Level 1 evacuation: Get ready

- Yellow level 2 evacuation: Be set

- Level 3 evacuation: Go!

- Our county preparedness

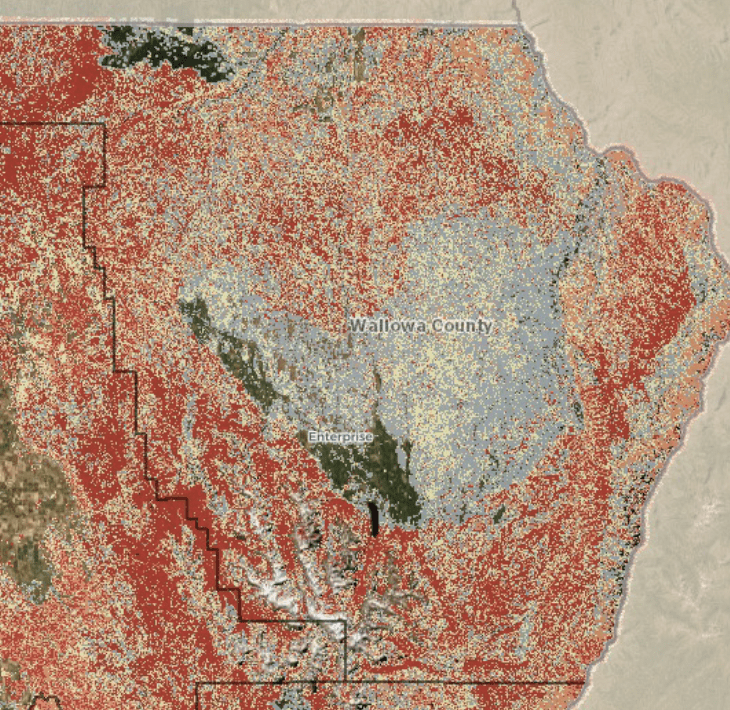

Fire in Wallowa County

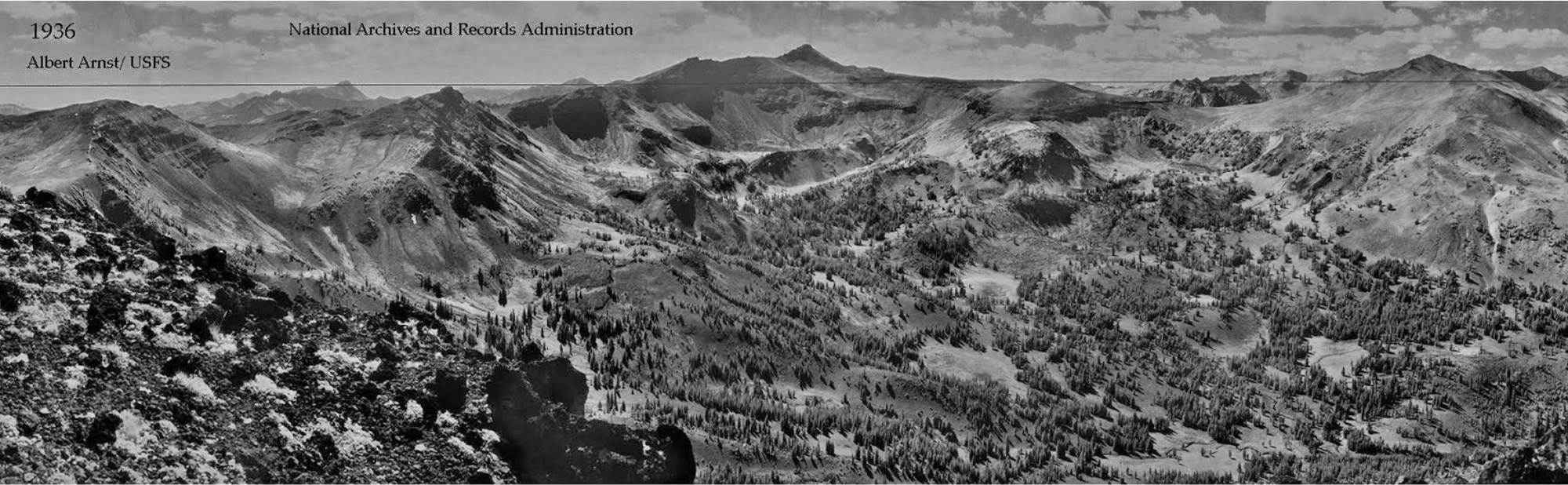

Decades of effective fire suppression and past forest management and grazing practices have changed Wallowa County’s forests, allowing them to become denser (more trees per acre) and more uniform (with fewer patches and gaps across the landscape). They are also much more heavily dominated by shade-tolerant species such as grand or white fir and Douglas-fir that serve as ladder fuels — increasing the likelihood of crown fire. The result is a dramatically increased risk of large, intense wildfires — placing our forests, wildlife habitats, cultural resources, homes and human lives in danger.

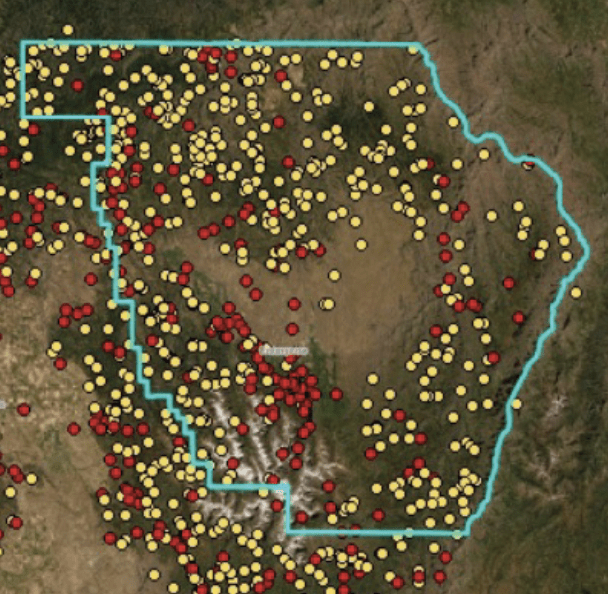

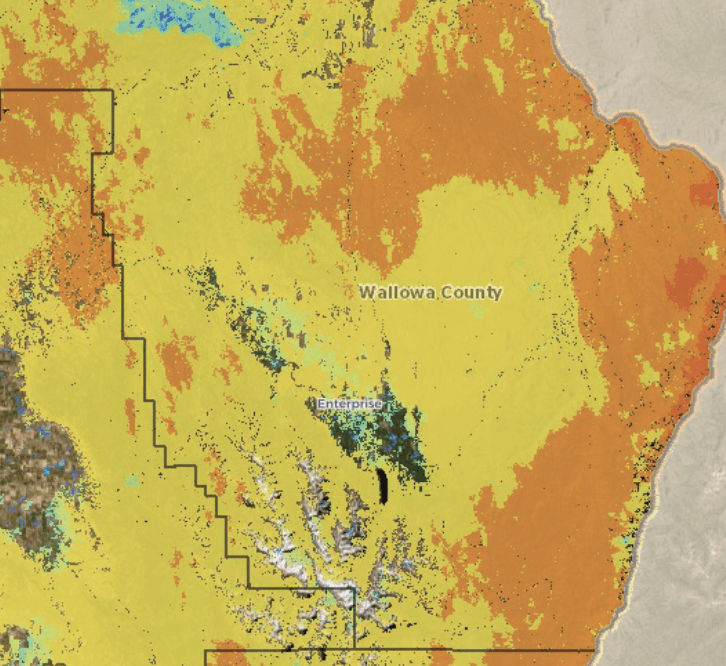

These photos provide compelling evidence of these changes, showing how forests have changed and how our homes and infrastructure have complicated the firefighting environment. The maps (right) convey our current situation — we live where fire starts are common and in environments now at heightened risk of intense fire. It will take collective action to address this situation, making our homes and home landscapes more resistant to fire, reducing fuel loads and fuel continuity in our forests, and strategically locating firebreaks within larger forested areas.

