What is nitrate?

Nitrate is a form of nitrogen that is easily dissolved in water.

How common is nitrate in private wells?

1 in 5 households that use private wells for drinking water have levels of nitrate that are higher than what would be allowed in public water supplies.

How do you know if you have nitrate in your well water?

The government does not test private well water. It is up to you. Testing your water is the only way to know if nitrate is present.

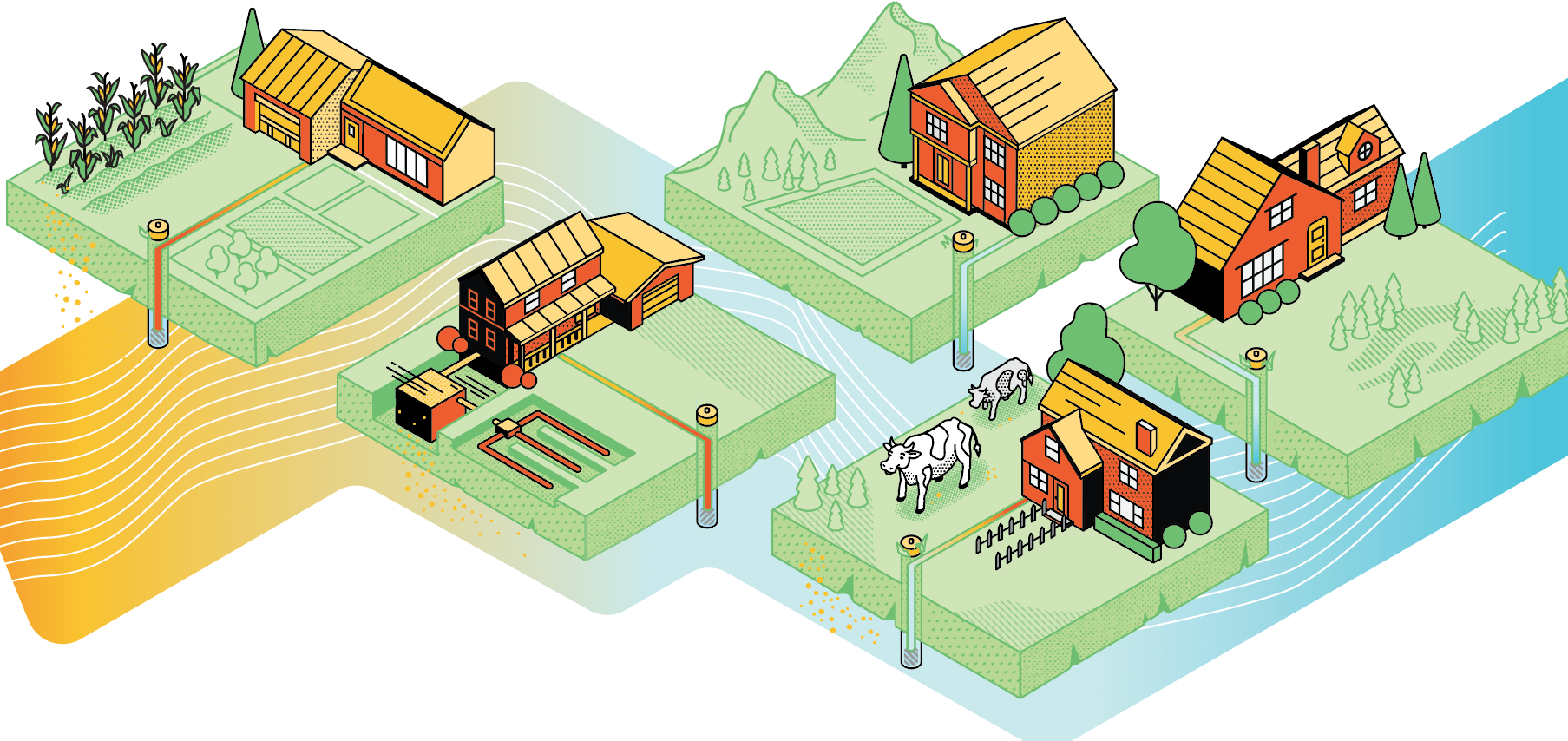

How does nitrate get in your drinking water?

