New and inexperienced landowners often wonder what they should do with their woodland, and the possibilities are numerous. There is no one right way to manage a forest, no single recipe to follow. Much depends on your particular interests, goals and objectives. For example, you could emphasize wildlife, timber production or recreation — or you could work to restore the forest to a previous condition. You could manage for all of these goals.

Regardless of your objectives, your choice to follow these management guidelines protects water quality, reduces weed infestations, maintains soil productivity, reduces the threat of fire and promotes forest health. In a nutshell, you are protecting the forest ecosystem and preserving options for future generations.

When we talk about forests and woodlands, we are referring to an area of trees and associated vegetation of any size — from a backyard woodlot to a tract of several hundred acres or more. Though specifics vary, these concepts apply to a wide range of forests and woodlands, from oak woodlands to mixed conifer forests.

Protect water quality

Forests produce high-quality water due to the outstanding filtering provided by woodland vegetation and soils. Many communities, such as those in Ashland and Medford, rely on water quality from forest watersheds. Protecting water quality is one of the most important public benefits that private forests can provide.

One of the main ways to protect water is to control the amount of sediment entering the watershed. While a little bit of sediment in streams is natural, excessive and chronic sediment harms fish, their spawning beds, and domestic water supplies.

Sediment is probably the biggest water pollutant on forest lands.

These best practices can help keep sediment to a minimum:

- Maintain a forested buffer along streams to filter out sediment and other pollutants that might otherwise enter waterways. See Streams and Riparian Areas: Clean Water, Diverse Habitat, EM 9244, for more specifics on riparian buffers.

- Avoid using heavy equipment in streambeds or near streams. When roads and skid trails are located within riparian zones or along streams, it is easy for runoff from the road to enter the stream itself, resulting in water pollution.

- Locate roads and skid trails away from the riparian zone and minimize the number of stream crossings to reduce the risk of water pollution.

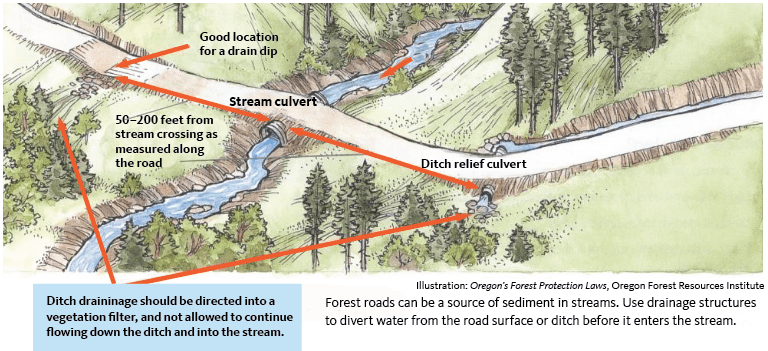

- Install and maintain water bars, drainage dips, and other water control structures to reduce runoff on roads, diverting sediment before it enters the stream.

- Adequately size culverts for storm flows. The Oregon Forest Practices Act requires all culverts in newly constructed forest roads to be able to pass a 50-year storm flow (flow expected in a major, once-in-50-years storm). This can be surprisingly large. Where feasible, favor bridges over culverts.

- Maintain adequate tree cover to reduce runoff and erosion. Harvesting and other disturbances aren’t bad, but disturbed areas should be quickly replanted. This vegetation — along with uncompacted, porous forest soil — helps facilitate the safe capture, storage and release of precipitation in the form of streamflow.

- Monitor roads, skid trails and disturbed areas periodically for runoff and erosion. It is easiest to spot problems during rainy periods.

- Restore any eroding areas by planting, seeding, installing check dams, etc.

- Follow the label on herbicides and fertilizers. Avoid applying these products on windy or rainy days or near bodies of water. The product could drift or run off into surface water.

Keep soils healthy

- Minimize soil disturbance, compaction and displacement. Undisturbed forest soils consist of about 50% pore space. This space allows for gas exchange with the atmosphere and the infiltration and temporary storage of rainwater and snowmelt. Heavy equipment compacts soils, reducing infiltration and gas exchange. This can reduce plant growth and increase surface water runoff, causing erosion.

- Confine heavy equipment to roads and designated skid trails where feasible.

- Quickly replant bare or disturbed areas to minimize erosion.

- Balance the retention of organic matter with fire hazard concerns.