Your home and defensible space

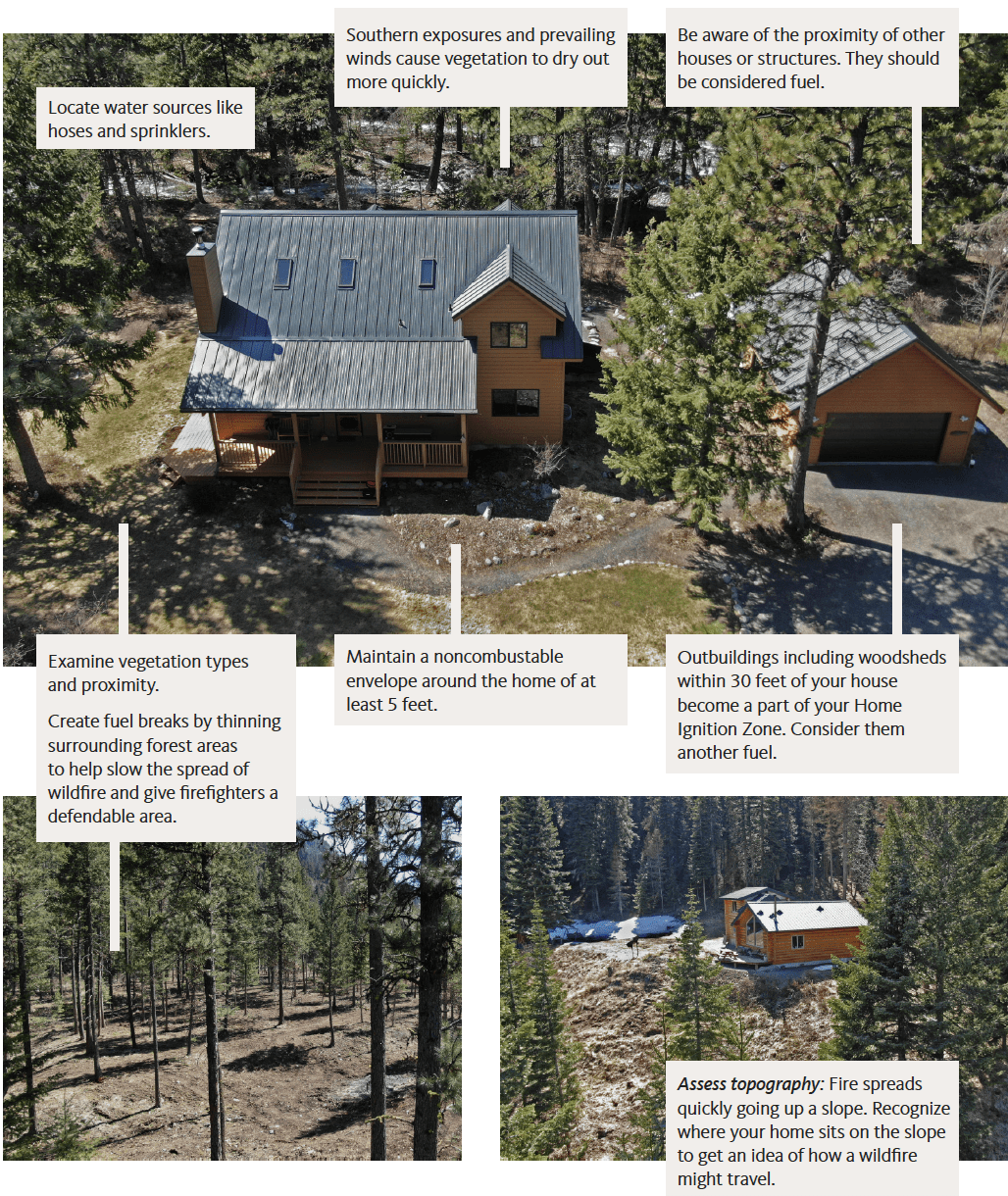

Evaluating your home's ignition zones and the overall landscape

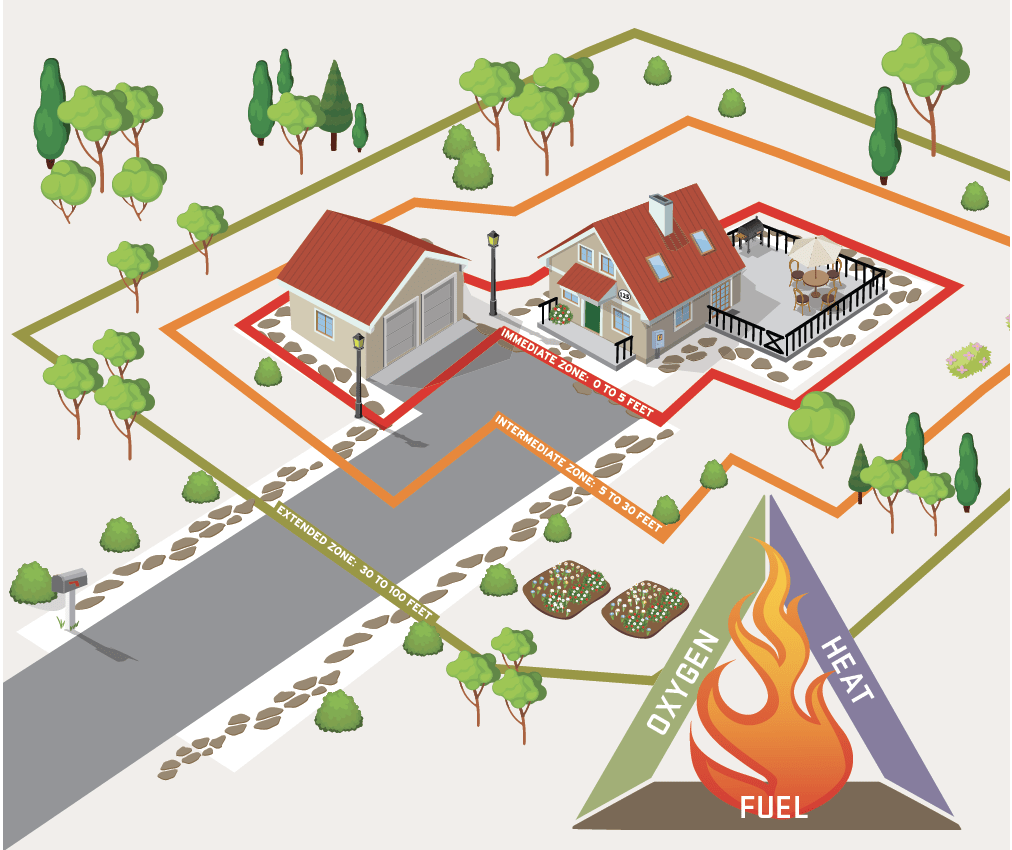

Most homes that burn do so because of flying embers, not from the main front of a wildfire. Embers can travel far ahead of an advancing wildfire. If they land in leaves in a roof gutter or on a patio chair pad, they can quickly ignite and spread to the rest of the home. The photo on the right shows a house from Colorado's 2002 Missionary Ridge Fire. Flying embers ignited fine fuels on the ground. The fire spread to the deck and house — even as the forest around it did not burn. Like the forests and plants around it, your home is fuel for a wildfire. Studies by the U.S. Forest Service and the Insurance Institute for Business and Home Safety have shown that a well-prepared and clean Home Ignition Zone can drastically increase the survivability of your home in the event of a wildfire.

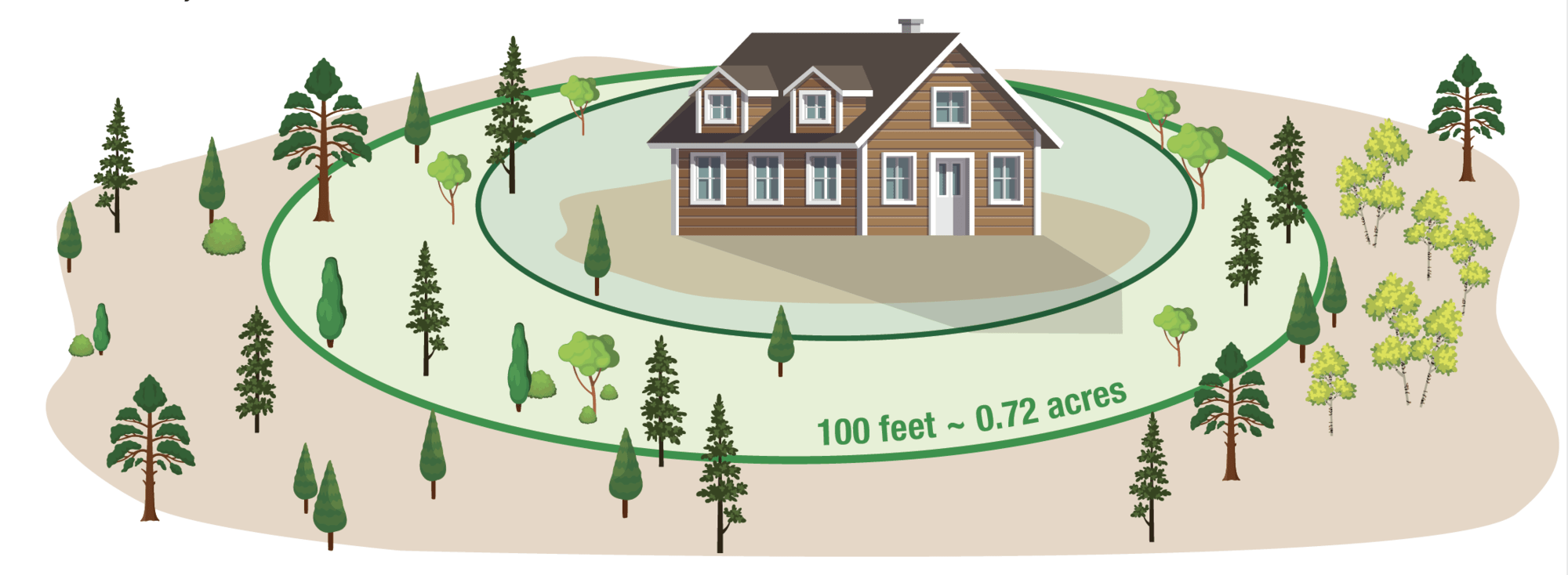

The Home Ignition Zone, or HIZ, is defined as the home and its immediate surroundings, out to a distance of 100 feet (or 200 feet on steeper slopes). The condition of your HIZ is the primary factor determining whether your home will survive a wildfire. The good news is that there is much you can do to reduce your risk! How your home is constructed — including site location, design and building materials — helps determine whether your home will survive a wildfire. In addition to what is located near the house, periodic maintenance, annual clean up and vegetation thinning around the home site also affect the ignitability. Because radiant heat is a big factor in the spread of a fire, potential fuels need to be well separated from one another. This all ultimately defines your HIZ.

Fire requires three ingredients — fuel, heat and oxygen. Without any one of these elements, fire will not occur. While it is difficult to remove heat or oxygen to stop the progress of a wildfire, we can reduce the availability of fuel. This can reduce your home’s ignition potential from embers and increase your home’s likelihood of survival.

Within each zone there are several checklist items that homeowners can and should address before fire season to help protect their property from wildfire.

