Contents

- Executive summary

- Introduction

- Risk and protective factors for suicide

- Postvention planning

- Limitations

- Conclusion

- References

- Appendix A: Glossary

- Appendix B: Postvention checklist for Extension faculty and staff

- Appendix C: County-level organization worksheet

- Appendix D: Media communications checklist

- Appendix E: Communication Templates

- Appendix F: Community-facing resources

- Appendix G: Internal resources

Executive summary

Suicide, including suicide prevention and postvention, is a complex public health issue. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) defines suicide as death resulting from an individual killing themselves with the intent of dying. According to the CDC, suicide was the 10th-leading cause of death in Oregon in 2021. Furthermore, the CDC noted that Oregon had the 15th-highest annual suicide death rate in the United States, with 19.5 deaths per 100,000 people in 2021.

The Survivors of Suicide Loss Task Force defines postvention as “an organized response in the aftermath of a suicide.” It encompasses a range of activities that include short-term programming and long-term support. Examples of postvention efforts include:

- Educating the public on suicide prevention

- Connecting community members to resources like individual therapy, peer support groups or national hotlines

- Working with the media to ensure safe reporting

- And providing technical assistance.

Other examples of postvention efforts and related resources are listed in Appendix F.

Postvention efforts reduce suicide risk for impacted individuals and communities and can promote healing after a loss. Postvention responses are suicide prevention.

This tool aims to help OSU Extension faculty and staff connect with postvention efforts in their local community in the event of a suicide. This toolkit provides:

- Background on suicide prevention and postvention practices

- Community and policy context behind postvention planning

- A timeline of postvention activities

- Specific factors to consider when tailoring postvention efforts

- Media and safe-reporting practices

- Sample postvention evaluation metrics

- Resources that may be used for your own postvention efforts

According to the Oregon Health Authority, Oregon law mandates that when an individual 24 years or younger kills themself, suicide postvention responses are initiated and coordinated by the local mental health authority. Local mental health authority refers to the board of county commissioners from a county that operates a community mental health program or a tribal council. These suicide postvention responses include a communication protocol and a response protocol. The communication protocol identifies what information must be shared, with whom and when, while the response protocol outlines what people and organizations should be notified or mobilized after a suicide. While there is not currently a legislative mandate for a similar process for suicide deaths of individuals above age 25, some counties have implemented postvention response services for all ages.

In the event of a suicide, OSU Extension may be expected or invited to join this existing postvention response, particularly if staff have program expertise in this area or are impacted directly by the suicide (in the event of the death of a farmer, for example, or a 4-H youth or staff member). This toolkit can provide structure to the postvention response and guide best practices to reduce the possibility of additional harm in the community.

If Extension receives notice of a suicide in the local community from the local mental health authority, review the information provided and follow the instructions included in the notice. Please note: Extension may not receive notice immediately. If Extension becomes aware of a suicide in the community from a third party, contact the applicable county postvention response lead to determine next steps. See the contact list of postvention response leads in Appendix G.

The Deschutes County (OR) Health Services and California Mental Health Services Authority state that shortly after the initial notification, the suicide postvention response team will meet. This team commonly consists of representatives from the local mental health authority, public K-12 schools or universities if applicable and relevant community partners. At this meeting, postvention roles for individuals and organizations will be assigned, protocols reviewed and the next steps determined. If Extension is assigned a role, follow the outlined responsibilities for the specific role as determined in the meeting and follow the response protocol. If Extension is not assigned a role, simply work with the response team and community organizations to provide support as needed. Again, it is possible that Extension may not receive notice at this stage.

The suicide postvention response team will likely meet frequently for the first month. During this time, the team will: determine an outreach strategy; identify people, organizations, and individuals in need of support; identify and track surveillance data; coordinate with the media to ensure safe reporting practices are followed; and work collaboratively with families and the bereaved to safely commemorate the decedent, as outlined by authors Hill and Robinson, as well as the Crook County (OR) Health Department.

About two to three months after the death, the suicide postvention response team will meet to determine intermediate postvention plans. Extension should continue to fulfill its assigned role or provide support as determined by these meetings.

Deschutes County (OR) Health Services and Crook County Health Department note that, in some cases, about nine to 10 months after the death, the suicide postvention response team will meet to determine long-term postvention plans. Extension should continue to fulfill its assigned role. During this meeting, the team will identify how ongoing risk assessment will occur through existing community channels such as workplace or school counseling centers. They will determine what outreach or support services will be available for anniversaries or other significant events or dates, consider ways to build community resilience such as suicide prevention training and complete an evaluation of postvention efforts. Authors Haw and others, agree that media is a powerful tool that can profoundly impact a postvention response. How media report a suicide death can contribute to suicide contagion, otherwise known as the Werther effect, which refers to the increased risk of suicide or suicidal behavior after someone is exposed to suicide, as published by Niederkrotenthaler and group. According to reporting recommendations shared by suicidology.org, safe media reporting minimizes suicide contagion risk by using destigmatizing language, promoting help-seeking behavior and avoiding sensationalizing or romanticizing suicide.

Extension will be “plugging into” a larger postvention response that should include an evaluation component. In practice, this means that Extension faculty and staff will likely be expected to follow a predetermined evaluation plan rather than making an evaluation plan for all postvention programming.

The appendices provide additional resources, including a glossary, checklists and lists of resources.

Introduction

Mental health

According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), “mental health includes our emotional, psychological and social well-being. It affects how we think, feel and act. It also helps determine how we handle stress, relate to others and make healthy choices”.

Poor mental health and mental health conditions are not interchangeable terms. For example, a person can have a poor mental health day and not meet the criteria for a mental health condition. The opposite is true in that a person with a mental health condition can have a good mental health day, as shared by Oregon State University’s Coast to Forest web library.

Research by Andriessen and group has found notable associations between stress and developing mental health conditions and complicated grief. Experiencing a loss by suicide is a psychological stressor that can impact physical and mental health. For example, research has found an association between suicide bereavement after losing a spouse and ischemic heart disease and lung cancer. More broadly, suicide bereavement has also been associated with an increased risk of mental illness, notably depression, anxiety and post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD). Research in collaboration with Veterans Affairs San Diego Healthcare System adds that there is also an increased risk of developing complicated grief, which refers to prolonged bereavement that impairs daily functioning.

Suicide

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention acknowledge the complexity of suicide, including suicide prevention and postvention as a public health issue. Death by suicide refers to when someone kills themselves with the intent of dying. Suicide was the 10th-leading cause of death in Oregon in 2021. As of 2021, Oregon had the 15th-highest annual suicide death rate in the United States, with 19.5 deaths per 100,000 people.

Oregon Suicide Prevention and the Oregon Health Authority indicate some people are more at risk for suicide or suicide attempts than others. In Oregon, men, veterans, youth, older adults, LGBTQ2S+ individuals and American Indians and Alaska Native populations are at higher risk for suicide.

Risk and protective factors for suicide

General risk factors for suicide outlined by the Suicide Prevention Resource Center, National Suicide Prevention Hotline and the American Foundation for Suicide Prevention include:

- History of suicidal behavior or suicide attempts

- Family history of suicide

- History of trauma

- Mental health conditions like depression or substance use disorders

- Suicide exposure

- Access to lethal means

General protective factors outlined by the Suicide Prevention Resource Center, National Suicide Prevention Hotline and the American Foundation for Suicide Prevention include:

- A feeling of connection and belonging

- Access to mental health care and treatment

- Social support from family, friends, community, etc.