Well water should not contain nitrate. Human activities can contaminate groundwater. Important sources of nitrate pollution are:

- Fertilizers

- Septic tanks

- Manure

You can remove nitrate from your drinking water with proper treatment. You can also prevent nitrate from getting in your well by reducing fertilizer use, covering manure piles, regularly cleaning your septic tank and keeping manure piles and septic systems at least 50 feet away from your well.

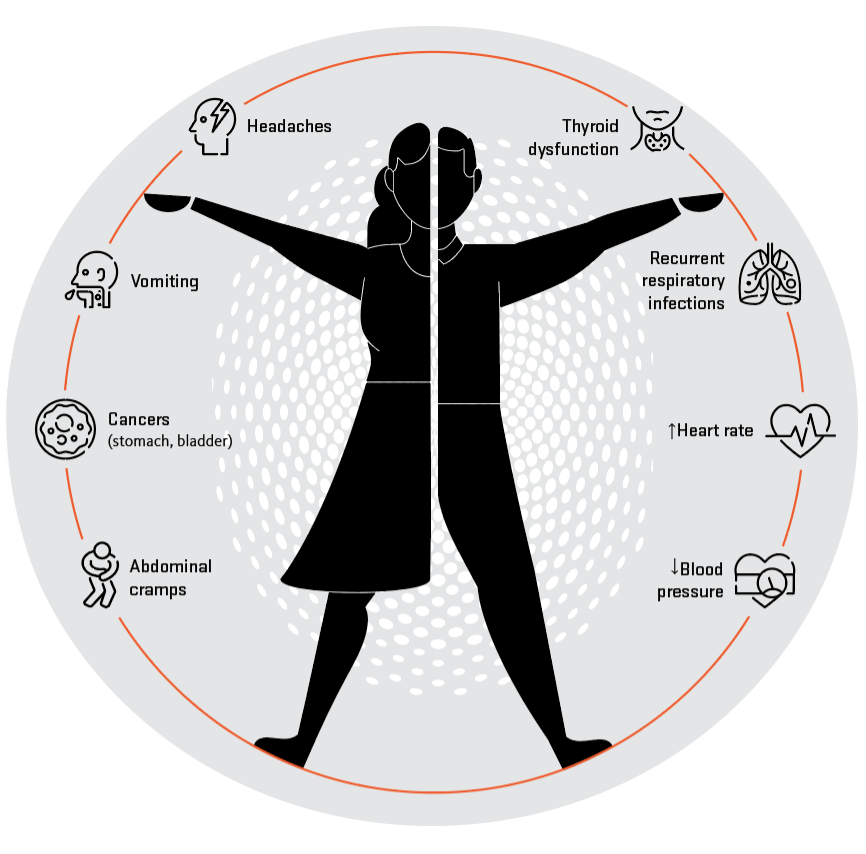

Health effects

Should I be concerned about drinking well water contaminated with nitrate?

Nitrate reduces the blood’s ability to carry oxygen, which can lead to many serious health conditions in children and adults.

For more details, please visit the Agency for Toxic Substances and Disease Registry. Reach out to your health care provider if you are concerned about nitrate exposure.

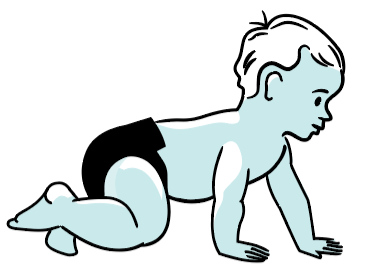

Blue baby syndrome

Methemoglobinemia (“blue baby syndrome”) is a rare but serious condition for infants and young children. It primarily affects infants younger than 6 months who are fed formula made with contaminated water. A lack of oxygen in the blood makes the skin discolor and take on a blue, bruised appearance.

During pregnancy, nitrate can increase the risk of these health conditions:

- Birth defects

- Low birth weight

- Preterm birth

- Miscarriage

Testing options

Be sure to keep a results journal and note any water quality issues. Regular well inspections can help identify potential problems early.