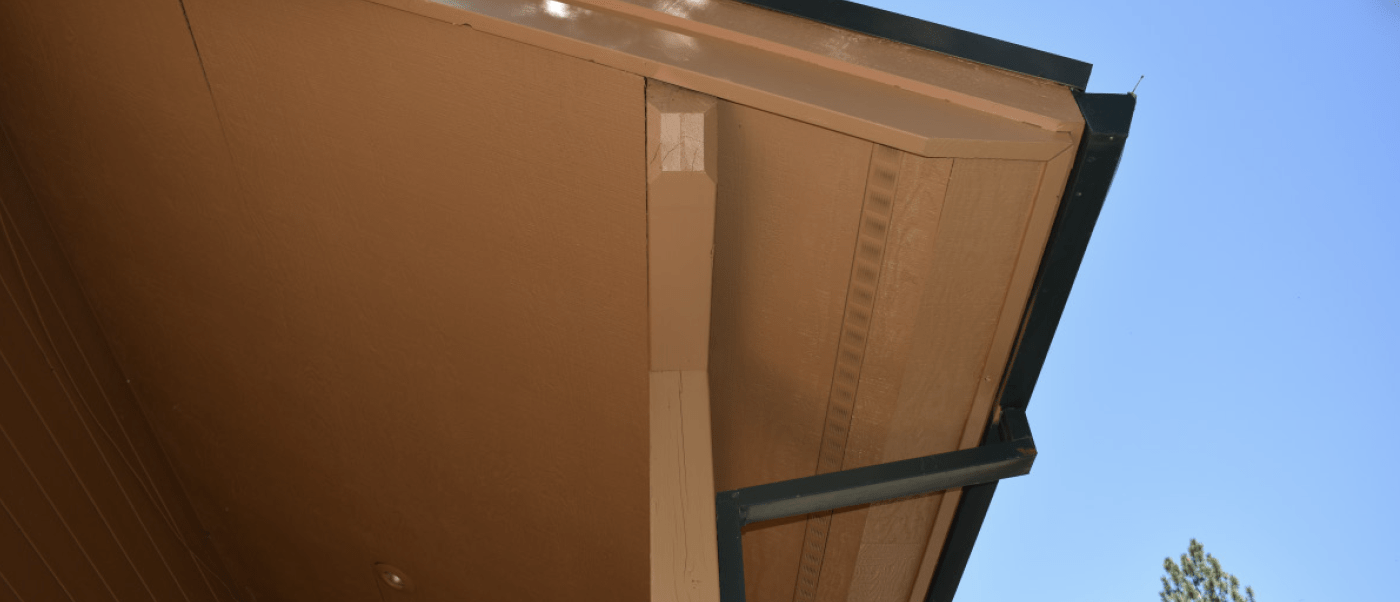

Home hardening: Create an ember-resistant structure

Evaluate roofing materials and assembly. Embers can accumulate under open eaves. Cover the underside with a soffit, box them in or fill gaps with caulk. Install and maintain noncombustable roof gutters. Keep them free of litter and debris.

Check your roof annually to make sure shingles are in good condition — flat, with no tears or gaps. Install firesafe roof materials. Ensure all areas where roof and siding meet are properly flashed. Inspect seams around skylights, chimneys and stovepipes.

Noncombustible stucco, brick, steel or cement board siding are fire-resistant choices. Maintain log thinking. All attic, eave and foundation vents or crawl space openings should be covered with 1/8-inch or smaller wire mesh to keep embers from being blown inside. Consider closing vent shutters (but do not permanently cover vents).

Check chimneys for flue caps and screening over the opening. Check roof turbine vents for screens. Keep roof skylights free of debris. Use double-pane glass instead of a domed skylight. Install double-pane windows with tempered glass.

Immediate zone (0–5 feet): Maintain a noncombustible area

Create a noncombustible area at least 5 feet wide around the base of your home. This area needs to have a very low potential for ignition from flying embers. Use gravel, rock mulches or hard surfaces such as brick and pavers. Keep this area free of woodpiles, wood mulches and flammable shrubs such as juniper. This area should be maintained annually.

Routinely remove debris such as leaves, pine needles or weeds from patios, decks, porches, balconies and fencing. Keep spaces under decks clean or consider enclosing with 1/8-inch or smaller wire mesh. Keep the area clear of flammable brooms, doormats or cushions. Watch for combustible “paths” (such as a line of wood mulch or a wooden fence line) leading to the home.

Maintain your garage as you would your home and ensure the garage doors are properly sealed. If parking outside, keep vehicles on a clean (nonflammable) surface outside the 5-foot noncombustible area.

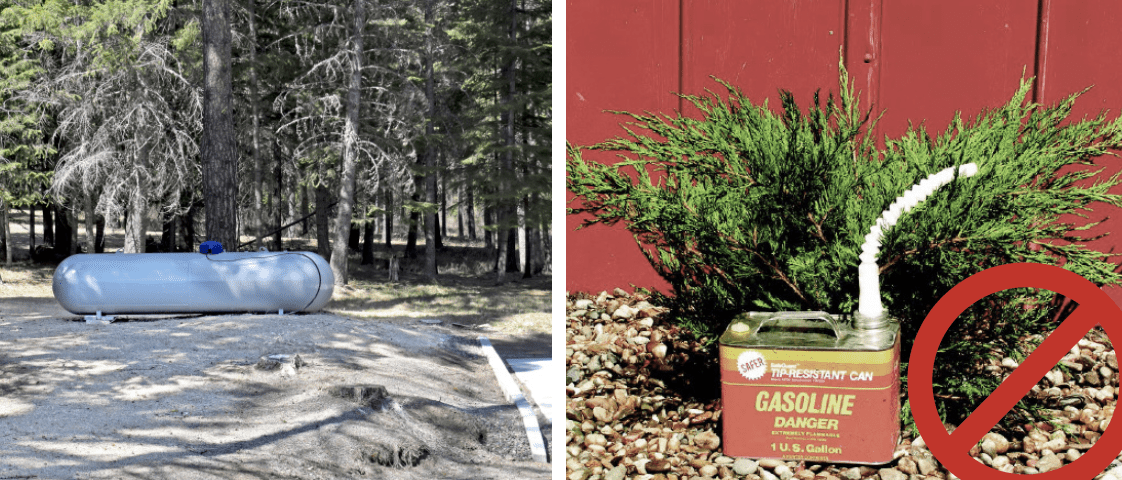

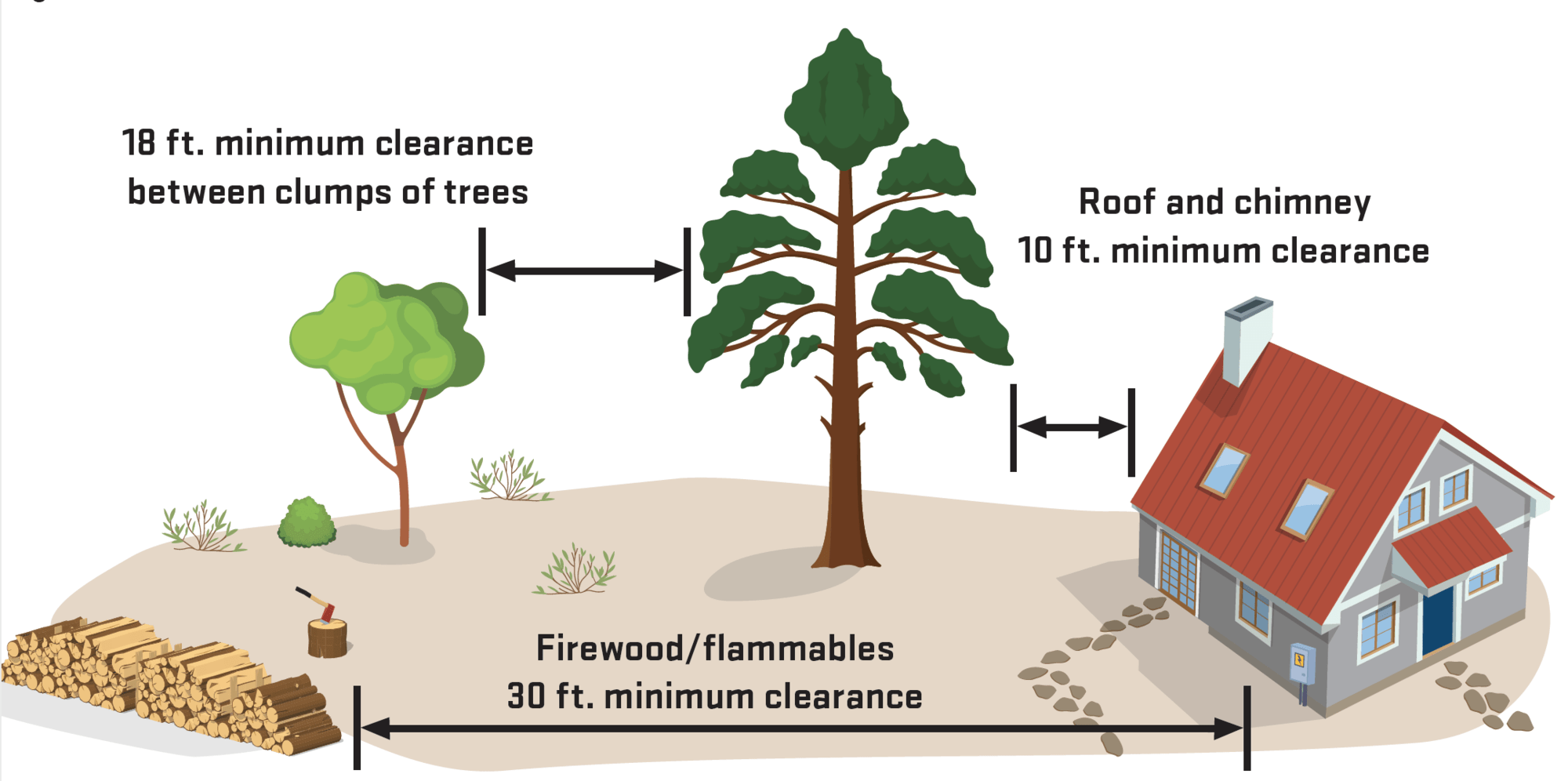

Propane tanks should be kept at least 30 feet from the home and meet local codes. Do not plant ornamental junipers! They contain volatile oils and act as "little gas cans." Ornamental junipers can collect embers, smolder undetected and reignite long after firefighters have left the area.