- Life skills such as problem-solving skills or coping mechanisms

- Reduced access to lethal means

Suicide prevention

Suicide prevention refers to strategies, programs and services that seek to reduce suicide and suicide attempts, according to the CDC. Suicide prevention strategies include:

- Increasing access to evidence-based mental health treatment:

- Increasing insurance coverage for mental health conditions

- Addressing provider shortages such as community mental health clinics to reach underserved areas and the National Health Service Corps Loan Repayment Program

- Improving coordination of care

- Creating protective environments:

- Reducing access to lethal means like firearms

- Promoting organizational policies and cultures that support positive mental health such as the Together for Life workplace program in Montreal, as shown through research conducted by Mishara

- Promoting connection:

- Increasing social support behaviors such as providing emotional support or connecting people to resources

- Programming and activities that promote community engagement

- Teaching positive coping and problem-solving skills

- Mental health promotion programming

- Parenting and family skills programming

- Finding and supporting individuals at risk:

- Enrolling community members in suicide prevention trainings such as, Applied Suicide Intervention Skills Training (ASIST), Mental Health First Aid (MHFA), Question, Persuade, Refer (QPR)

- Crisis interventions or supports such as hotlines

- Evidence-based treatments such as cognitive behavioral therapy, dialectical behavior therapy

- Decreasing future risk:

- Adhering to safe reporting guidelines for suicide

- Suicide postvention programming and services

- Strengthening economic supports:

- Increasing financial security

- Increasing housing stability

Suicide impact and exposure

Recent studies by A.L. Berman have suggested the number of people exposed to and impacted by suicide is higher than people may expect. For example, you may have heard that at least six people are impacted by one suicide. This number was proposed in the 1970s by Edwin Shneidman and was not evidence-based. Instead, it estimated how many family members were usually eligible for compensation in case of a compensable injury, such as an accidental or work-related death.

In contrast, of those exposed to suicide, Cerel and Feigelman found that the lifetime rates of those who reported feeling significantly impacted by the loss ranged from 20% to 35%. This lifetime rate suggests that the number of people significantly impacted by a suicide loss is much higher than Shneidman’s estimate of “at least six” and can include both family members as well as a variety of community members.

Suicide risk and contagion

Perhaps the most well-known and documented impact of suicide exposure is the subsequent increase in suicide risk and death according to Pitman and Jordan. Work done by Maple and group agrees while the exact risk varies based on various factors, this impact occurs for those who were close to the decedent and those who were not. There is also some evidence that suicide exposure can increase suicidal ideation and behavior. This increased risk of suicide or suicidal behavior is sometimes called suicide contagion, as defined by Haw in 2013. Risk of suicide contagion can be influenced by various factors such as mental health status, age, history of suicidal behavior, proximity and more, as outlined by authors Andriessen and Marshall. According to work conducted by Lahad, there are three main types of proximity:

- Geographic proximity: This refers to the physical distance. Examples of people with close geographic proximity could be eyewitnesses, anyone who discovers the decedent or first responders.

- Social proximity: This refers to the social relationship between an individual and the deceased. Examples of people who may have close social proximity would be family, friends, co-workers and significant others.

- Psychological proximity: This refers to the perceived level of connection between an individual and the decedent. Examples of people with close psychological proximity include people with similar identities or backgrounds to the decedent and those who looked up to the decedent. Youth and young adults can be more impacted in this area, even when there is no social or geographic connection.

Figure 1: Circles of vulnerability model

A suicide cluster is when a social group, geographic area or psychologically related group experiences multiple suicides. As described by Haw and colleagues, clusters can occur in one geographic area or be dispersed but occur in a close time span. Suicide risk can increase in the timeframe after a suicide death and a community postvention response can help to stop any “spreading.”

Suicide risk and media reporting

Media guidelines set forth by Pirkis and others show that sensationalized and stigmatizing media reporting about suicide has been shown to impact suicide risk. This phenomenon is referred to as the Werther effect (or “copycat” behaviors), where people copy or mimic suicidal behavior described in media. Niederkrotenthaler adds, repeated reporting on a singular suicide is associated with increases in suicide rates. In contrast, the Papageno effect, as defined by the Suicide and Crisis Lifeline, suggests that responsible media reporting that includes suicide prevention efforts can have a protective effect. Media reporting guidelines by Reporting on Suicide and the American Association of Suicidology have been created to combat the Werther effect and use the Papageno effect. For more information, see Media and communications.

Suicide bereavement

According to Pitman and others, suicide bereavement refers to the resulting “grief, mourning and adjustment” that follows a death by suicide and can take many forms, including acute, integrated or complicated. Young and group describe acute grief as encompassing strong emotions like anguish, despair or denial that may come in waves soon after a death. For most, this acute grief will shift to integrated grief over time as the bereaved individual adapts to the loss. For some, however, the period of acute grief persists and becomes what is known as complicated grief. Complicated grief refers to bereavement that is prolonged and impairs functioning.

According to Cerel and group, suicide bereavement is a continuum, and differing reactions to a suicide are to be expected. At the broadest level, anyone who knows or knows of someone who died by suicide is "suicide exposed," as described by authors Jordan and McIntosh.

Authors Jordan and McIntosh state that of those who are exposed to suicide, some will fall into the narrower category of “suicide bereaved” which refers to someone “who experiences a high level of self-perceived psychological, physical or social distress for a considerable length of time after exposure to the suicide of another person.” People can be bereaved in the short or long term. Experts in the field identify additional names for the suicide bereaved, including suicide loss survivor, suicide survivor, suicide-bereaved survivors, or bereavement survivor. (See “References” for more information). According to Cerel and group, suicide bereaved was originally used to describe family members, but this definition has since widened to include nonfamily members. This means that those bereaved by suicide may or may not have had a familial or close relationship with the decedent. In this tool, we use the term “suicide bereaved” to avoid confusion with suicide-attempt survivors.

Remember that grief can take many different forms, with the type and intensity of emotions changing frequently, as indicated by Mental Health America.

Stigma

Despite valuable efforts, suicide is still often stigmatized, as described by the Survivors of Suicide Loss Task Force. Multiple researchers suggest that the stigma surrounding suicide can impact help-seeking behaviors and the amount of social support provided. Additionally, the question of whether or not someone “chose” suicide and whether someone’s death was preventable can also impact suicide bereavement. Both of these questions can create a sense of guilt or anger. While these feelings of guilt or anger may occur for some, we want to underscore that grief and its features vary by person, circumstance and culture.

Postvention

The Survivors of Suicide Loss Task Force describe postvention, sometimes called post-suicide intervention, as “an organized response in the aftermath of a suicide.” Postvention encompasses a range of activities. It includes short-term programming, as well as more long-term support. Leading experts in postvention describe examples of postvention efforts that include educating and connecting people to resources, working with the media to ensure safe reporting, providing practical assistance, educating community members on suicide prevention, individual therapy, peer support options or groups, in-person or online, or hotlines.

Research by Campbell and group has shown that having service providers and organizations reach out to people exposed or bereaved by suicide to offer information about support resources significantly decreases the amount of time it takes for people to connect with and receive services. According to authors Szumilas and Kutcher, this means that good postvention matters because it prevents future suicide risk in communities that have experienced a suicide death.

According to the Survivors of Suicide Loss Task Force, postvention is important because it serves three primary purposes

- Assists those exposed to or affected by suicide.

- Decreases the negative impacts of suicide loss.

- Prevents additional suicides.

What does effective suicide postvention look like?

The Survivors of Suicide Loss Task Force also highlights that effective and comprehensive postvention efforts include building a postvention plan or protocol before a suicide occurs. This helps communities respond to a suicide quickly and competently and can help mitigate feelings of chaos or disorganization in a crisis.

According to the Suicide Prevention Resource Center, an effective suicide postvention plan should promote a coordinated, culturally sensitive, trauma-informed community response in which relevant organizations work together to provide support. Some examples of relevant organizations may include emergency medical services, police, coroners or medical examiners, community mental health services, public health agencies and faith-based organizations. The plan should include both immediate short-term responses as well as long-term support, as outlined by the Survivors of Suicide Loss Task Force. Additionally, best practices suggest that the postvention plan should outline safe reporting practices for the media. (See “References”).

In Oregon, each county has a postvention response plan and a postvention response lead.

Remembering self-care

Self-care encompasses practices, activities and environments that support your physical and mental well-being, as described by the National Institute of Mental Health. Being involved in a postvention response can be stressful and emotionally taxing. According to authors Cocker and Joss, this can cause a specific type of stress known as compassion fatigue, a combination of burnout and working with people who have experienced trauma. Remembering to practice self-care is vital. Below are some ways that researchers suggest to support your mental and physical health throughout the postvention process.

- Ways to support your physical health:

- Make sure to eat regularly.

- Stay hydrated.

- Take time to exercise.

- Remember to take any prescription medications.

- Maintain a regular schedule.

- Ways to support your mental health:

- Take breaks.

- Do something you enjoy.

- Do something to relax.

- Connect with friends, coworkers or family.

