Oregon is fire country. With our hot, dry summers and abundant fuels, it is not a matter of if a wildfire will occur, but when. Wildfire can threaten homes, property and lives. But it also plays important ecological roles, such as reducing fuels and recycling nutrients.

Historically, not all wildfires in Oregon were the same. Some burned much hotter than others. Some forests burned more frequently, but the fires were less intense. Generally, the state’s wetter regions tended to experience intense but infrequent fires, while drier locations experienced much more frequent low- and moderate-intensity fire. In recent decades, hotter, drier summers and a buildup of flammable vegetation have led to an increase in fire size and severity in these drier areas of the state.

For landowners, living with wildfire means protecting your home and property from damaging fires while creating a forest or woodland that is fire-resistant — meaning one that can experience a wildfire and survive, more or less intact. For communities, living with wildfire means suppressing wildfires when necessary, but also encouraging the use of prescribed fire at times and in locations where appropriate. This approach is summed up in the vision statement of the National Cohesive Wildland Fire Management Strategy: “To safely and effectively extinguish fire when needed; use fire where allowable; manage our natural resources; and as a nation, to live with wildland fire.”

Personal wildfire preparedness

- Get ready. If a wildfire occurs, you may be evacuated. Become familiar with the three levels of evacuation preparedness (Be Ready, Be Set, Go!). You should always be at level 1 (Be Ready). At level 2 (Be Set), you should be ready to evacuate at a moment’s notice. At level 3 (Go!), leave immediately.

- Create an emergency kit and an evacuation plan that lists what you need to take with you, where it is, and how you are going to get it away from your property (the six Ps).

- Know your neighbor. In rural areas, your neighbor can be at your home faster than any emergency response. Establish lines of communication to notify each other in the event of a wildfire.

Remember the 6 P’s

Keep these items ready in the event

you need to evacuate:

- People and pets

- Papers, phone numbers and documents

- Prescriptions, vitamins and

eyeglasses - Pictures and irreplaceable

memorabilia - Personal computers, hard drives, cellphones, chargers, batteries, etc.

- Plastic (credit cards, ATM cards) and cash

The Home Ignition Zone

Homes built in the wildland-urban interface, where urban and suburban areas intermingle with the surrounding forest or other wildland vegetation, are at high risk from wildfire.

Home ignition in a wildfire typically occurs when:

- Radiant heat from nearby burning vegetation or structure fires rises to a level that induces combustion.

- Surface fires reach the walls or roof of the home.

- Embers, also known as firebrands, fall on combustible materials on or around the home.

Most commonly, homes are lost in wildfires when they come into contact with embers or low-intensity surface fires — not from a giant wall of flames from an advancing wildfire.

The Home Ignition Zone is defined as the home itself and everything around it out to 100 feet (out to 200 feet on steeper slopes). The condition of your HIZ is the primary factor that determines whether your home will survive a wildfire. The good news is that there is much you can do to reduce your risk!

The HIZ is divided into three zones:

- The immediate zone, which includes the home and extends outward for 5 feet.

- The intermediate zone, which extends from 5 to 30 feet.

- The extended zone, which extends from 30 to 100 feet (more on steeper slopes).

The actions you take vary by zone.

Immediate zone (0–5 feet)

This zone includes the home itself and everything out to 5 feet from the foundation.

Chimney to eaves

- Consider the composition and condition of your roof. The roof is the most vulnerable component of a home when it comes to wildfire. The roof should be made of a combustion-resistant material, such as those in Class A (clay tiles, metal, slate, composition shingles).

- Keep the roof and gutters free of debris and tree litter. This is one easy and effective way to prevent embers from igniting there. Combustible gutters, such as those made of vinyl, can fail under radiant heat, exposing the underlying surface to direct flame contact.

Eaves to foundation

Windows and siding that fail due to radiant heat exposure can expose the interior of the home or the underlying structure, both of which are more susceptible to direct flame contact and ember showers. Install metal mesh screening with

1/8-inch openings, which has been shown to reduce the chances of embers entering the home.

Foundation to 5 feet

- Maintain a noncombustible area at least 5 feet wide around the base of your home. Use gravel, rock mulches or hard surfaces such as brick and pavers.

- Remove dead vegetation and debris under decks. Never store lumber, firewood or other flammable materials underneath. Install screen under low-profile decks to prevent ember entry.

- Assess your storage practices. Keep accessories such as patio furniture, gas grills and even welcome mats in an enclosed storage area or away from the home when the wildfire threat is high. These can be a source of ignition under an ember shower.

Intermediate zone (5–30 feet)

This zone should be “lean, clean and green.” Discourage fire-prone, flammable vegetation within 30 feet of the house to keep it “lean.” Maintain a low density of vegetation in general. Keep it “clean” by preventing the accumulation of dead vegetation or flammable debris within this area. Keep plants healthy and “green” by watering sufficiently during fire season. For most homeowners, the lean, clean and green area is the residential landscape. This zone often has irrigation, contains ornamental plants and should be maintained annually.

