Pinot leaf curl is a physiological disorder of wine grapes. It is characterized by early-season foliar symptoms. It may be caused by nitrogen metabolism disruption in developing shoots.

Pinot leaf curl was reported in Southern Oregon in the spring of 2019 and resurfaced to a lesser degree in the spring of 2020. But pinot leaf curl may be prevalent across Oregon due to its association with extended low temperatures from early shoot elongation through bloom.

Pinot leaf curl symptoms are most severe in the Pinot-family cultivars (for example, pinot noir, pinot blanc, pinot gris and pinot meunier). Growers have also documented pinot leaf curl in syrah, chardonnay, and cabernet sauvignon.

Pinot leaf curl symptoms

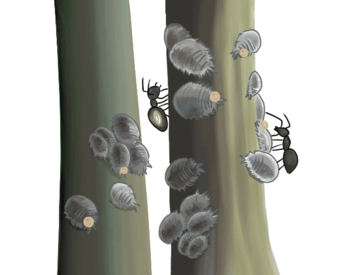

Pinot leaf curl symptoms occur in rapidly expanding tissues, such as shoot tips and unfolding leaves. The symptoms may vary in intensity with the timing and length of early-season low temperatures. Leaf blade curling is a mild symptom. A necrotic region in the central vein on the underside of the leaf (beyond which the blade will curl back towards the shoot) (Figure 1) confirms pinot leaf curl.

Severe symptoms include shoot stunting, partial shoot dieback, petiolar necrosis, leaf necrosis, leaf abscission, cluster loss and “orphaned clusters” (when the shoot tip abscises just above an unaffected cluster) (Figure 2). Persistent low temperatures exacerbate symptoms. Symptom expression may vary widely across clones, cultivars, vineyards and growth stages. For example, symptoms can also be found on growing shoot tips much later in the season (Figure 3).

Cause of pinot leaf curl

Pinot leaf curl and similar disorders (such as false potassium deficiency, also known as “spring fever”) seem related to elevated levels of putrescine, a polyamine derived from remobilized nitrogenous compounds in the roots. Putrescine is associated with cell and tissue death in plants. Arginine is one such source of remobilized nitrogen, which is converted into glutamine for use in early season growth. However, persistent low temperatures and other stressors may help convert arginine into putrescine.

In 2012, California researchers compared amine levels in healthy leaves to leaves with pinot leaf curl symptoms. Glutamine and ammonium levels were similar, but putrescine levels were higher in symptomatic leaves. However, putrescine may not reliably indicate pinot leaf curl. Symptomatic leaves in other vineyards have exhibited the same or even lower putrescine levels compared to asymptomatic leaves. This would suggest a strong interaction of yet-to-be-determined environmental factors.

Elevated foliar putrescine may be correlated with pinot leaf curl, but it is not a consistent cause of the disorder. There is no consistent correlation between leaf putrescine in both symptomatic and asymptomatic leaves with an annual nitrogen fertilizer.

Other causes of pinot leaf curl-like symptoms

Pinot leaf curl has been mistaken for botrytis shoot blight. But Botrytis cinerea fungus flourishes in warm, moist weather. Pinot leaf curl stems from early season cool temperatures. Botrytis primarily infects dead tissues and may occur at the site of pinot leaf curl-associated leaf necrosis. But it does not cause necrosis. Thus, the application of fungicides registered for Botrytis will not reduce the incidence or severity of pinot leaf curl. Additionally, pinot leaf curl is unrelated to grapevine leafroll disease, a viral disease that may cause rolling of leaf margins later in the season.

For more information on other causes of stunted shoot growth in vineyards, see the OSU Extension publication Recognize the Symptoms and Causes of Stunted Growth in Vineyards (EM 8975).

Managing pinot leaf curl

Researchers have no recommended management for pinot leaf curl. They continue to study the disorder. Meanwhile, growers should monitor the incidence and severity of pinot leaf curl symptoms in their vineyards. They can record symptom descriptions and severity, take photos, document the date and duration of symptoms, and collect cultivars, vineyard location and climatic information, such as temperature, growing degree days and precipitation when symptoms appear.

Delayed shoot thinning may allow damaged shoots to recover and aid the selection of shoots to retain. Affected shoots that lose leaves distal to clusters will likely prompt later emergence of lateral shoots at the nodes of the abscised leaves.

Further information

For severe cases of pinot leaf curl, ambiguous symptomology, or concerns related to pinot leaf curl in Oregon, contact Oregon State University Viticulture Extension.

For additional information, please reference the pinot leaf curl review article about Pinot leaf curl published by the California Association of Pest Control Advisers (CAPCA) in collaboration with the University of California Cooperative Extension and UC-Davis and an early report on pinot leaf curl released by the University of California Cooperative Extension Sonoma County.

Literature cited

Adams, D.O., K.E. Franke KE, and L.P. Christensen LP. 1990. Elevated Putrescine Levels in Grapevine Leaves That Display Symptoms of Potassium Deficiency. American Journal of Enology ane Viticulture 41:121-125.