- Talk to a therapist.

- Ways to support your team’s health:

- Build regular breaks into team meetings.

- Make information about support resources readily available, such as through employee assistance programs.

For additional self-care resources or ideas focused on mental and physical health, see Appendix G. To find a list of mental health resources by county, see Coast to Forest county resources. For additional resources on supporting your team’s health, refer to A Manager's Guide to Suicide Postvention in the Workplace: 10 Action Steps for Dealing with the Aftermath of Suicide.

Postvention planning

After a suicide, a clear protocol to coordinate community responses and ensure that support systems are in place is vital. In Oregon, these postvention protocols exist at the county level and are generally led by the local mental health authority as outlined in state law. This portion of the tool will dive into community postvention plans, including the relevant policy and community context, timeline, media and communication guidelines and evaluation.

Understanding the context

Community context

Postvention planning and implementation is not the sole responsibility of one organization or person. Rather it is a combined effort involving a variety of community stakeholders. Examples of commonly noted stakeholders are:

- Emergency medical services

- Faith-based organizations or leaders

- Funeral directors

- Hospitals

- Law enforcement

- Local government

- Media

- Medical examiners

- Mental health organizations

- Public health agencies or organizations

- Schools and universities

Table 1 provides a more in-depth explanation of community organizations, people and positions that are commonly involved in postvention activities in Oregon.

Table 2 describes the common roles that may be assigned in a suicide postvention response team.

Appendix C includes a county level organization worksheet based on these tables. This worksheet should be completed on a yearly basis by the Family & Community Health colleague in the county. In the absence of a Family & Community Health staff member, the worksheet should be completed by the regional director or local liaison. Completing this worksheet on a yearly basis ensures that Extension has a comprehensive list of people and organizations involved in postvention and streamlines communication.

| Organization or position | Description |

|---|---|

| Community mental health program (CMHP) | An entity focused on mental health that has a contract with the Health Systems Division of the Oregon Health Authority or the local mental health authority (LMHA). A list of community mental health programs can be found via the Oregon Health Authority website. |

| Local mental health authority (LMHA) | LMHA refers to the board of county commissioners from a community mental health program (CMHP) or a tribal council. Sometimes, the LMHA may include two or more boards of county commissioners. LMHAs are responsible for initiating and coordinating postvention responses in the event of youth suicide. Information about who the postvention response lead is for each county can be found in Table 2. |

| Suicide postvention response team (SPRT) | This team coordinates and supports postvention planning, implementation and evaluation. This team is composed of a variety of community stakeholders and organizations. |

| Oregon Health Authority (OHA) | A governmental agency that provides technical assistance to local mental health authorities and community partners for developing and updating Communication and Response Protocols. |

| OHA youth suicide prevention policy coordinator | This individual is responsible for reviewing communication and response protocols annually and providing technical assistance on best practices for these protocols. |

| Designated reporter | An individual selected by the local mental health authority (LMHA) who is responsible for reporting a suspected youth suicide to the OHA youth suicide prevention policy coordinator. |

| Emergency medical services | Emergency medical services may be the first responders to the scene of death and may have early contact with those bereaved by suicide. |

| Law enforcement | Law enforcement is involved in the death investigation process. Law enforcement may also be the first responders to the death scene and have early contact with those bereaved by suicide. |

| Media | Media coverage, including social media, plays an important role in preventing suicide contagion and disseminating postvention support services. Media stakeholders may include local news stations, newspapers or reporters. |

| Medical examiner | A physician who investigates and certifies the cause and manner of death. They are responsible for determining whether a death was a suicide. |

| Community partners | These are organizations or individuals that are involved with or support postvention efforts. Examples of community partners include local government, mental health organizations or services, hospitals, emergency medical services, schools, universities, funeral directors, faith-based organizations or leaders and Extension. |

| Schools and universities | Public K-12 schools, public universities and private post-secondary schools are all required to have a communication protocol and to notify their local mental health authority of any suspected suicides. Schools are also a common community partner involved in postvention. |

Sources: Youth Suicide Communication and Post-Intervention Plan, Services to Be Provided by Community Mental Health Programs, Crook County Health Department Suicide Communication and Response Policy & Protocol, Responding to Grief, Trauma, and Distress After a Suicide: U.S. National Guidelines | National Action Alliance for Suicide Prevention, After a Suicide: A Toolkit for Schools and CDC Recommendations for a Community Plan for the Prevention and Containment of Suicide Clusters.

| Roles | Description |

|---|---|

| Postvention response lead | A designated individual who is responsible for organizing the postvention response based on the response protocol. In most counties this person is also the communication lead. A list of the postvention response leads is available on the Oregon Health Authority youth suicide prevention website. |

| Communication lead | A designated individual who is responsible for centralizing information-sharing activities after a youth suicide. In most counties this person is also the Postvention Response Lead. |

| Therapeutic support mobilization lead | Assembles a team of behavioral health providers to provide evidence-based support, provide relevant resources and work with behavioral health professionals to screen those at risk and provide referrals as needed. |

| Data monitor | Conduct data surveillance of 911 and suicide crisis line calls, ER and Urgent Care visits related to mental health or suicide, and other relevant data sources. |

| Survivor support liaison | Acts as the primary contact and support for family and others bereaved by suicide. Helps link those bereaved by suicide to resources. |

| Social media monitor lead | Assembles a team to monitor social media for potentially risky posts or comments. |

*Please note that except for the postvention response lead, the exact roles and corresponding responsibilities may vary by county and the needs of the given response.

Sources: Crook County Health Department Suicide Communication and Response Policy & Protocol, Deschutes County Health Services Suicide Communication and Response Policy and Protocol and Youth Suicide Communication and Post-Intervention Plan.

Policy context

In Oregon, five different statutes pertain to suicide prevention and postvention, as well as a set of Oregon administrative rules that outline the implementation of these laws.

Regarding prevention, Adi’s Act requires Oregon public school districts K-12 to develop a comprehensive student suicide prevention plan.

Regarding postvention, OAR 309-027, ORS 146.100, and ORS 418.735 direct local mental health authorities (LMHAs) to notify local systems such as public K-12 schools in the event of a youth suicide. The legislation defines “youth” as anyone 24 years old or younger. OAR 309-027 implements SB 561 from 2015, SB 485 from 2019, SB 918 from 2019, and HB3037 from 2021 and provides more specific direction for the communication protocol and postvention response. ORS 146.100, and ORS 418.735 require medical examiners to notify the local mental health authority in the event of a suspected youth suicide and requires the Oregon Health Authority (OHA) to make plans for communication between local mental health authorities. The key takeaways from these rules are:

- Local mental health authorities (LMHAs), in collaboration with community partners, must create a communication protocol that identifies what information must be shared, with whom and when. This plan outlines how the communication lead will be selected and the specific roles of the local mental health authorities (LMHAs) and community partners.

- Local mental health authorities (LMHAs) in collaboration with community partners, must create a response protocol that includes what people and organizations should be notified and mobilized after a youth suicide. This plan includes outlining how a postvention response lead will be selected and the roles and responsibilities of community partners in the postvention response.

- Oregon Health Authority (OHA) will provide technical assistance to support the communication and response protocols.

- Each local mental health authority (LMHA) will be responsible for selecting a designated reporter, who may also be referred to as “561 reporter” or postvention response lead and backup designated reporter who will be responsible for reporting a suspected youth suicide to the Oregon Health Authority (OHA) youth suicide prevention policy coordinator. The local mental health authority (LMHA) also reports postvention activities to the Oregon Health Authority (OHA).

- Each year, the local mental health authority (LMHA) and applicable community partners must complete a review of the communication and response protocols.

- An evaluation process must be identified for community partners to assess each youth suicide response.

Best practices for postvention response

A postvention response should be:

- Trauma-informed: Suicide is a traumatic event. Ensuring that postvention planning and services are trauma-informed is vital. This means that postvention plans and responses must recognize the negative impacts of trauma and seek to “restore a sense of safety, power and self-worth” as described by Trauma Informed Oregon.

- Community-focused: Suicide has community-wide impacts and requires a coordinated, community-focused response.

- Accessible: Postvention services and resources should be accessible. Something is accessible when anyone can use the service or participate. In practice, accessibility should be incorporated throughout the postvention process, from planning to evaluation.