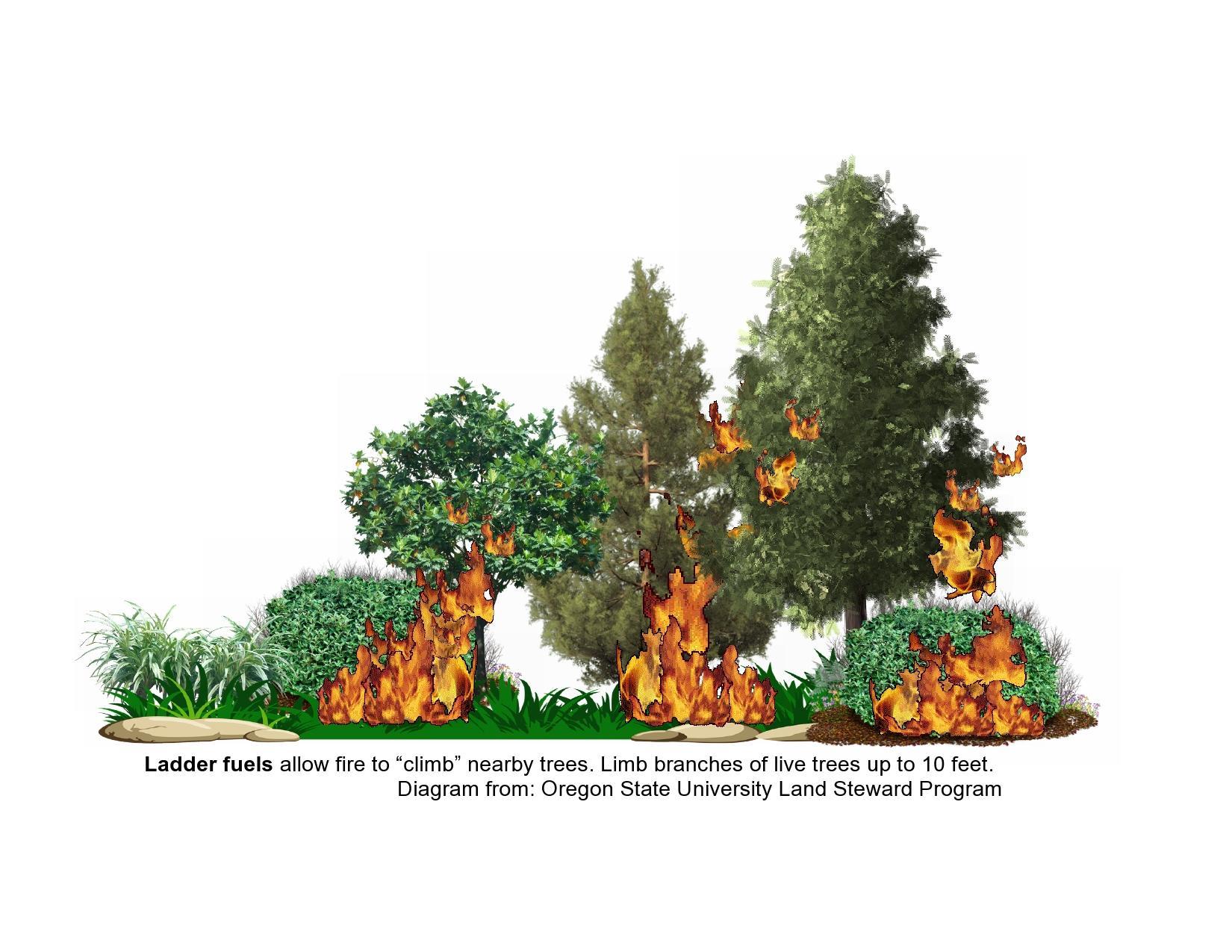

- Prune tall trees up to 6–10 feet. When pruning shorter trees, maintain at least a 50% crown. Proper pruning reduces the chance that a surface fire will use low hanging limbs to move into the upper canopy. Lower limbs as well as small trees and shrubs are known as ladder fuels because fire can “climb” into the upper canopy where fires can become more intense and spread faster.

- Prune individual tree canopies at least 10 feet away from the home or attached structures. Individual trees and clumps of trees should be spaced at least 15–20 feet apart between tree tops, with a greater distance on steeper slopes.

- Remove dead plant material such as leaves, needles and twigs.

- Replace flammable plants such as juniper or Leyland cypress with fire-resistant plants.

- Keep grass watered (green) and mowed to 4 inches.

- Create fuel breaks with driveways, walkways, paths and other hardscapes.

- Avoid large, contiguous areas of bark mulch, which is flammable, especially when dry. Keep bark moist and break it up with hardscapes, lawn or other, non-flammable materials.

- Park vehicles in areas clear of vegetation and maintain fuel breaks around secondary structures. Vehicles and other nearby structures such as gazebos and sheds can be a source of ignition and fuel.