Intermediate zone (5–30 feet)

The first 30 feet is critical; keep it lean, clean and green:

- Create an area from 5 feet to 30 feet that is fire-resistant and acts as a buffer from embers and flames.

- Clear all flammable vegetation within 10 feet of propane or fuel tanks.

- Keep firewood stacks at least 30 feet from structures and keep covered when possible.

- Remove all dead and dying vegetation in this zone.

- Use low-growing herbaceous vegetation near homes and keep them cultivated and watered. Any dead or dried materials should be removed.

- When retaining native shrubs, reduce their numbers to individual plants or small groups and break up their continuity across the landscape.

- Avoid planting underneath windows, soffit vents, eaves or in front of foundation vents.

- Keep tree limbs pruned at least 10 feet away from your roof, chimney and stovepipe.

- Prune limbs encroaching on power lines (consult professionals first).

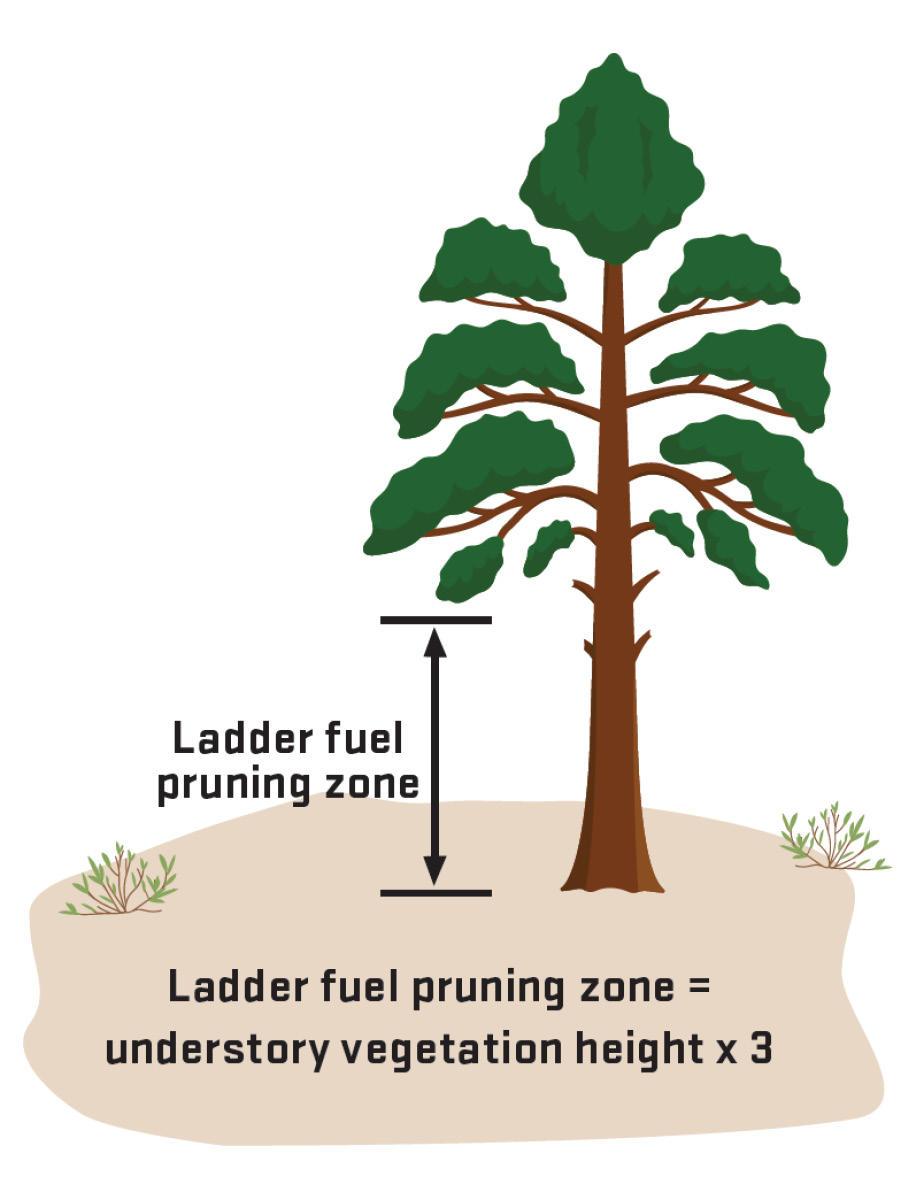

- Prune trees and plants to reduce ladder fuels.

- Keep grasses mowed to 4 inches or less.

- When using mulch, keep it moist and try breaking up its continuity with patches of hardscapes (such as landscape rocks or gravel) or with areas of irrigated grass.

Extended zone (30 feet and beyond): Thin, prune and separate

This area extends from the 30-foot “Lean, Clean and Green” area out to at least 100 feet and up to 200 feet on steeper slopes with thicker vegetation. It usually lies beyond the residential landscape and often consists of naturally occurring plants such as conifer and hardwood trees, brush, forbs and grass. Consider extending this zone on the typical prevailing wind side of the property to ensure protection due to wind-driven wildfire events. If you want to keep a particular small dense clump or patch of trees and shrubs for a visual screen, clear out the area around it, creating an island and ensuring that you are breaking up the continuity of fuels. Do the following on a portion of your Extended Zone each year, treating all of it over time:

- Reduce ladder fuels by pruning low tree branches and shrubs growing directly under trees.

- Remove invasive weeds such as cheatgrass and knapweeds.

- Ensure access routes are properly cleared for safe and effective evacuation.

- Thin dense patches of trees and shrubs to create separation between them to slow the spread of fire.

Properly maintained defensible space can still serve as valuable wildlife habitat!

Key principles for creating your defensible space

The work you do in the Home Ignition Zone is called creating defensible space, and it plays an important role in reducing the risk of losing your home to wildfire. By managing vegetation around your structures, you reduce wildfire threat and allow firefighters to more safely and effectively defend your property. During large wildfire events, it is likely that firefighting resources will be limited for home protection in many neighborhoods. Your defensible space may become your home's best protection.

Know your distance

The size of the defensible space is usually expressed as a distance extending outward from the house in all directions. The recommended distance to treat is a minimum of 100 feet. That distance increases to 200 feet whenever possible or where:

- Slope exceeds 20%.

- Understory vegetation is mostly occupied by shrubs.

- Overstory vegetation is occupied by large-diameter, tall trees.

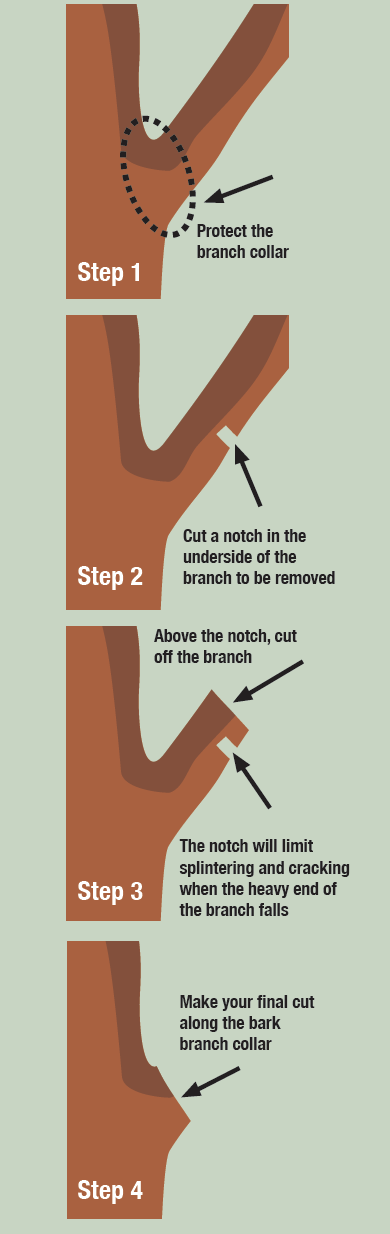

No ladder fuels

Vegetation that can carry fire from surface fuels to taller plants is considered ladder fuel. The goal of ladder fuel reduction or pruning is to create separation that disconnects the tree or plant crowns from the surface vegetation beneath them. Remember, keep a tree’s foliage in the crown and off the ground.

Remove the dead

Within the recommended defensible space zone, remove:

- Dead, dying and suppressed trees

- Dead native and ornamental shrubs

- Dead weeds, grasses and groundcover

- Dead branches on trees, plants and on the ground

Create separation

Dense stands of trees and shrubs pose a significant wildfire threat and contribute to declining tree or plant health and vigor. Thinning to create more space between plants and tree crowns is the best management tool for reducing the wildfire threat around homes and forested properties.

Sensitive areas

If the defensible space zone includes sensitive areas, including lakeshores, a beach, stream-environment zones, scenic resource areas, important wildlife habitats, or conservation or recreation areas, additional considerations may apply. Adequate defensible space can still be achieved with professional advice.