- Culturally sensitive: As noted by the Survivors of Suicide Loss Task Force, suicide postvention should be based in the cultural context of the community and should be accommodating of different cultural norms around bereavement.

- Evidence-based: Postvention planning and services should be based on the best available research and data, such as information provided by the Suicide Prevention Resource Center.

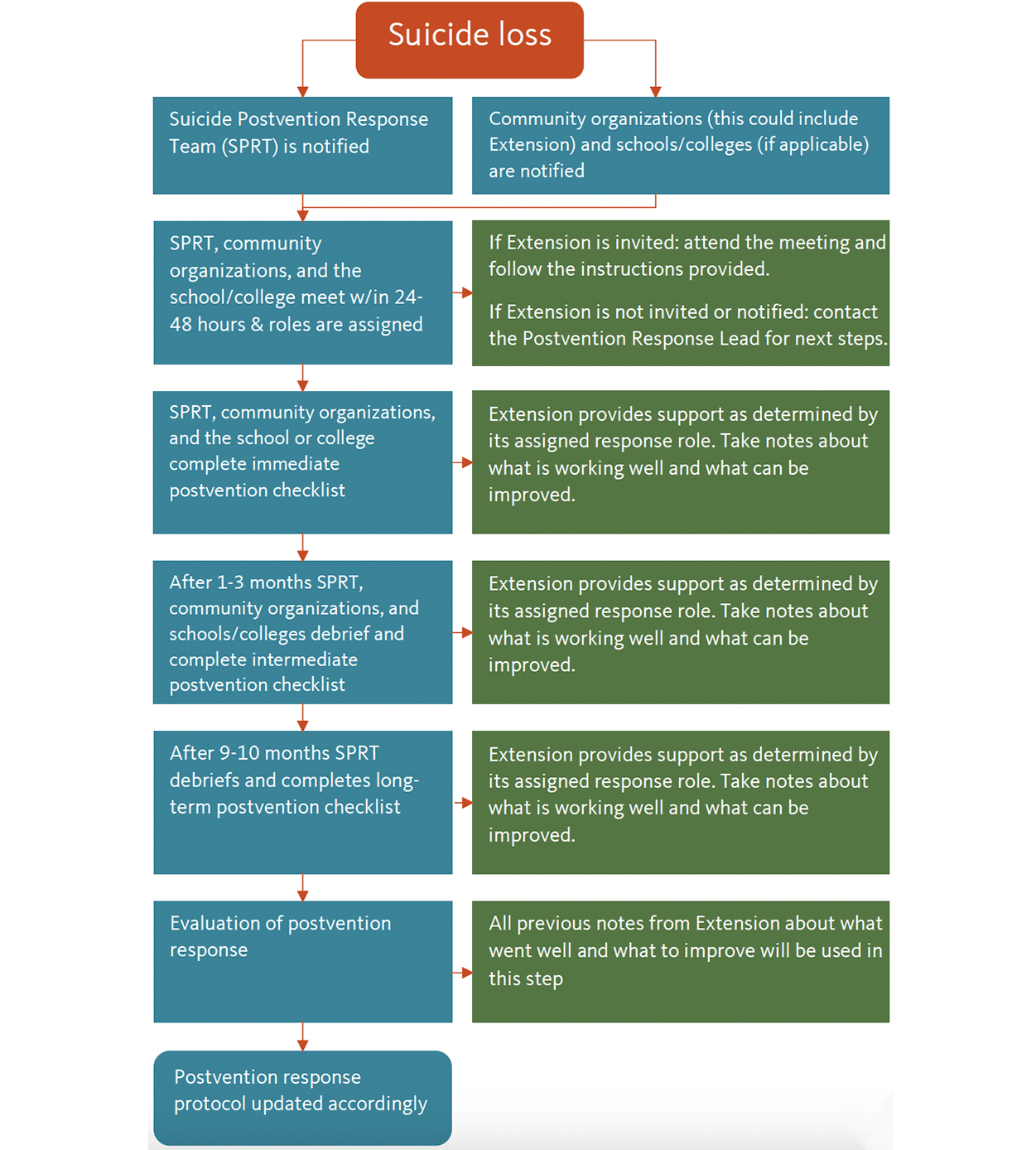

Sample response timeline

The timeline below is meant to give a general overview of postvention steps. Please note, the exact order or timing may vary between communities. The sample timeline is based on the Youth Suicide Communication and Post-Intervention Plan, Crook County Health Department Suicide Communication and Response Policy & Protocol, Deschutes County Health Services Suicide Communication and Response Policy and Protocol, After Rural Suicide, Responding to Suicide Clusters in the Community and Suicide Postvention: Going Beyond Prevention and Intervention. To find out the precise timeline and action steps for your local community, refer to the suicide communication and response protocol for your county. If you do not have access to these protocols, please contact your local mental health authority (LMHA) or suicide prevention coordinator. For ease of access, a checklist version of this timeline is available in Appendix B.

Immediate response

- The person or organization outlined in the county communication protocol will verify the death and document relevant information like name, date of birth, date of death, and other relevant information.

- Following the county communication protocol, the Suicide Postvention Response Team (SPRT), public K-12 school (if applicable), and relevant community organizations will be notified of the death and will meet within 24-48 hours.

- If Extension receives notice at this step:

- Review the information provided and follow the instructions included in the notice. Communicate any additional support needs to the suicide postvention response team (SPRT).

- If Extension does not receive notice at this step:

- Extension may not receive notice at this stage. If Extension becomes aware of a suicide in the community from a third party, contact the applicable county postvention response lead to determine the next steps. A contact list of the postvention response leads can be found in Appendix G.

- If Extension receives notice at this step:

- At this meeting, postvention roles for individuals and organizations will be assigned, postvention protocols will be reviewed, and next steps will be determined.

- If Extension is assigned a role: Follow the outlined responsibilities for the specific role as determined in the meeting and follow the Response Protocol. If additional support is needed by Extension to complete its role, request support through the local mental health authority (LMHA). The bullet points in italics below outline the main responsibilities of each role.

- If Extension is not assigned a role: Work with the Suicide Postvention Response Team and community organizations to provide support as needed. If you have questions or need clarification, it is best to ask before acting. This is because collaboration and communication are essential to ensure that responses are properly coordinated and efforts are not duplicated.

- Communication lead and the communication team:

- Determine the talking points for community-facing communications that respect the wishes of the decedent’s family.

- Please note that even if Extension is not involved with the Communication Team Extension will still be expected to follow these talking points for any communications.

- Coordinate with the media to ensure safe reporting practices are followed.

- Again, even if Extension is not involved with the communication team, Extension must follow safe reporting practices. Please set aside some time to familiarize yourself with the basics of safe reporting as outlined in this tool’s “Media and communications” section.

- Determine the talking points for community-facing communications that respect the wishes of the decedent’s family.

- Social media monitor lead and social media monitoring team:

- Monitor social media (e.g., Facebook, Instagram, TikTok) for possible harmful content and identify individuals impacted or at risk of suicide.

- Make a template response to social media posts and comments.

- Therapeutic support mobilization lead and team:

- Identify clinicians and organizations that will provide therapeutic support. Determine if there is a need for a behavioral health crisis support team.

- Identify people and organizations who may need therapeutic support.

- Data monitor:

- Identify what data sources to track and how often surveillance updates will be sent to the suicide postvention response team.

- Suicide prevention coordinator or suicide postvention response team lead:

- Within seven days, make an initial outreach call to offer resources to those bereaved by suicide and to any organizations that the decedent was connected to as outlined in OAR 309-027 and ORS 418.735.

- Survivor support liaison:

- Determine what outreach strategy should be used to connect with people needing support.

- Work collaboratively with families and the bereaved to safely commemorate the decedent.

- During the immediate response period, the suicide postvention response team, public K-12 school (if applicable) and community organizations will likely meet frequently (daily or every other day).

- If invited, Extension should attend these meetings. If Extension is invited but unable to attend, then Extension should read the meeting minutes to stay up to date.

- At the end of the immediate response phase, the suicide postvention response team, public K-12 schools (if applicable), and community organizations will debrief and discuss what went well and what to improve.