Trees and other vegetation take up nutrients from the soil and recycle them through the decomposition of needles, leaves and twigs that fall to the ground. Most of a site’s nutrient “bank” is contained in the organic matter found in the topsoil itself, not the vegetation. Nutrients are added primarily through the breakdown of rock layers and inputs from nitrogen-fixing vegetation, such as alder trees.

Severe wildfire is one of the main ways nutrients can be lost from the site, so fuels and fire risk reduction promote soil conservation. When slash is added to the forest floor after thinning, allow it to decay and return nutrients to the soil.

But this organic material also represents a fire hazard. Decomposition could take years and even decades in a dry climate. Balance retention of some organic matter for long-term soil health with the elevated fire hazard it poses.

Seek advice specific to your site to strike this balance.

Manage invasive weeds

Invasive or noxious weeds compete with and displace native plants. Prevention is the best way to keep invasive weeds to a minimum.

- Keep out dirty vehicles and equipment. Alternatively, wash vehicles before entry and require contractors to do the same. Try not to import seed-contaminated fill dirt or road gravel. Clean the dirt off boots when they have been used off site.

- Periodically monitor your woodland for noxious weeds. Skid trails, roads (especially cut and fill slopes), burned areas, logged areas and other disturbed areas are more likely to harbor new weed populations than the undisturbed forest. Monitor at different times of year; some evergreen weeds are more visible in winter.

- Practice integrated pest management. Where weeds are detected, attempt to control or eradicate them using IPM. This strategy combines an array of pest control methods to achieve the best results with the least disruption to the environment. Use pesticides only under strict circumstances that minimize risk.

- Consult the Pacific Northwest Weed Management Handbook, for more information on weed management.

Reduce the threat of fire

- Learn your local fire restrictions. Contact your local Oregon Department of Forestry office for more information on fire season, restrictions and closures.

- Make your forest resistant to fire. A fire-resistant forest is one that can survive a wildfire with some scorched ground but with most of the overstory trees intact. Follow these steps to create a fire-resistant forest:

- Minimize and reduce the continuity of high-risk surface fuels. For example, landowners should treat excess slash.

- Reduce ladder fuels by thinning and pruning.

- Break up crown continuity by creating openings in the trees.

- Retain larger trees and favor more fire-resistant species, such as ponderosa pine. On larger properties, it’s difficult to treat every acre, so focus fuel-reduction treatments in strategic locations, such as ridgelines and above and below access roads. See other publications in this series in the OSU Extension Catalog, for additional information.

- Maintain access roads. Access roads facilitate quick detection and suppression of fire. Remove dense vegetation encroaching on or overhanging the road. Design and maintain access roads that meet fire suppression vehicle standards. Where possible, maintain two ways to exit your property.

Promote tree and stand health

- Assess the condition of your forest or woodland. Conduct a forest inventory. Get to know the character, topography and soil conditions of your property and the composition and structure of the trees and shrubs.

- Match tree species to site conditions; plant and thin to favor best-suited species. Feature drought-tolerant trees (pines, oaks, madrones) on dry ridgetops, areas of shallow soils, and south and west aspects. Include a bigger mix of less drought-tolerant species (Douglas-fir, true firs, incense cedar) on east, and especially, north aspects.

- Thin excessively dense stands or patches. Determine stand density. If the forest is overly dense, thin the stand or portions of it to desired levels. Treat thinning slash by burning, chipping or removing it.

- When thinning, retain vigorous, high-quality trees of desired species. When choosing “leave” trees in a thinning operation, select trees with healthy foliage that appears full.

- Provide lots of growing space around pines, oaks, and other shade-intolerant species. Provide especially wide spacing around pine leave trees. Where hardwoods are selected for retention, ensure that crowns are open to the sun and unlikely to be overtopped by other retained trees before the next thinning.

Timber harvesting

Though many woodland owners don’t manage primarily for timber production, timber harvests can generate income from a property. They also can improve forest health, reduce fire risks and create new wildlife habitat.

In a commercial thinning, some trees in a stand are removed in order to favor the growth of the remaining trees.

In a patch cut or clearcut harvest, most or all trees in an area are cut. This approach creates favorable conditions for tree species that grow best in full sun.

There are many other harvest methods, and each has important implications for future tree regeneration and growth and development of habitat.

- Match the harvest method to your objectives and become familiar with the implications of the harvest for the future development of the forest.

- Learn the Oregon Forest Practices Act requirements on timber harvesting. Numerous rules govern notification, post-harvest reforestation, roads and stream crossings, slash abatement, wildlife tree retention, and riparian buffer zones.