Work with your neighbors

If the defensible space needed around your home exceeds your property boundaries, work with your neighbors to reduce the fuel hazards on their property adjacent to your home.

Wildfires do not recognize property boundaries.

Implementing defensible space practices around every home improves the survivability of entire neighborhoods and works towards creating a fireadapted community.

Contact your local professionals

In Wallowa County, your local Oregon Department of Forestry staff will conduct free home assessments and provide you with guidance on how to protect your home and property from wildfires. Oregon Department of Forestry, Wallowa Unit Office: 541-886-2881.

Additional Resources

Your forest

Reducing fire risk beyond your home landscape

Thinning is the small forestland owner’s best approach to reducing wildfire and forest health risks. By removing some trees, the remaining trees have better access to the site’s water and other resources. This keeps them healthier, and the additional space makes it harder for a fire to spread.

Some thinning recommendations

- To maximize forest health and minimize fire risk in northeastern Oregon forests, preferentially remove grand fir (known locally as white fir) and western/ Rocky Mountain juniper. Preferentially retain (keep) ponderosa pine, western larch and Douglas-fir as they are more resistant to wildfire.

- Use a thinning guide to help you determine how much space to leave between trees. Thinning guides are available as tables, graphs or equations and can be obtained from your local Extension Forester. The equation to the right works well for both ponderosa pine and dry mixed conifer forests in Wallowa County.

- Note that you do not need to achieve “perfect” spacing – use the thinning guides to set your target and then flex it so you can retain healthy trees of fire-resistant species. Some gaps and clumps in your forest will be just fine.

- Plan to thin every 15 to 20 years to keep your Wallowa County forests healthy and fire resilient. More frequent management of seedlings and saplings may be needed to prevent them from becoming ladder fuels.

- If your trees are too small to have commercial value, you may qualify for financial assistance to conduct fuels reduction for forest health improvement. Contact your Oregon Department of Forestry Stewardship Forest to see if your property qualifies.

- Contact OSU Extension Service, your ODF Stewardship Forester, or one of the area’s consulting foresters if you would like additional advice on thinning, forest health or wildfire risk reduction.

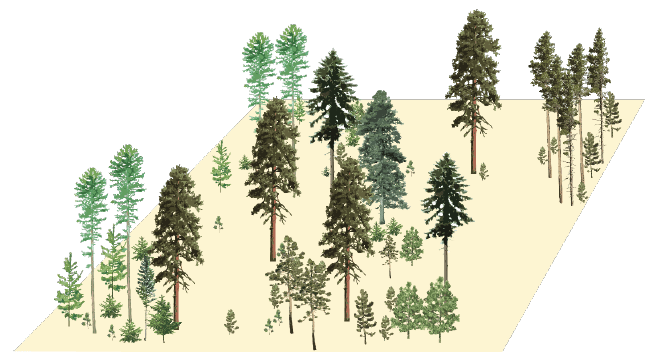

Some thinning options, illustrated

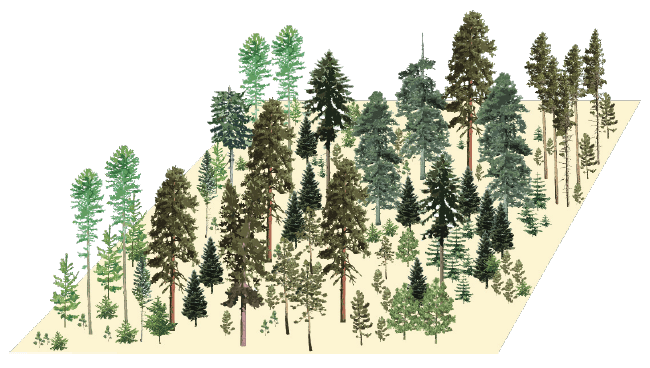

The Unthineed Stand

This unthinned stand has densely packed trees and lots of small trees that could serve as ladder fuels to carry a surface fire into the treetops. Thinning would space out the trees, reducing fire risk and improving the health of the remaining trees.

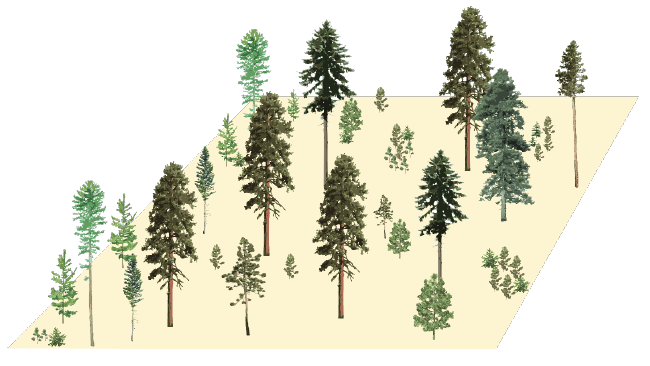

Uniformly Thinned Stand

This uniformly thinned stand gives trees more room to grow and the spacing reduces fire risk. Small trees are spaced away from large trees so they won’t serve as ladder fuels. In this example, the best formed and healthiest trees have been retained, but that doesn't always have to be the case. As the landowner, you get to choose which trees to retain.

Patchy-Clumpy Thinned

Thinning can also incorporate clumps of trees, separated by openings. This arrangement is beneficial for some wildlife species and may be more visually appealing for some landowners. Make sure there is enough space between clumps to keep fire from moving easily between treetops.