- Throughout this phase, Extension should communicate any emerging needs to the postvention response lead. Additionally, Extension should be taking notes about what is going well, any issues that may arise, and any ideas for improving the response. For guidance on what to include in these notes, please refer to the Evaluation section of this tool.

Intermediate response (2-3 months)

- In most cases, about 2-3 months after the death, the suicide postvention response team (SPRT), public K-12 school (if applicable) and community organizations will meet to determine intermediate postvention plans.

- Extension should continue to fulfill its assigned role and/or provide support as determined by these meetings. If additional support is needed by Extension to complete its role, request support through the local mental health authority (LMHA).

- If Extension has not been involved in the postvention response prior to this point: Extension may not have received notice prior to this stage. If Extension becomes aware of a suicide in the community from a third party or if Extension is contacted by a third party to provide support, contact the applicable county postvention response lead to determine next steps.

- Therapeutic support mobilization lead and team or survivors support liaison: Continue to identify those in need of support.

- Survivor support liaison:

- Continue to provide support and resources for those bereaved by suicide and identify any additional resources that may be helpful.

- Provide an update on those bereaved by suicide, including any family members of the decedent.

- Communication lead and the communication team: Continue to coordinate with the media as needed.

- Social media monitor: Continue to monitor social media.

- Data monitor: Review surveillance data to determine if additional support or programming are needed.

- During the intermediate response period, the suicide postvention response team will likely meet less frequently than the immediate phase.

- If invited, Extension should attend these meetings. If Extension is invited but unable to attend, then Extension should read the meeting minutes to stay up to date.

- At the end of the intermediate response phase, the suicide postvention response team will debrief and make note of what went well and what to improve.

- Throughout this phase, Extension should be taking notes about what is going well, any issues that may arise, and any ideas for improving the response. For guidance on what to include in these notes, please refer to the "Evaluation" section of this tool.

Long-term response (9-10 months)

-

In some cases, about 9-10 months after the death, the suicide postvention response team (SPRT), public K-12 schools, if applicable and community organizations will meet to determine long-term postvention plans.

- Extension should continue to fulfill its assigned role and/or provide support as determined by these meetings. If additional support is needed by Extension to complete its role, request support through the local mental health authority (LMHA).

- Suicide postvention response team (SPRT), public K-12 school, if applicable, and community organizations:

- Identify how ongoing risk assessment will occur through existing community channels such as workplace or school counseling centers.

- Determine what outreach or support services will be available for anniversaries or other significant events or dates.

- Consider ways to build community resilience, such as suicide prevention training or policies to reduce access to lethal means.

- Extension could be involved in this step to provide Mental Health First Aid (MHFA) trainings through the Coast to Forest Project or to promote rural resilience through the Farm and Ranch Stress Assistance Network.

- Complete an evaluation of postvention efforts to identify what went well and what to improve.

- All previous notes from Extension about what went well and what to improve will be used during this step.

- Update postvention protocols based on the evaluation findings.

Types of postvention responses

Postvention responses may differ depending on the specific circumstances surrounding a death. Below is an overview of four different types of postvention responses meant to act as an introduction to each type of response. If Extension is involved in one of the following types of postvention response, follow the instructions of the suicide postvention response team.

School-based responses

In the event of a suspected student suicide at a public K-12 school, public university, or a private post-secondary school in Oregon, the school should notify its local mental health authority (LMHA) per state law. The school will be expected to work with the local mental health authority (LMHA) and other community partners to follow the communication and response protocol for youth suicides described in the “Policy context” section. School-based postvention responses should pay extra attention to supporting those who may have witnessed the death (such as janitors, custodial staff, students, staff, teachers), external communications and notifications to students and their families, what supports will be provided on campus for staff and students, any communications with the media, and memorialization. To learn more about school-based postvention in Oregon, refer to “Developing Comprehensive Suicide Prevention, Intervention and Postvention Protocols: A Toolkit for Oregon Schools.”

Regarding memorialization specifically, it is best practice for schools to treat all student deaths the same way. Generally, schools should not create permanent physical memorials or hold the funeral service on campus, as this can inadvertently sensationalize or romanticize the death. Instead, the school and the suicide postvention response team work collaboratively with the student’s loved ones to coordinate an appropriate memorial. This may include a temporary memorial on school property that is regularly monitored by school staff. For further guidance on memorials, refer to the “Memorialization” section of After a Suicide: A Toolkit for Schools.

Workplace responses

In the event of a suspected suicide in a workplace of someone 24 years or younger, the workplace should notify their local mental health authority (LMHA) per Oregon law. In this case, the workplace will be expected to work with the local mental health authority (LMHA) and other community partners to follow the communication and response protocol for youth suicides described in the “Policy context” section.

All workplace-based postvention responses, regardless of the age of the decedent, should provide support to the family and employees. This will likely include highlighting crisis counseling services and employee assistance programs. For further guidance on workplace postvention, refer to A Manager’s Guide to Suicide Postvention in the Workplace: 10 Action Steps for Dealing with the Aftermath of Suicide

Cluster response

While suicide clusters are relatively rare (accounting for roughly 1%–13% of suicide deaths), they can have a considerable community impact and create a sense of fear or worry about additional suicides. To quickly identify and respond to suicide clusters, it is vital to have a routine monitoring system in place for suicides and suicide attempts. In Oregon, you can find this data in the Oregon Vital Statistics Annual Reports, the Violent Death Data Dashboard, and the Monthly Suicide-Related Data Reports, accessed from the OHA website on the Suicide Prevention: Data and Analysis page.

Once a cluster has been identified, the response should include suicide bereavement support, coordination with media channels, monitoring of social media, identifying and providing support for those at risk, and population-based support and prevention efforts. If additional support is needed, the postvention response lead can reach out to the Suicide Rapid Response program from Lines for Life. Suicide Rapid Response is a free statewide program that can provide additional support to postvention responses involving the death of an individual under the age of 24.

Murder-suicide

A murder-suicide is when someone kills one or more people and then themselves within a short timeframe. Loss from murder-suicide is traumatic and stigmatized. This means that those bereaved can feel isolated and may be reluctant to talk about the deaths. There is a notable lack of evidence about what support services or interventions are most effective after a murder-suicide, but what is clear is that media coverage should be factual, sensitive to those bereaved, avoid graphic details and sensationalization, and include suicide prevention resources.

Media and communication

Media is a powerful tool that can profoundly impact a postvention response. We know that media reporting on suicide death can contribute to suicide contagion or the Werther effect as described in articles by Niederkrotenthaler as well as Pirkis and their co-authors. According to Haw, suicide contagion refers to the increased risk of suicide or suicidal behavior after someone is exposed to suicide. To help prevent contagion, follow the communication protocol discussed in the “Policy context” section. This protocol outlines how, when, and to whom information is communicated during a postvention response in addition to adhering to safe reporting practices.

Safe reporting practices

Ackerman notes that safe media reporting minimizes suicide contagion risk through several key practices including using destigmatizing language, promoting help-seeking behaviors, and avoiding sensationalizing or romanticizing suicide.

Several websites are very helpful for identifying and practicing destigmatizing language including Reporting on Suicide, the Centre for Suicide Prevention and the American Association of Suicidology. To help reduce the stigma surrounding suicide, remember to choose your words carefully. Below is some general guidance on what language to use and avoid.

| What to avoid: | What to use: |

|---|---|

| ☐ Instead of “completed suicide,” “successful suicide,” or “committed suicide,”… | ✓ Use neutral language like “died by suicide,” “death by suicide,” or “killed himself/herself/themselves.” This is to avoid framing suicide as a crime or a positive outcome. |

| ☐ Instead of “unsuccessful suicide” or “failed suicide,” … | ✓ Use more neutral language like “suicide attempt” or “nonfatal suicide attempt.” This is to avoid framing a death by suicide as a positive or desirable outcome. |

| ☐ Instead of “suicide epidemic” or “suicide deaths are skyrocketing,” … | ✓ Use language like “increasing rates of suicide” or “deaths by suicide are rising.” This is to avoid sensationalist language and frame the issue more accurately. |

| ☐ Instead of “hotspot” when referring to a place where multiple suicides have occurred… | ✓ Use more neutral language like “frequently used locations.” This is to discourage additional suicides in the same location. |

Sources: American Association of Suicidology, Reporting on Suicide, Centre for Suicide Prevention and Suicide Postvention: Going Beyond Prevention and Intervention.