Extended zone (30–100+ feet)

This area extends from the 30-foot lean, clean and green area out to at least 100 feet, and up to 200 feet or more on steeper slopes with thick vegetation. It typically lies beyond the residential landscape and often consists of naturally occurring plants such as conifer and hardwood trees, brush, weeds and grass.

You may find that your Home Ignition Zone overlaps onto adjacent properties. Work closely with neighbors to reduce your shared risk.

- Remove dead vegetation, including dead shrubs, fallen branches, thick accumulations of needles and leaves, etc.

- Mow grass to 4 inches high or less.

- Remove invasive weeds such as blackberries, cheatgrass and Scotch broom.

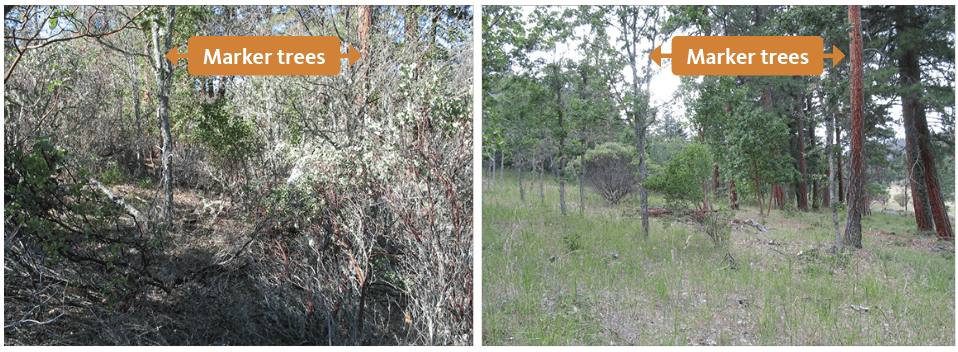

- Remove ladder fuels such as low tree branches, shrubs growing underneath larger trees and small trees growing between mature trees.

- Thin out dense patches of trees and shrubs to create separation between them in order to slow the spread of fire. Breaking up the canopy, or reducing the connection between tree crowns, reduces the chance that high-intensity crown fires will approach your home. Such fires can create a major source of radiant heat as well as embers. In some cases, however, mature stands of healthy, fire-resistant trees, such as ponderosa pine and bigleaf maple, catch and filter embers that would otherwise land on the home.

- Continue pruning and removing ladder fuels out to the farthest extent of the Home Ignition Zone, from 100 feet to 200 feet.

Beyond the Home Ignition Zone: creating a fire-resistant woodland

The Home Ignition Zone extends out to approximately 100 feet from the home (up to 200 feet or more depending on slope, aspect, vegetation type and density). But your fuels management activities shouldn’t stop there. You can create a forest or woodland that is more fire-resistant — that is, one that is able to experience a wildfire and survive more or less intact. Research and experience in forests throughout the American West show four basic principles for creating fire-resistant forests:

- Reduce the amount of surface fuels, such as small branches and other debris lying on the forest floor. This does not mean removing all woody material or litter; just reduce the heavier concentrations. However, it is important not to leave bare ground, which may encourage invasive plants that are often highly flammable.

- Reduce ladder fuels, such as lower tree limbs, small trees, and brush growing under larger trees. Reducing surface and ladder fuels reduces fire intensity and heat production and makes it harder for a fire to ignite tree crowns.

- Create space between individual trees or clumps of trees to reduce the potential for tree-to-tree fire spread.

- Keep larger trees of fire-resistant species, which are the trees best able to survive a fire.

Access

- Clearly post your home address at the foot of the driveway and at every junction on a shared road. Firefighters cannot defend what they cannot find or access.

- Make sure your driveway has the proper clearance for large fire equipment. Firefighters will not defend a structure that has inadequate ingress and egress routes or one that lacks defensible space.

Follow the rules

Several state and county regulations require landowners in areas designated as high-risk to follow guidelines regarding fuels reduction, setbacks, access to the property and more. See References, below.

Certain activities, such as using chain saws and other power-driven equipment, open burning, and forestry operations, may be restricted or prohibited during fire season. Be sure you know where to access this information for a complete list of restrictions in your area. See Forests and Woodlands: Protecting an Ecosystem, EM 9245.

References

Reducing Wildfire Risks in the Home Ignition Zone, National Fire Protection Association.

Standard for Reducing Structure Ignition Hazards from Wildland Fire, National Fire Protection Association 1144

Reducing Fire Risk on Your Forest Property, PNW 618

Oregon Forestland-Urban Interface Fire Protection Act, or Oregon’s Defensible Space Law

© 2020 Oregon State University.

Extension work is a cooperative program of Oregon State University, the U.S. Department of Agriculture, and Oregon counties. Oregon State University Extension Service offers educational programs, activities, and materials without discrimination on the basis of race, color, national origin, religion, sex, gender identity (including gender expression), sexual orientation, disability, age, marital status, familial/parental status, income derived from a public assistance program, political beliefs, genetic information, veteran’s status, reprisal or retaliation for prior civil rights activity. (Not all prohibited bases apply to all programs.) Oregon State University Extension Service is an AA/EOE/Veterans/Disabled.