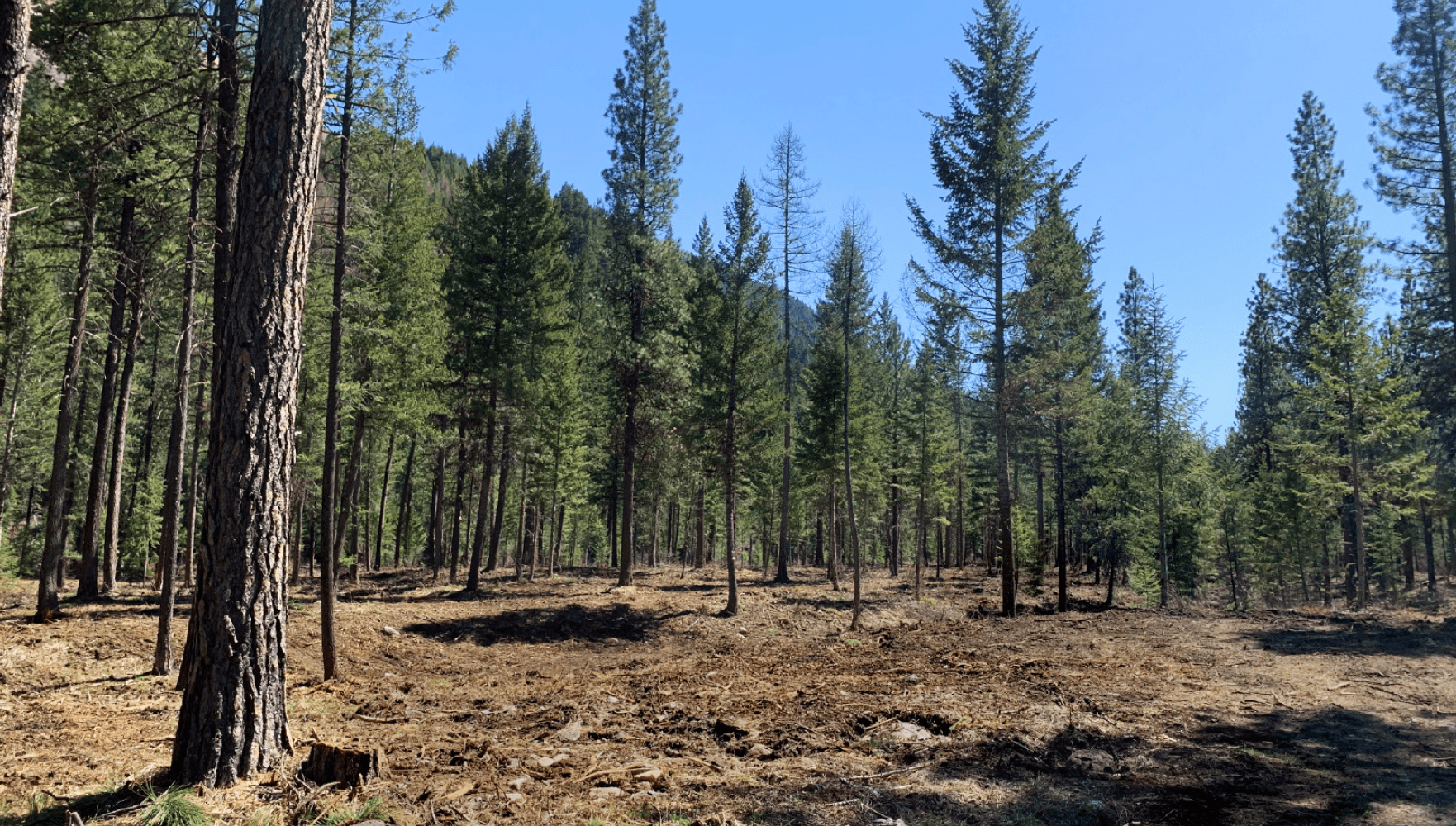

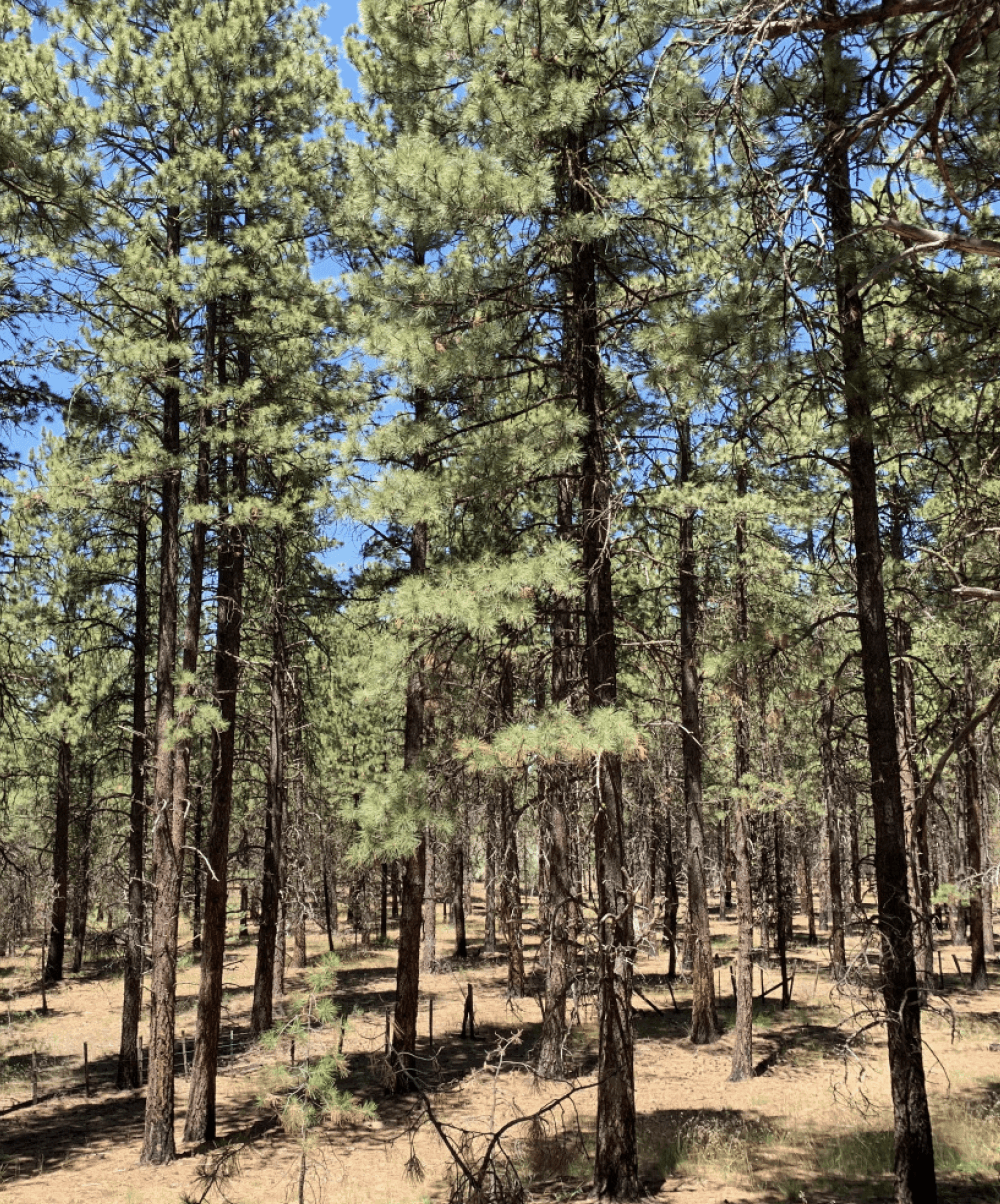

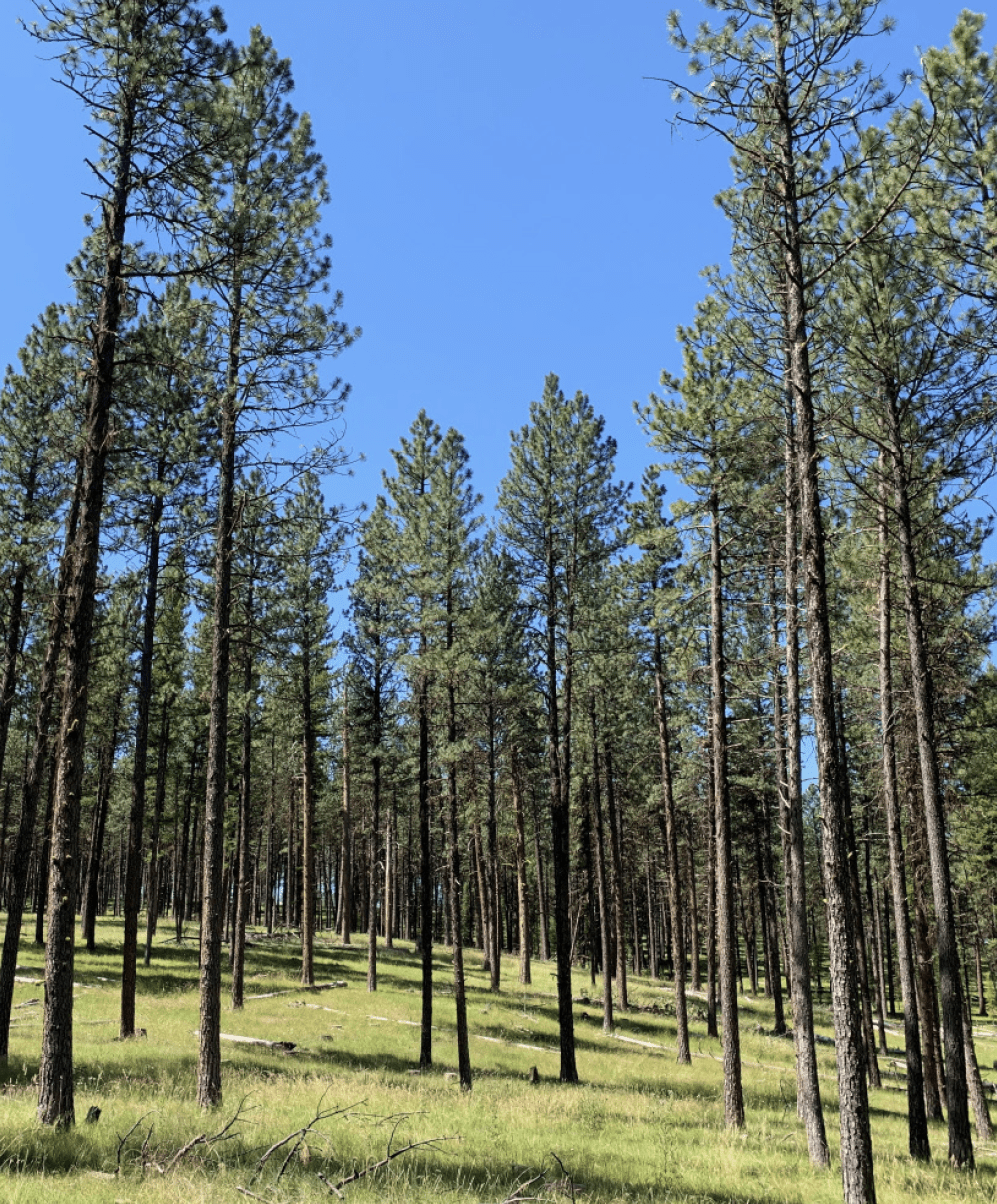

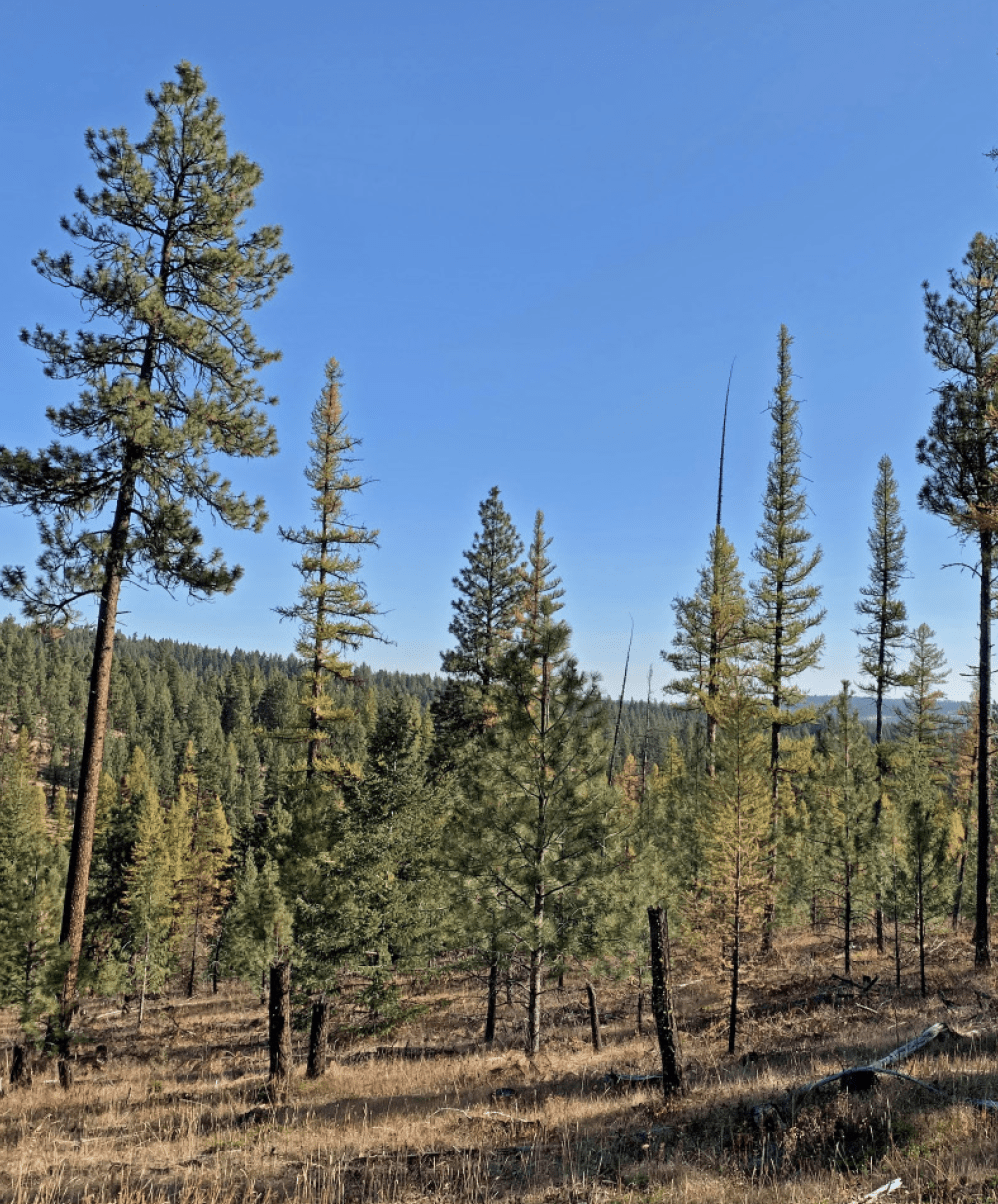

Before and after thinning: real-life examples

*

Manage your slash

Branches, treetops and little trees left on the ground after thinning are called “slash” and can be a significant fire fuel source for many years. Landowners generally pile slash in openings and burn it once it has had some time to dry. Depending on how you thin, you could end up with few large piles or many small piles. Piles are usually partially covered to allow their centers to dry and then burned the following spring or fall. (Make sure you have your ODF burn permit and any required safety equipment.)

Note that slash management is a legal requirement on private forest lands regulated by the Oregon Department of Forestry.

Know the rules

Oregon requires forestland owners or their contractors to file a Notification of Operation with the Oregon Department of Forestry 15 days (or more) in advance of thinning (and a burn permit if burning slash). This can be done online by visiting the Oregon Department of Forestry or by contacting the ODF office.

Your neighborhood

Protecting your community: A Firewise approach

The National Fire Protection Association's Firewise USA™ program provides a model for collective action among neighbors to improve their communities’ fire preparedness. In Firewise communities, neighbors help each other implement and maintain fire risk reduction efforts for their homes and defensible spaces. They cooperate on community-wide efforts such as fuelbreaks, safety zones, emergency access and communication plans.

Fuelbreak

A fuelbreak is a strip of land where highly flammable vegetation is modified to reduce the wildfire threat. Fuelbreaks change fire behavior by slowing it down, reducing the length of flames and preventing the fire from reaching tree canopies. Fuelbreaks can improve the success of fire retardant dropped from the air, provide a safer area for firefighters to operate and allow for easier creation of firelines (a strip of bare ground established during a wildfire). A shaded fuelbreak is created on forested lands when trees are thinned, tree canopies are raised by removing lower branches and the understory vegetation is managed to reduce the fire threat. Community fuelbreaks are particularly effective when integrated with the defensible space of adjacent homes. They can be manmade or naturally occurring (rock outcrops, rivers and meadows).

Emergency access

In order to aid in safe and effective emergency services response to your community during a wildfire event, consider these important aspects. Maintaining safe access will ensure you and your family can evacuate and first responders are able to protect your community.

Address

Your home address should be readily visible from the street. Your address sign should be made of reflective, noncombustible material with characters at least 4 inches high. If your driveway leads to multiple homes, use reflective directional arrows to ensure that responders can quickly find your home.

Safety zone

A safe area is a designated location within a community where people can go to wait out a wildfire. Parks, parking lots, local community centers or fairgrounds may serve as effective safe areas.

Gated driveways

Electronically operated driveway gates require key access for local fire departments and districts. They may require a permit and have additional requirements. Contact your local fire agency prior to installing a gated driveway. Rural, wire gates should have multiple locks for access by fire and medical responders and landowners.

Turnouts

Long, narrow streets and dead ends can deter firefighters and complicate evacuation. Create turnouts in the driveway and access roads that will allow two-way traffic.

Road width and grade

Roads should be at least 20 feet wide and long driveways should be at least 12 feet wide with a steepness grade of less than 12 percent.

Secondary road

When communities only have one way in and out, evacuation of residents while emergency responders are arriving can result in traffic congestion and potentially dangerous driving conditions. A second access road, even one only used for emergency purposes, can improve traffic flow during a wildfire and provide an alternate escape route.

Turnarounds

Homes located at the end of long driveways or dead-end roads should have turnaround areas suitable for large fire equipment. Turnarounds can be a cul-de-sac with at least a 45-foot radius or a location suitable for a 3-point turn. Contact your local fire agency for specific turnaround requirements.

Bridges and culverts

Inadequately built bridges (not capable of safely allowing a loaded fire engine or other heavy machinery) and culverts may prevent firefighting equipment from reaching your home. Be very careful about use of plastic culverts - many are combustible.

Street signs

Street signs should be posted at each intersection leading to your home. Each sign should feature characters that are at least 4 inches high and should be made of reflective, noncombustible material.

Driveway clearance

Remove flammable vegetation extending at least 10 feet from both sides of the driveway. Overhead obstructions (overhanging branches and power lines) should be removed or raised to provide at least a 13½- foot vertical clearance.

Your preparedness plan

Evacuation: Get ready, be set, GO!

Successful community evacuation requires preparation, and it is important to know how to evacuate safely and effectively. Evacuations are conducted to save lives and to allow responding personal to focus on the emergency at hand. Please evacuate promptly when requested.