In addition to stigmatizing language, avoid other practices that have been linked to contagion and may perpetuate harmful ideas. Table 3 explains these harmful practices and provides alternatives based on current best practices. Remember that all communications should adhere to these safe reporting practices.

| What to avoid: | What to do: |

|---|---|

| Don’t disclose the method or specific location of the death. | Do report the death as a suicide (with permission from the family) and keep any location mentioned general. |

| Don’t include pictures or videos of the location or method. | If images must be used, choose pictures that show people in life or are related to help-seeking (for example, an image of a crisis hotline logo). |

| Don’t disclose the contents of a suicide note, final text, or last post on social media. | If a note was found, simply state that a note was found and that it is under review. |

| Don’t speculate about or oversimplify why someone died by suicide. | Do acknowledge that suicide is a complex topic and provide information about suicide warning signs and risk factors. |

| Discourage prominent, repeated and sensationalized media coverage, particularly by crime reporters. | Instead, health reporters should write news stories in consultation with mental health professionals or suicide prevention experts. |

| Don’t use negative stereotypes or perpetuate myths about mental health or suicide. | Ensure that the information provided is factual, up-to-date and from trusted sources. |

| Don’t glorify or romanticize suicide as a positive outcome. | Instead, the tone should encourage help-seeking, emphasize hope and convey that recovery is possible. |

| Don’t present suicide or suicidal behavior as a common method of coping. | Do highlight positive coping skills and effective treatments for mental health conditions. Always include resources like the National Suicide Prevention Lifeline and Crisis Text Line, and local crisis hotlines. Ensure that any resources included are up-to-date. |

| Don’t include personal details about the decedent. | Do keep information provided about the decedent general and be respectful to those bereaved by suicide. |

Sources: American Association of Suicidology, Reporting on Suicide, Action Alliance Framework for Successful Messaging and Media Guidelines for Reporting on Suicide: 2017 Update of the Canadian Psychiatric Association Policy Paper.

Table 4: Media communications checklist

If Extension is asked to share resources as a part of postvention efforts, use the checklist below to ensure that safe reporting practices are followed. A copy of this checklist is also available in Appendix D. For example, for communications that meet these criteria, please see the communication templates in Appendix F.

- Follow the talking points for community-facing communications that respect the wishes of the decedent’s family as determined by the communications team.

- Include local and/or national resources such as local or national crisis hotlines, community mental health services, or informational resources. The Suicide Prevention Resource Center is a comprehensive national resource that can serve as a starting point.

- Check that resources are factual, up-to-date, and from trusted sources, with working phone numbers, email addresses and websites.

- Use destigmatizing and neutral language that avoids sensationalizing or romanticizing suicide.

- Replace “completed suicide,” “successful suicide,” or “committed suicide” with “died by suicide,” “death by suicide,” or “killed himself/herself/themselves.”

- Replace “unsuccessful suicide” or “failed suicide” with “suicide attempt or “nonfatal suicide attempt.”

- Replace “suicide epidemic” or “suicide deaths are skyrocketing” with “increasing rates of suicide” or “deaths by suicide are rising.”

- Replace “hotspot” with “frequently used locations.”

- Use a tone that encourages help-seeking behaviors, emphasizes hope and conveys that recovery is possible. The tone and information presented should also be respectful to those bereaved by suicide.

- If images are used, they should show people in life or promote help-seeking, for example, a crisis hotline logo.

- Avoid oversimplifying suicide and its causes by acknowledging suicide as a complex public health issue. This can also be done by providing information about suicide warning signs and risk factors.

- Ensure that your communication is accessible. The ADA National Network provides tips and tools to make information more accessible for people with disabilities. At a minimum:

- Use alt text for photos or graphics. Alt text should succinctly describe the image and should end with a period.

- Use plain language and avoid jargon.

- Use sans serif (e.g., Arial, Kievit) or simple serif fonts such as New Century Schoolbook.

- Text and images should have a contrast ratio of 4.5:1 or better. You can test the contrast ratio with the WebAIM Color Contrast Checker.

- For hashtags, capitalize the first letter of each word, for example, #SuicidePrevention.

- For audio or video content include closed captions, subtitles or transcripts.

- For more resources on accessibility, please see the “Accessibility” section in Appendix H.

Evaluation and assessment of response

According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, evaluation provides a systematic way to assess a program or intervention and identify how it can be improved in the future. Simply put, the National Suicide Prevention Alliance indicates that evaluations provide insight into what worked well, what did not, and places to improve moving forward, which ensures that community needs are being met.

Regarding postvention evaluations, Extension will be “plugging into” a larger postvention response that should include an evaluation component. In practice, this means that Extension faculty and staff will likely be expected to follow a predetermined evaluation plan rather than making an evaluation plan. The exact types and methods of data collection may vary between postvention responses.

Table 4: Data commonly collected

- Demographics such as age, race, ethnicity, gender, relationship to the decedent, family history of suicide or mental health conditions, etc.

- Number of calls to 911, 988 or crisis hotlines.

- Number of visits to local emergency rooms or urgent cares.

- Number of visits to school-based health centers.

- Service use and satisfaction data for local mental health, bereavement or outreach services.

- Outcome measures like mental health symptoms, grief, social support, suicide ideation, and suicide attempts.

- Examples of existing outcome measures that have been used in postvention evaluation are the Beck Depression Inventory, Grief Experience Questionnaire, Patient Health Questionnaire and Suicide Behaviors Questionnaire-Revised.

Sources: Support after a Suicide: Evaluating Local Bereavement Support Services, Evaluating Postvention Services and the Acceptability of Models of Postvention: A Systematic Review, and Deschutes County Health Services Suicide Communication and Response Policy and Protocol.

Ethical considerations

When undertaking a postvention evaluation, additional ethical considerations must be addressed, particularly around the informed consent process and comparison groups. As described by the National Suicide Prevention Alliance, informed consent refers to the process in which potential participants receive information about the evaluation, what will be expected of them if they choose to participate, information about confidentiality, and potential risks and benefits. For example, both the National Suicide Prevention Alliance and National Institute of Mental Health indicate that postvention evaluations will likely include limits to confidentiality if a participant discloses the intent to harm themselves. These limits must be clearly discussed in the informed consent process. Additionally, clear response procedures should be disclosed so that potential participants know what supports and steps would be taken if they disclosed suicidal thoughts or behaviors.

The National Institute of Mental Health further indicates that comparison groups refer to a group of participants that either receive no treatment, treatment as usual, or a different treatment than the intervention group. In postvention evaluation, there is a concern about the level of risk for participants in a nontreatment group or about potentially unknown risks for participants receiving a new intervention. These risks must be seriously considered and underscore the need for integrated risk monitoring and safety planning throughout an evaluation.

To learn more about ethical considerations in suicide research and evaluation and current standards, consult the National Institute of Mental Health’s Conducting Research with Participants at Elevated Risk for Suicide: Considerations for Researchers

Policy considerations

For all suicide postvention responses involving the death of an individual 24 years or younger, OAR 309-027 requires an identified evaluation process for community partners, as outlined by the Oregon Health Authority. The evaluation must include “an assessment of the effectiveness of meeting the needs of grieving families and families of choice; friends or others with relationships with the decedent; and the wider network of community members impacted by the suspected youth suicide”. If Extension is involved in a postvention response for an individual 24 years or younger, then Extension may be expected to complete this evaluation process. Details and guidance should be outlined in the applicable response protocol. Any questions or concerns should be directed to the applicable local mental health authority (LMHA).

The Oregon Health Authority also requires that each local mental health authority (LMHA) must collaborate annually with community partners to review the communication and response protocols as outlined in OAR 309-027. The results of this review and any revisions are sent to the OHA youth suicide prevention policy coordinator. If Extension is asked to collaborate with this review, Extension should attend any relevant meetings or participate as indicated by the local mental health authority. Please note that Extension may not be asked to collaborate on this review.

As mentioned in the “Timeline” section, Extension faculty and staff should take notes throughout the postvention process on what went well, what did not and what could be improved. Taking notes about these observations as they happen helps lessen the impact of recall bias. It can provide valuable insight that contributes to evaluation efforts. Below are some guiding questions that can be used to structure your notes:

- What aspects of the postvention response are going well?