Where can I get my water tested?

To find accredited labs in Oregon, visit The Oregon Health Authority.

The laboratory will supply a water collection kit with specific instructions on how to collect, store, and send your water sample.

How much will a test cost?

The test will cost between $35 and $60.

Be sure to contact several labs about price and logistics before ordering tests.

Check with your local OSU Extension office, as they occasionally offer free screenings.

How often should I test?

Test your well water for nitrate every year. Since nitrate levels may change, vary testing between wet and dry seasons to get the most accurate assessment of seasonal fluctuations in your well.

If your well has elevated nitrate levels, monitor it more often. Sample your well in the fall and spring, when groundwater levels might differ, and try to identify trends in the nitrate levels.

Elevated nitrate levels may indicate the presence of other surface contaminants, including disease-causing bacteria and pesticides. You should also test for bacteria when well water shows high levels of nitrate.

| Nitrate levels | Water usage | Recommendation |

|---|---|---|

| Up to 5 ppm (mg/L) | SAFE for all uses | Test water annually, alternating between wet and dry season. If nitrate is above 2 ppm, look for possible sources near your well. |

| 5 ppm (mg/L) | If this were a public water supply, some communities would actively monitor levels and attempt to locate the nitrate source. | |

| 5–9.9 ppm (mg/L) | LEARN about nitrate sources in the local region, and what health risks are associated with nitrate. Young children and people who are immunocompromised or pregnant may want to limit the amount of untreated water that they drink or use for preparing infant formula or baby food. | MONITOR. Test water annually, alternating between wet and dry season. Look for possible pollution sources near your well. Test water for coliform bacteria. |

| 10 ppm (mg/L) | Public water system limit. If this were a public water supply, the public water system would be actively treating the water to reduce the nitrate level. | |

| 10–40 ppm (mg/L) | NOT SAFE for consumption by young children and people who are immunocompromised or pregnant. SAFE for short-term drinking for those over age 3, pets and livestock. SAFE for other household uses: bathing, washing dishes, laundry, garden irrigation. | See ACTION STEPS FOR CONTAMINATED WATER. Supervise children to ensure they do not swallow water while bathing, brushing teeth, etc. |

| More than 40 ppm (mg/L) | NOT SAFE for consumption by humans, pets or livestock. SAFE for other household uses: bathing, washing dishes, laundry, garden irrigation. | See ACTION STEPS FOR CONTAMINATED WATER. Supervise children to ensure they do not swallow water while bathing, brushing teeth, etc. |

Test results can be reported in ppm (parts per million) or mg/L (milligrams/L)

Action steps for contaminated water

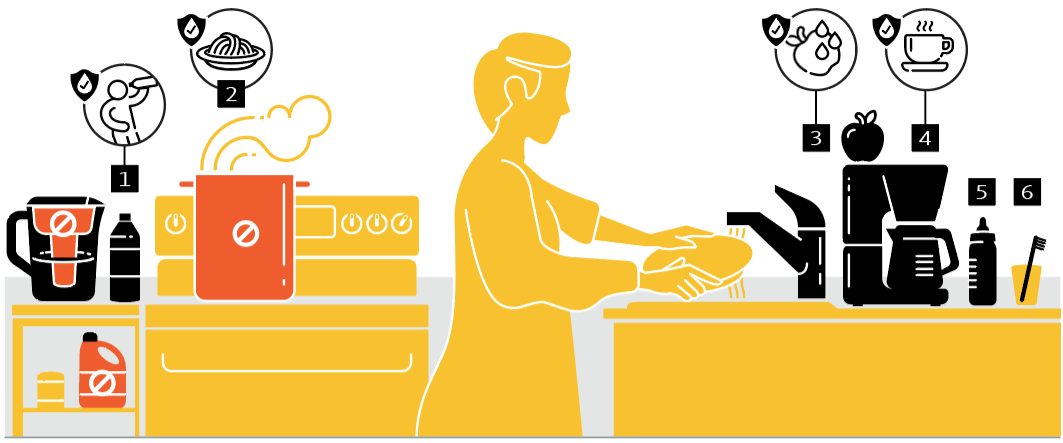

If your water has elevated nitrate levels, the safest thing you can do is use treated water or bottled water for:

- Drinking

- Cooking food such as pasta and rice

- Washing and cooking fruits and vegetables

- Mixing juices, coffee and tea

- Infant formula

- Brushing teeth

Only use bottled water if the label says it has been purified.