- File a notification of operations prior to harvest. The Oregon Department of Forestry issues notifications. Depending on the type and location of the operation and proximity to streams and wildlife habitat, you may need a written plan.

- Consider working with a consulting forester to help prepare for and manage the timber sale and harvest. A consultant can help choose a harvest method to meet your objectives, determine timber volumes and values, mark boundaries and timber to be cut, find a buyer, locate a logger, and manage the harvesting operation, among other tasks.

- Find a reputable logger and use a contract. Check references and ask to view other jobs the logger has completed.

The practices described in these guidelines all relate to timber harvesting, especially those related to protecting water quality through the proper design, location and maintenance of roads, road drainage and stream crossings.

Reforestation

- Choose species adapted to your site and match them to site conditions. Make sure the seedlings are from the correct seed zone and elevation, so that they will be genetically adapted to the site. Consult seed zone maps; most nurseries can help you make the right match.

- Keep seedlings cool and make sure the roots stay moist. Many reforestation failures trace back to poor handling and planting techniques.

- Plant in winter when seedlings are dormant and soils are moist.

- Remove competing vegetation. Shrubs and grass can quickly overwhelm planted seedlings. Weed prior to planting and maintain a weed-free area within 3 to 5 feet of the seedling through at least the first summer.

Maintain and improve wildlife habitat

- Inventory the property for habitat characteristics and keep records of wildlife observations.

- Develop desirable habitat for the species you want to foster. If you want to support a variety of wildlife, promote a diverse forest composition and structure in part or all of your stand. This will maximize the number of habitat niches and make more food, water, and cover available. See other publications in this series in the OSU Extension Catalog for more information.

- Favor a variety of tree species when thinning, including some of different sizes. Vary the spacing from place to place. Maintain some dense, unthinned clumps. Create openings and edges of varying sizes. Feature shrubs, herbs and grasses.

- Retain hardwood where possible. Consider favoring large oaks as “leave trees.” Oak habitat is particularly rich in species.

- Look at the big picture. While habitat diversity is generally desirable, consider the surrounding area and whether your property may provide special habitats not found in the vicinity. On a landscape scale, your biggest contribution to overall habitat diversity might be favoring one particular type of forest or habitat (oak woodland or riparian hardwoods, for example), rather than trying to maximize habitat diversity on your individual parcel. Also, consider how your property might serve as a corridor between adjacent habitats and what could be done to maintain connectivity.

- Leave some dead wood. Dead wood is a critical source of food and shelter for many species, from woodpeckers to small mammals.

- Maintain some snags (especially those over 10 inches in diameter at chest height) in places where they will not interfere with other management objectives.

- Maintain some live trees (especially hardwoods) with evidence of decay.

- Leave large down wood (logs greater than 10 inches in diameter at the small end).

- Leave a few slash piles at strategic locations in the forest.

Follow the rules

The Oregon Forest Practices Act governs forestry operations such as commercial timber harvesting, road-building, reforestation, precommercial thinning, chemical applications and prescribed burning.

If you are undertaking a forestry operation, follow the guidelines laid out in the Forest Practices Act. Submit a notification of operations to the Oregon Department of Forestry before you start. A notification is required when:

- Using power-driven machinery on your property.

- Harvesting a small patch of timber and selling the logs.

- Applying herbicide on forest lands.

- Completing a fuels-reduction project that generates slash.

- Building a road across a stream to access a timber stand on the other side.

- Converting a forested area to another land use.

Learn more about the forest practices act from the Oregon Department of Forestry or the Oregon Forest Resources Institute. Get to know your Oregon Department of Forestry stewardship forester, especially if you are contemplating a forestry operation.

References

What are Forestry Best Management Practices? SUNY College of Forestry and Environmental Science.

Forestry Best Management Practices. American Forest Foundation

Oregon Forest Practices Act. Oregon Department of Forestry

Oregon’s Forest Protection Laws: An Illustrated Manual, Third Edition. Oregon Forest Resources Institute.

© 2019 Oregon State University.

Extension work is a cooperative program of Oregon State University, the U.S. Department of Agriculture, and Oregon counties. Oregon State University Extension Service offers educational programs, activities, and materials without discrimination on the basis of race, color, national origin, religion, sex, gender identity (including gender expression), sexual orientation, disability, age, marital status, familial/parental status, income derived from a public assistance program, political beliefs, genetic information, veteran’s status, reprisal or retaliation for prior civil rights activity. (Not all prohibited bases apply to all programs.) Oregon State University Extension Service is an AA/EOE/Veterans/Disabled.