- What issues have you encountered? How could these issues be avoided in the future?

- Are there any aspects of the postvention response that are unclear or confusing? If so, what aspects?

- What aspects of the postvention response could be improved?

- Are there any community partners, groups, organizations, or individuals that are missing or not represented in the postvention response? If so, who are they?

Please note that if Extension is involved in the evaluation process for community partners, you may be asked to use a different set of guiding questions. In that case, defer to the questions outlined in the evaluation process for your local county or community.

Limitations

The most significant limitation of this tool is the use of a nonsystematic literature review strategy. Instead, a snowballing strategy was employed for both published and gray literature. Gray literature refers to research or materials from sources other than peer-reviewed journals or books (such as government reports). Initial literature was identified using the following search strings in PubMed, Google Scholar, and Google: "suicide" OR "postvention" OR "post intervention" AND "community." Once relevant articles were identified, both forward and backward snowballing methods were employed to identify additional relevant articles. Another limitation of the tool is its general scope, which may not account for some of the variation seen in postvention responses at local levels. Additionally, while the field of postvention research has grown in the past few decades, there remain gaps in the literature that are reflected in this tool. Notable gaps in the larger postvention literature include limited publicly available evaluation efforts (particularly long-term evaluations and evaluations with comparison groups), nonfamily members who are bereaved by suicide, people bereaved by suicide who do not seek treatment or services, older adults, publicly available postvention plans for non-school settings, overrepresentation of women in bereavement treatment and evaluation and underrepresentation of minority groups. Furthermore, since Oregon is the first state with legislative mandates for postvention, the current policy literature is limited.

Conclusion

Suicide postvention is a multifaceted and complex process that often varies. The purpose of this tool is to act as an introduction to postvention practices and highlight the role of OSU Extension within existing postvention response frameworks. While this tool was developed with a specific focus on OSU Extension involvement in postvention response, we hope that its contents can help Extension organizations around the country as well as other community partners.

Acknowledgments

The authors gratefully acknowledge the following contributions of our valued

community partners: Chris Hawkins from the Corvallis School District, Meghan Chancey from the Baker County Health Department, Jill Baker from the Oregon Health Authority, and Kris Bifulco from the Association of Oregon Community Mental Health Programs for providing feedback and reviewing the guide. The authors would also like to recognize Sandi Phibbs and Erika Carrillo for their contributions to the conceptualization of the guide. Additionally, the authors would like to thank Deschutes County Health Services for giving permission to reprint their postvention email template as a part of this guide. This study was supported through funding from the USDA National Institute of Food and Agriculture Rural Health and Safety Education Grant #2019-46100-30280 and from SAMHSA Rural Opioid Technical Assistance Program Grant # 6H79TI083266-01M001.

References

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 2022. Facts About Suicide. Accessed November 28, 2022.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 2023. National Center for Health Statistics. Accessed June 14, 2023.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 2023. Suicide Mortality by State. National Center for Health Statistics. Accessed June 14, 2022.

- Survivors of Suicide Loss Task Force. 2015. Responding to Grief, Trauma, and Distress After a Suicide: U.S. National Guidelines | National Action Alliance for Suicide Prevention. Accessed July 1, 2022.

- Aguirre, RTP., Slater, H. 2010. Suicide Postvention as Suicide Prevention: Improvement and Expansion in the United States, Death Studies, 34:6, 529-540, DOI: 10.1080/07481181003761336

- Rural Health Information Hub. Postvention. 2022. Accessed March 14, 2023.

- Blouin, SG. 2015. Senate Bill 561. Accessed November 28, 2022.

- Wagner, G. 2020. Senate Bill 485. Accessed November 28, 2022.

- Blouin, SG, Wagner, R. 2020 Senate Bill 918. Accessed November 28, 2022.

- Oregon Health Authority. 2021. Youth Suicide Communication and Post-Intervention Plan. Vol OAR 309-027-0010 § 0060. Accessed July 25, 2022.

- Oregon Health Authority. 2022. Services to Be Provided by Community Mental Health Programs. Vol ORS 430.630. Accessed July 25, 2022.

- Black, S., Guard, A. 2016. California Mental Health Services Authority. After Rural Suicide: A Guide for Coordinated Community Postvention Response.

- Crook County Health Department. 2021. Crook County Health Department Suicide Communication and Response Policy & Protocol.; :19. Accessed August 2, 2022.

- Deschutes County Health Services. 2023. Deschutes County Health Services Suicide Communication and Response Policy and Protocol. Accessed March 28, 2023.

- Frantell, K., 2022. Suicide Postvention: Going Beyond Prevention and Intervention | Mental Health Technology Transfer Center (MHTTC) Network. Accessed August 3, 2022.

- Hill, NTM., Robinson, J. 2022. Responding to Suicide Clusters in the Community: What Do Existing Suicide Cluster Response Frameworks Recommend and How Are They Implemented? Int J Environ Res Public Health, 9(8):4444. doi:10.3390/ijerph19084444

- Niederkrotenthaler, T., Voracek, M., Herberth, A., et al. 2010. Role of media reports in completed and prevented suicide: Werther v. Papageno effects. Br J Psychiatry, 197(3):234-243. doi:10.1192/bjp.bp.109.074633

- Pirkis, J., Blood, RW., Beautrais, A., Burgess, P., Skehan, J. 2006. Media guidelines on the reporting of suicide. Crisis J Crisis Interv Suicide Prev. 2006;27(2):82. doi:10.1027/0227-5910.27.2.82

- Haw, C., Hawton, K., Niedzwiedz, C., Platt, S. 2013. Suicide Clusters: A Review of Risk Factors and Mechanisms. Suicide Life Threat Behav, 43(1):97-108. doi:10.1111/j.1943-278X.2012.00130.x

- Ackerman, J., Cannon, E., Stage, D., Singer, J., Young, N. 2018. Suicide Reporting Recommendations: Media as Partners in Suicide Prevention.

- CDC. 2012. About Mental Health. Mental Health. Accessed September 7, 2022.

- Coast to Forest. 2021. Mental Health. Coast to Forest Web Library. Accessed July 3, 2023.

- Andriessen, K., Krysinska, K., Grad, O. 2017. Postvention in Action: The International Handbook of Suicide Bereavement Support. Hogrefe Publishing. Accessed July 1, 2022.

- Tal Young, I., Iglewicz, A., Glorioso, D., et al. Suicide bereavement and complicated grief. Dialogues Clin Neurosci, 14(2):177-186.

- Oregon Health Authority. 2022. Oregon Violent Death Reporting System : Injury Data. Oregon Health Authority: Public Health Division. Accessed August 22, 2022.

- Oregon Suicide Prevention. Community. Accessed August 22, 2022.

- National Suicide Prevention Hotline. We Can All Prevent Suicide. Accessed July 12, 2022.

- Suicide Prevention Resource Center. Risk and Protective Factors. Accessed July 12, 2022.

- American Foundation for Suicide Prevention. Risk factors, protective factors, and warning signs. American Foundation for Suicide Prevention. Published December 25, 2019. Accessed July 12, 2022.

- Suicide Prevention Resource Center. A Comprehensive Approach to Suicide Prevention. Suicide Prevention Resource Center. Accessed August 22, 2022.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 2022. Prevention Strategies. Suicide Prevention. Accessed August 22, 2022.