Nitrate does not readily get absorbed through the skin. It is safe for adults to use water that contains nitrate for:

- Showering or bathing

- Washing laundry

- Cleaning dishes

Do not...

- Do not boil tap water. Boiling will not reduce nitrate levels and could increase the level of nitrate because some of the water will evaporate but the nitrate will not.

- Do not rely on activated carbon filters such as those typically found in a water pitcher or on your refrigerator. These do not remove nitrate.

- Do not try to remove nitrate using chlorine or other disinfectants. Nitrate is a chemical, not a germ that can be “killed,” so disinfecting your water will not make it safe to drink.

Do...

- Install a water treatment system to remove nitrate from your home drinking water. Reverse osmosis, distillation, or anion exchange can be effective for nitrate removal. See page 7 for more information about treatment options.

- Treatment systems require careful maintenance for effective operation. If a treatment system is installed, you must continue to test your treated water for nitrate every year to ensure it is working correctly.

For health-related questions about nitrate in your water and additional resources regarding well maintenance, testing, and treatment, visit Oregon State University's Well Water Program.

Water treatment options

Types of water treatment and the contaminants they remove

If you have multiple contaminants in your well water, you may need to combine water treatment systems.

| Recommended water treatment systems | Additional treatment systems may be required if multiple contaminants are present | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Contaminant | Anion exchange | Reverse osmosis | Distillation | Aeration and filtration | Carbon filter | Chlorination | Oxidizing media filtration | Ozonation | Ultraviolet (UV) distillation | Water softener |

| Nitrate | Removes or partially removes | Removes or partially removes | Removes or partially removes | |||||||

| Lead | Removes or partially removes | Removes or partially removes | Only if the filter includes absorption media rated by National Sanitation Foundation | |||||||

| Arsenic | Removes or partially removes | Removes or partially removes | Removes or partially removes | May be needed for pretreatment to remove arsenic | May be needed for pretreatment to remove arsenic | May be needed for pretreatment to remove arsenic | ||||

| Color, taste or odor issues | Removes or partially removes | Removes or partially removes | Removes or partially removes | Removes or partially removes | Removes or partially removes | Removes or partially removes | Removes or partially removes | Removes or partially removes | ||

| Bacteria and viruses | Removes or partially removes | Removes or partially removes | Removes or partially removes | |||||||

| Calcium and manganese (water hardness) | Removes or partially removes | Removes or partially removes | Removes or partially removes | |||||||

| Chlorine | Removes or partially removes | Only if the filter includes absorption media rated by National Sanitation Foundation | ||||||||

| Hydrogen sulfide | Removes or partially removes | Only if the filter includes absorption media rated by National Sanitation Foundation | Removes or partially removes | Removes or partially removes | Removes or partially removes | |||||

| Sulfate | Removes or partially removes | Removes or partially removes | Removes or partially removes | |||||||

| Iron | Removes or partially removes | Removes or partially removes | Removes or partially removes | Removes or partially removes | Removes or partially removes | Removes or partially removes | ||||

| Radon | Removes or partially removes | Only if the filter includes absorption media rated by National Sanitation Foundation | ||||||||

| Uranium | Removes or partially removes | Removes or partially removes | Removes or partially removes | |||||||

| Pesticides | Removes or partially removes | Removes or partially removes | Only if the filter includes absorption media rated by National Sanitation Foundation | |||||||

| Perfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS) | Removes or partially removes | Only if the filter includes absorption media rated by National Sanitation Foundation | ||||||||

| Trichloroethylene (TCE) and other volatile organic compounds (VOCs) | Removes or partially removes | Removes or partially removes | Only if the filter includes absorption media rated by National Sanitation Foundation | |||||||

Adapted from Home Water Treatment Fact Sheet, Minnesota Department of Health

Nitrate prevention

How to protect your well water from becoming contaminated with nitrate

Protect your well head:

- Locate all wells on your property. Inactive wells that are not properly sealed can contaminate the water that supplies your well.