The evacuation process

Every year, homes in northeast Oregon are threatened by wildfire. The state of Oregon adopted a three-level evacuation process to help families prepare. Officials will determine the areas to be evacuated and the routes to use, depending upon the safest option for the specific incident. If evacuation orders are given, follow directions promptly! You will be advised of potential evacuations as early as possible.

Notification

Effectively communicating emergency information requires partnership between local government, emergency responders, the media and the public.

Although emergency information is made available, YOU must make a conscious effort to seek out that information. No single method of communication is fail-safe during an emergency, so regional public safety officials use a combination of methods to keep the public informed during an emergency. Wildfire conditions may change rapidly. Communication may be obstructed by downed power or phone lines or road closures. Use these resources to stay aware of fire and weather conditions. Consider evacuation based on your local conditions even if you have not been notified to do so.

- Wallowa County Citizen Emergency Notification System

- Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA) – Download app and receive real-time alerts from the National Weather Service

- Local media outlets – Most television and radio stations and newspapers have breaking news on their websites, Facebook pages and Twitter feeds.

Green - Level 1 evacuation: Get ready

Possible evacuation for your area. If you receive a Level 1 warning, preparing for a possible evacuation is important. You may not receive a Level 2 “be set” warning before you are ordered to a Level 3 “go!”

Get ready checklist

Below is a suggested list of things to do and bring in the event you must evacuate. It is important to have everything ready to go, because an evacuation order can come at a moment's notice. If you live in an area of increased wildfire risk it may be crucial you have items, such as a go-kit, prepared in advance.

- Go-kit prepared and accessible

- Several changes of clothes, sturdy shoes (for each household member)

- Essential medications and medical equipment

- Important papers and identification (passport, birth certificate, health information, insurance policies, etc.)

- Important phone numbers, cell phone and charger, computer and backup drive

- Cash, credit cards

- Copies of personal items (such as family photos)

- Leave windows closed

- Park vehicle facing outward in driveway

- Prepare for pet and livestock evacuation

Evacuation plan:

Make sure every household member knows and understands what to do in the event of evacuation. Know where to go, how to get there, and who else knows where you are going. It may be important to make and review this plan before receiving an evacuation notice. Preparedness for people with a disability or functional needs: Anyone with a disability or who lives with, works with, or assists a person with a disability or functional needs should create a plan for an emergency. For some individuals, being notified of or responding to an emergency may be difficult. Addressing these needs ahead of time will reduce the physical and emotional trauma caused by an emergency.

- Be informed of what might happen by learning about community hazards, emergency planning and local warning systems.

- Assess what you will be able to do during an emergency and what you will need help with. Consider creating a personal support network to help you plan and respond to an emergency.

Preparing a go-kit:

The best time to prepare a go-kit is before you need it! Having a go-kit prepared for each family member right now can add to your family’s safety and comfort during and after an emergency. Prepare for at least three days, but preferably seven.

A basic kit should include:

- Water

- One gallon per person, per day

- Stored in unbreakable container and labeled

- Supply of nonperishable packaged or canned foods with hand-operated opener

- Flashlight and extra batteries

- First-aid kit

- Whistle

- Dusk mask (N95 respirator mask suggested)

- Duct tape

- Moist towelettes, garbage bags, plastic ties

- Fire extinguisher

- Sleeping bag or blanket for each person

- Local map, paper and pencil

Preparing pets and livestock for evacuation:

Pets, livestock and other animals may sense impending disasters before humans recognize a threat. Survival instincts can make normal handling techniques ineffective. It is important to prepare in advance for handling animals in these situations. Plan ahead – know where pets, livestock and animals are, and where you will take or leave them. Make truck and trailer arrangements and know evacuation routes. And remember, defensible space around barns and pastures is just as important as around your home.

- Pet preparedness kit:

- Pet carrier, leash and collars with identification

- Vaccination, medical records, vet contact, current photo

- Pet food, water and supplies for 3+ days

- Livestock preparedness kit:

- First aid, hay, feed, water for 3+ days

- Tack, leads and halters

- Wire cutters, sharp knife, shovel, hose and bucket

- Vaccines, medical records, registration, photos

- If animals must be left, leave them in cleared area with food and water for 3+ days

Yellow level 2 evacuation: Be set

Short notice evacuation likely of your area. Monitor public safety, news sites and emergency notifications for information as you prepare for evacuation at any moment. Conditions can change suddenly, so finish preparations for sudden evacuation.