- Mishara, B.L., Martin, N. 2012. Effects of a Comprehensive Police Suicide Prevention Program. Crisis, 33(3):162-168. doi:10.1027/0227-5910/a000125

- Berman, A.L. 2011. Estimating the population of survivors of suicide: seeking an evidence base. Suicide Life Threat Behav, 41(1):110-116. doi:10.1111/j.1943-278X.2010.00009.x

- Cerel, J., Maple, M., Aldrich, R., van de Venne, J. 2013. Exposure to suicide and identification as survivor: Results from a random-digit dial survey. Crisis J Crisis Interv Suicide Prev., 34(6):413-419. doi:10.1027/0227-5910/a000220

- Cerel, J., Brown, M.M., Maple, M., et al. 2019. How Many People Are Exposed to Suicide? Not Six. Suicide Life Threat Behav, 49(2):529-534. doi:10.1111/sltb.12450

- Feigelman, W., Cerel, J., McIntosh, J.L., Brent, D., Gutin, N. 2018. Suicide exposures and bereavement among American adults: Evidence from the 2016 General Social Survey. J Affect Disord, 227:1-6. doi:10.1016/j.jad.2017.09.056

- Jordan, J.R. 2017. Postvention is prevention-The case for suicide postvention. Death Stud, 41(10):614-621. doi:10.1080/07481187.2017.1335544

- Maple, M., Cerel, J., Sanford, R., Pearce, T., Jordan, J. 2017. Is Exposure to Suicide Beyond Kin Associated with Risk for Suicidal Behavior? A Systematic Review of the Evidence. Suicide Life Threat Behav., 47(4):461-474. doi:10.1111/sltb.12308

- Pitman, A., Osborn, D., King, M., Erlangsen, A. 2014. Effects of suicide bereavement on mental health and suicide risk. Lancet Psychiatry, 1(1):86-94. doi:10.1016/S2215-0366(14)70224-X

- Marshall, D. S., Moutier, C., Rosenblum, L. B., Miara, C., Posner, M. 2018. After a Suicide: A Toolkit for Schools. Education Development Center, doi:10.4135/9781412957403.n287

- Lahad, M., Cohen, A. 2006. The Community Stress Prevention Center: 25 Years of Community Stress Prevention and Intervention. The Community Stress Prevention Center.

- 988 Suicide & Crisis Lifeline. 2021. The Papageno Effect. Accessed April 6, 2023.

- Cerel, J., McIntosh, J.L, Neimeyer, R.A., Maple, M., Marshall, D. The continuum of “survivorship”: definitional issues in the aftermath of suicide. Suicide Life Threat Behav., 44(6):591-600. doi:10.1111/sltb.12093

- Jordan, J.R., McIntosh, J.L. 2011. Grief After Suicide: Understanding the Consequences and Caring for the Survivors. Routledge. Accessed June 30, 2022.

- Ligier, F., Rassy, J., Fortin, G., et al. 2020. Being pro-active in meeting the needs of suicide-bereaved survivors: results from a systematic audit in Montréal. BMC Public Health, 20(1):1534. doi:10.1186/s12889-020-09636-y

- Oregon Health Authority. 2016. Health Systems Division Youth Suicide Intervention and Prevention Plan.

- Mental Health America. 2023. Bereavement and Grief. Mental Health America.

- Levi-Belz, Y. 2019. With a little help from my friends: A follow-up study on the contribution of interpersonal characteristics to posttraumatic growth among suicide-loss survivors. Psychol Trauma Theory Res Pract Policy, 11(8):895-904. doi:10.1037/tra0000456

- Geležėlytė, O., Gailienė, D., Latakienė, J., et al. 2020. Factors of Seeking Professional Psychological Help by the Bereaved by Suicide. Front Psychol, 11:592. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2020.00592

- Campbell, F.R., Cataldie, L., McIntosh, J., Millet, K. 2004. An Active Postvention Program. Crisis, 25(1):30-32. doi:10.1027/0227-5910.25.1.30

- Szumilas, M., Kutcher, S. 2011. Post-suicide Intervention Programs: A Systematic Review. Can J Public Health, 102(1):18-29.

- Suicide Prevention Resource Center. 2022. Provide for Immediate and Long-Term Postvention. Suicide Prevention Resource Center. Accessed July 13, 2022.

- National Institute of Mental Health. 2021. Caring for Your Mental Health. National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH). Accessed September 1, 2022.

- Cocker, F., Joss, N. 2016. Compassion Fatigue among Healthcare, Emergency and Community Service Workers: A Systematic Review. Int J Environ Res Public Health, 13(6):618. doi:10.3390/ijerph13060618

- Victoria Department of Education and Training. Self-care for school staff following the suicide or suspected suicide of a student. Suicide Response (Postvention). Accessed September 1, 2022.

- Carson, J., 2013. Spencer Foundation, Crisis Care Network, National Action Alliance for Suicide Prevention and American National Action Alliance for Suicide Prevention and American. A Manager’s Guide to Suicide Postvention in the Workplace: 10 Action Steps for Dealing with the Aftermath of Suicide. Carson J Spencer Foundation. Accessed November 17, 2022.

- O’Carroll, P. W., Mercy, J. A., Steward, J. A. 1988. CDC Recommendations for a Community Plan for the Prevention and Containment of Suicide Clusters. Morb Mortal Wkly Rep, 37(S6). Accessed July 25, 2022.

- Wagner, R., Warner, B.S., Nosse, R., Power, A., Williamson, K. J. Senate Bill 52.; 2019. Accessed November 28, 2022.

- Trauma Informed Oregon. Trauma Informed Care Principles. Trauma Informed Oregon. Accessed July 27, 2022.

- Section508.gov. 2022. Universal Design and Accessibility. Section508.gov. Accessed January 19, 2023.

- Cairn Guidance. 20147. Developing Comprehensive Suicide Prevention, Intervention and Postvention Protocols: A Toolkit for Oregon Schools.

- Arensman, E., McCarthy, S. 2017. Emerging Survivor Populations: Support After Suicide Clusters and Murder–Suicide Events. In: Postvention in Action: The International Handbook of Suicide Bereavement Support.

- Oregon Health Authority. 2021. Youth Suicide Intervention and Prevention Plan, 2021:52.

- Lines for Life. 2023. Suicide Rapid Response Program. Accessed July 6, 2023.

- Reporting on Suicide. 2022. Best Practices and Recommendations for Reporting on Suicide. Reporting on Suicide. Accessed August 12, 2022.

- Olson, R. 2022. Suicide and Language. Centre for Suicide Prevention. Accessed August 12, 2022.

- Action Alliance Framework for Successful Messaging. The Messaging “Don’ts.” Framework for Successful Messaging. Accessed August 15, 2022.

- Sinyor, M., Schaffer, A., Heisel, M.J., et al. 2018. Media Guidelines for Reporting on Suicide: 2017 Update of the Canadian Psychiatric Association Policy Paper. Can J Psychiatry, 63(3):182-196. doi:10.1177/0706743717753147

- ADA National Network. 2015. A Planning Guide for Making Temporary Events Accessible to People With Disabilities. Accessed September 6, 2022.

- Web AIM. Contrast Checker. Web Accessibility In Mind. Accessed September 6, 2022.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 1999. Framework for Program Evaluation. MMWR, 8(No. RR-11). Accessed September 12, 2022.

- National Suicide Prevention Alliance, Support After Suicide. 2020. Support after a Suicide: Evaluating Local Bereavement Support Services.

- Abbate, L., Chopra, J., Poole, H., Saini, P. 2022. Evaluating Postvention Services and the Acceptability of Models of Postvention: A Systematic Review. OMEGA - J Death Dying, 2022:00302228221112723. doi:10.1177/00302228221112723

- National Institute of Mental Health. 2021. Conducting Research with Participants at Elevated Risk for Suicide: Considerations for Researchers. National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH). Accessed September 20, 2022.

- Higgins, J., Thomas, J., Chandler, J., et al. 2019. Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions. 2nd Edition. John Wiley & Sons. Accessed January 17, 2023.

- Andriessen, K., Krysinska, K., Hill, N.T.M., et al. 2019. Effectiveness of interventions for people bereaved through suicide: a systematic review of controlled studies of grief, psychosocial and suicide-related outcomes. BMC Psychiatry, 19(1):49. doi:10.1186/s12888-019-2020-z

- Maple, M., Pearce, T., Sanford, R., Cerel, J., Castelli Dransart, D.A., Andriessen, K. 2018. A Systematic Mapping of Suicide Bereavement and Postvention Research and a Proposed Strategic Research Agenda. Crisis, 39(4):275-282. doi:10.1027/0227-5910/a000498

- Andriessen, K., Krysinska, K., Kõlves, K., Reavley, N. 2019. Suicide Postvention Service Models and Guidelines 2014–2019: A Systematic Review. Front Psychol, 10:2677. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2019.02677

- Association of Oregon Community Mental Health Programs. Connect. Accessed April 5, 2023.

- American Psychological Association. Cultural sensitivity. 2022. APA Dictionary of Psychology. Accessed September 7, 2022.

- Centre for Addiction and Mental Health. Words Matter. CAMH. Accessed September 7, 2022.