- Your wellhead should be 12 inches above the surface of the ground and covered with a sanitary seal to prevent materials from entering the well. Contact a well professional to make these repairs.

- Cover your well head. Well coverings provide a visual reminder of the well location and protect the well head from the weather.

- Install backflow prevention devices on outdoor faucets. These are inexpensive, screw-on, brass atmospheric pressure breakers that will stop water from being sucked backwards through a hose and down the well. These are especially important for faucets used for irrigation, livestock trough water, chemical mixing, and pressure washing.

- Do not store fertilizer, pesticides, fuels or other potentially toxic material near your well head. Spilt chemicals can contaminate your well by seeping through the soil or entering the well casing. Never pour these products down the drain because they can damage septic systems and pollute water.

Maintain your septic system:

- If you have a septic system, locate the tank and drain field. Neglecting septic systems can result in backed-up sewage and expensive repairs. Sewage could get into your well water.

- Make sure your septic tank is emptied regularly. Frequency of pumping depends on your household and septic tank size. Typically, a four-person household needs to pump about every three to four years. The OSU Extension Service or your pumping company can provide additional guidelines.

- Protect your drain field from damage. Keep vehicles, heavy equipment, and large animals away from it so that the soil does not become compacted.

- Do not irrigate, add or remove surface soil in the drain field area. Only grass or plants with short root systems should be grown over a drain field.

- Conserve water. Using a large amount of water inside your home can push wastewater through the septic system without enough time for proper breakdown to occur.

Landscaping and livestock:

- Proper use of fertilizers (and pesticides). Apply fertilizers (and pesticides) sparingly and follow the label directions — the label is the law. If you apply too much fertilizer, plants cannot use it all and it will quickly seep into the soil and can contaminate your well water.

- Store your fertilizers (and pesticides) safely. Do not store or mix fertilizers (and pesticides) where spills can enter the soil and potentially reach the groundwater that supplies your drinking water.

- Take steps to prevent runoff and soil seepage from animal pens and manure piles. These are sources of bacteria and nitrate, which could contaminate your drinking water. Ideally, animal pens would be located away from your well or any nearby streams. Manure piles would be covered and placed on a concrete pad. Even covering piles on the ground with a simple tarp during the rainy season helps reduce potential contamination of groundwater.

Nitrate treatment options

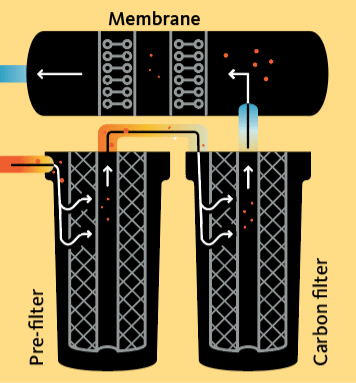

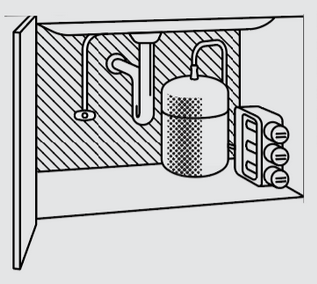

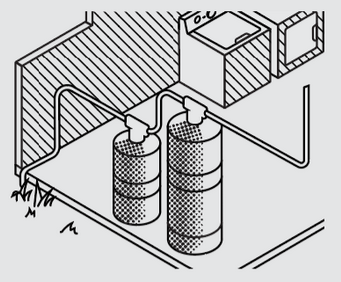

Reverse osmosis

Reverse osmosis uses energy to push water through a membrane with tiny pores. The membrane stops many contaminants while allowing water to pass through.

Pros: Removes a wider variety and greater amount of contaminants than many other treatment options.