Don’t wait to be asked to leave! Early evacuation, especially with pets and livestock, is a good course of action.

Be set checklists (as time allows)

Prepare to evacuate:

- Be aware of your surroundings. Monitor current fire conditions and weather. Local infrastructure may be down.

- Wear long pants, long sleeves and a jacket made of cotton or wool. Pack hats, gloves and boots.

- Double-check keys, go-kits, pets, livestock preparation.

Inside your home:

- Close all interior doors.

- Leave a light on in each room.

- Remove curtains and anything flammable from around windows.

- Close windows, skylights and exterior doors.

- Turn off pilot lights.

- Close fireplace/stove damper.

Outside your home and outbuildings:

- Double-check intermediate Home Ignition Zone.

- Lock doors.

- Leave gates unlocked.

- Turn on outside lights.

- If you have an emergency water source, post “WATER SOURCE HERE.”

Level 3 evacuation: Go!

Evacuate immediately from your area.

When a wildfire threatens it will likely be dark, smoky, windy, dry and hot. There may be embers being blown about, no power, no phone service and poor water pressure. Remember, there is nothing you own worth your life!

If you receive a Level 3 Evacuation notice, please evacuate immediately – don’t be caught in traffic or by the fire itself!

Evacuating

- Load up and go!

- Close garage door.

- Drive cautiously with headlights on.

- Follow practiced evacuation routes to the designated safe meeting place.

- Follow instructions of emergency responders.

- Let authorities know of anyone needing assistance.

- Be sure to let contacts know when you are safe.

If you cannot leave:

- Stay in your home.

- Call 911.

- Turn on all exterior lights.

- Stay away from windows.

- Drink plenty of water.

- Fill sinks, tubs with water.

- Place wet rags under doors and other openings.

- Do not attempt to leave until after fire has passed.

- After fire passes, check for small fires inside and out. Returning home – after the fire

If your property has been affected by wildfire, use this checklist to chart a course forward and modify to suit your needs.

On the way back to your home:

- Check with law enforcement for an end to evacuation and the all-clear to return.

- Refer to TripCheck for road clearances.

- Look for downed trees, shrubs and rocks loosened by the fire that could create obstacles or fall on to the road or driveway.

- Be aware of standing trees or utility poles by the side of the road that may or may not looked burned, or partially burned. These can be loosened by the fire.

- Watch out for downed power lines.

Once back on your property:

- Wear personal protective equipment:

- Thick boots

- Heavy gloves

- Mask

- Eye protection

- Check around the house for embers in gutters, under decks, wood/debris piles, roof valleys, and shrubs/ vegetation clumps. Check for wisps or smell of smoke.

- Call 911 if any heat found.

- Check for structural damage to the house (foundation cracks, support beams charred).

- Check for gas (smell of gas) and water leaks.

- Check the main power meter (normally outside). If turned off or no power, call the utility service provider

- Make sure pump house/well is in good working order.

- If a visual inspection indicates there was loss of water pressure, or the water system has been damaged, it is likely your water may be contaminated. Do not use water for drinking or cooking until you can have it tested for bacteria.

-

If you notice any damage to gas lines, phone lines, power lines, stay clear and call utility service provider.

Going in the house:

- Before turning on any lights, enter cautiously with a flashlight.

- Look for embers (in the dark) or heat throughout the house, especially in the attic. Smell and look for smoke.

- Check for structural damage inside the house.

- Check the main circuit box. If turned off, make sure all appliances are off before turning the main circuit breaker back on.

- Check interior water-supply system. Visually check for any damage, signs of leaks or changes in operation.

- Check if your water-supply system maintained positive pressure during the fire by turning on a faucet. If you hear air being released, or water flow is not steady, it is likely the system lost pressure and may be compromised. Do not use water for drinking or cooking until you can have it tested for bacteria.

- Discard all food that’s been exposed to heat, smoke, fumes or soot. If the power has been out, discard food that could be spoiling.

Our county preparedness

In Wallowa County, efforts to reduce wildfire risk are coordinated through a Community Wildfire Protection Plan. The Wallowa County CWPP was developed by the Oregon Department of Forestry, local rural fire departments, Wallowa County Emergency Services, the Bureau of Land Management, U.S. Forest Service, private landowners, the Blue Mountain Cohesive Wildfire Strategy Team and other cooperators. A working group meets regularly to update objectives and task lists, identify new needs and priorities, and keep work on track. This approach helps partners focus efforts, work together to find funding and other resources, conduct community outreach and get the most risk reduction for our collective investment.

The CWPP has three goals:

- Ensuring we have effective wildfire response capabilities.

- Building partnerships and educating residents so that we can live safely in fire-prone environments.

- Managing forests and other vegetation to be resilient and reduce risk of extreme wildfires.

To achieve these goals, CWPP cooperators have been working to ensure that:

- Firefighters have the equipment and training they need.

- Agencies and partners work together effectively.

- There is effective communication between agencies and the people they serve, before, during and after wildfires.

- Fuels reduction and other work to reduce wildfire risk is being completed.

- We’re doing all we can to reduce human-caused ignitions.

- Our roads, bridges, powerlines and other infrastructures are designed and constructed to withstand wildfire without loss of life and property.

- Homeowners understand risks and are prepared for wildfire.

- Both structural and wildland fire agencies can meet local community needs.

Wallowa County has gone a step further by developing a Smoke Management Community Response Plan, which helps protect residents and visitors from smoke-related health impacts. It also addresses state restrictions associated with the city of Enterprise, which is currently the county’s sole Smoke Sensitive Receptor Area. The plan includes communication and notification systems for residents and guidance on ways communities can reduce impacts of smoke on residents. It recognizes the need to use prescribed fire to reduce the threat of major wildfire events and improve forest health and resiliency, and promotes efforts to increase the health and safety of community members and firefighters. The plan builds upon a well-established history of successful communication and collaboration in the county and provides a framework for efficient and reliable communication to smoke-vulnerable populations.

Our fire-adapted landscape

Long-term restoration through committed partnerships

Northeastern Oregon is a region where fires played a significant historical role. Fires “managed” forest density (trees per acre), forest composition and structure (what plant species dominated and how they were arranged) and ensured variation in forest and range conditions. Restoring our forests and rangelands to resilient conditions requires a landscape approach involving federal, state, tribal and private landowners and managers. (Fire doesn’t recognize land ownership boundaries; it burns where wind, topography and fuel conditions dictate.)

In northeastern Oregon, a broad partnership has formed to implement an all-lands approach to forest restoration and fire risk reduction. Under the auspices of the Northern Blues Restoration Partnership, the U.S. Forest Service (both Wallowa-Whitman and Umatilla National Forests), the Natural Resources Conservation Service, the Oregon Department of Forestry, county government, local industry, and numerous supporting agencies and entities are working together to identify treatment needs and find the funding and expertise to make those treatments happen.

The partnership focuses on thinning and other fuels reduction efforts within and adjacent to the wildland urban interface — the places where private homes and property intermix with forest and range lands. On lands managed by government or tribal agencies, additional focus is placed on developing and maintaining a network of fuel breaks and on protecting or enhancing unique habitats and other resources. Fire managers in our region recognize that we will never have enough funding and firefighting resources to directly and immediately manage every wildfire. By taking preemptive efforts in targeted areas, we can set our landscape up to let fire play a more natural role while minimizing the risk of large, intense fires.

Thinning is one of the most common restoration treatments applied in our region and it comes in lots of forms. It can be done to remove small trees to reduce fire hazard and provide more water for remaining trees, or it can be implemented to remove trees of many sizes to more specifically manage forest composition and structure. Trees large enough to have commercial value may be sold to offset treatment costs or may be left on site as snags or downed wood. Small trees, slash and brush may be scattered on site and allowed to decompose, piled by hand or machine and later burned or ground up/masticated.

Another very important restoration tool is prescribed fire – the intentional use of fire to manage vegetation (that is, fuel). Prescribed fires are planned well in advance and carefully implemented to accomplish ecological and fuels-reduction objectives, balanced with firefighter and public safety. One of the most challenging factors associated with prescribed burns is getting what we call a “burn window” – a day when the conditions all line up to have both the fire and its smoke behave as desired. While you may think of prescribed fire as a tool used by the Forest Service and other “big” land managers, it is equally valuable for managing private lands and reducing overall fire risk.

None of these treatments offers a one-and-done approach. Restoration requires ongoing efforts and recurring treatments to maintain desired forest and range conditions and keep fire risk low. Partners in Wallowa County are committed to long-term efforts.

Acknowledgments

This publication was developed by the Oregon State University Extension Service Forestry & Natural Resources Program, with support and assistance from Wallowa Resources and the Oregon Department of Forestry. Special thanks to Alyssa Cudmore, Nikki Beachy, Kelly Makela, Lisa Mahon, the Firewise Communities in Wallowa County and Wallowa County Emergency Management.

Adapted from:

Fire Adapted Communities: The Next Step in Wildfire Preparedness, UNCE Publication #SP-14-15;

Fire-Adapted Communities: The Next Step in Wildfire Preparedness, EM 9116

Before Wildfire Strikes! A Handbook for Homeowners and Communities in Southwest Oregon, EM 9131. Permissions granted by University of Nevada Cooperative Extension and the OSU authors, respectively.

Trade-name products and services are mentioned as illustrations only. This does not mean that the Oregon State University Extension Service either endorses these products or services or intends to discriminate against products and services not mentioned.