Cons: Can create a lot of wastewater. May require pretreatment to prevent the membrane from getting clogged.

Point-of-entry cost estimate

- Initial: $5,000–$12,000

- Maintenance: $250–$500 every one to two years

Point-of-use cost estimate

- Initial: $300–$1,500

- Maintenance: $100–$200 every one to two years

Distillation

Distillers boil water, which makes steam. The steam rises and leaves contaminants behind. The steam hits a cooling section, where it condenses back to liquid water.

Pros: Removes a wider variety and greater amount of contaminants than many other treatment options. Kills 100% of bacteria, viruses, and pathogens, so you can still drink your water during boil-water advisories or if your well becomes contaminated.

Cons: Heating the water to create steam can be expensive. Water may taste “flat” because oxygen and minerals are reduced.

Point-of-entry cost estimate: N/A

Point-of-use cost estimate

- Initial: $300–$1,200

- Cost consideration: Energy to boil water

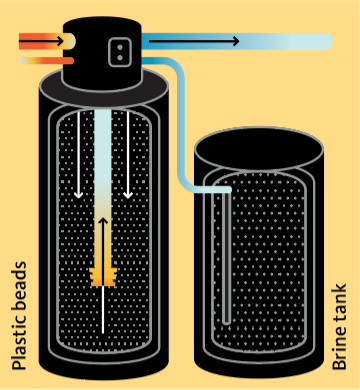

Anion exchange

Anion exchange removes dissolved minerals in the water. The owner adds sodium chloride or potassium chloride (salt), which replaces negatively charged minerals in the water.

Pros: Sodium chloride and potassium chloride are safe to handle and easy

to buy.

Cons: Anion exchange may affect how corrosive your water is and can corrode your pipes; this may be a health concern if you have copper or lead pipes. If treatment is not maintained properly, high concentrations of the contaminant can be dumped back into the water. Salt use can negatively affect the environment.

Point-of-entry cost estimate

- Initial: $1,500–$2,500

- Maintenance: $700-$900 every eight to 10 years

Point-of-use cost estimate: N/A

Cost estimates are based on quotes obtained in 2017 and research in 2018; actual costs may vary. In general, the low-end cost is for a treatment unit the homeowner installs; the high-end cost is for a treatment unit installed by a water treatment professional.

Point-of-use vs. point-of-entry treatment

Water can be treated for nitrate at the point-of-use, such as a faucet, or at the point-of-entry, at the well.

Water treatment tips

How do you know the treatment system will actually work?

The following organizations certify water treatment systems:

You can search these databases by manufacturer or chemical contaminant. Often, manufacturers will report the effectiveness by percent removal (the amount of contaminant that is removed from the water).

What are the financial considerations?

You can purchase and install a treatment unit on your own, or you can work with a treatment professional.

An alternative to water treatment is using a water delivery service or bottled water. This can be a cost-effective solution for some people. Note that bottled water is not regulated to the same standards as tap water. Water labeled as “artesian” may not be treated. Only use bottled water if the label says it has been purified by reverse osmosis or distillation.

For more information, see EPA Bottled Water Basics

Your household may also qualify for a loan (which you have to pay back) or grant (which you do not have to pay back) to help pay for water treatment. Visit OSU's well water program for information about loans and grants.

What should you consider when choosing bottled water?

Note: Beware of false claims, deceptive sales pitches, inaccurate water quality data, and scare tactics used by some water treatment companies to sell expensive and unnecessary home water treatment units. Here are some recommended questions to ask a water treatment professional.

What if your water contains multiple contaminants?

Select the appropriate treatment for the contaminant you are trying to control. No single treatment unit can remove all contaminants from water, but some units can remove multiple contaminants.

How do you find a certified water quality professional?

Search listings through the Water Quality Association.

If you work with a treatment professional, work with a licensed pump contractor or a licensed plumber. You can check this by using the Oregon Building Codes Division’s License Holder Search.

Acknowledgment: Funding for this project was provided by the National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences (NIEHS grant #R01 ES031669), an institute of the National Institutes of Health.