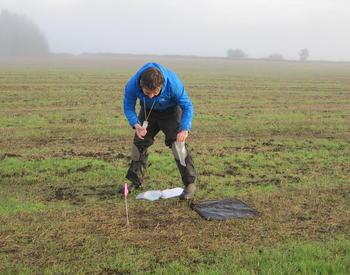

CORVALLIS, Ore. – Jack Lazareck dug some soil out of his garden, swabbed the surface of his hand and sent the samples off to Gwynne Mhuireach for testing.

Lazareck is president of the Multnomah county chapter of the Oregon Master Gardener Association – a nonprofit that enhances and supports the Oregon State University Extension Master Gardener Program. He’s taking part in a community science project to provide the samples that Mhuireach, a postdoctoral researcher at University of Oregon, requires for her research on soil microbes and their transfer to human skin.

When Mhuireach opens the boxes of samples from 40 volunteer Master Gardeners collaborators, she has what she needs to complete a project called “Microbes under your fingernails? Using community science to understand transfer dynamics of soil microbes to humans during gardening.”

“We’re studying whether microbes get on your hands when working in the soil and how it affects the skin microbiome,” Mhuireach said. “Obviously, they do. When you’re in the garden, you’re really in there, down and dirty. But how long do the microbes stick around and what kinds are they?”

The research will inform future studies on how soil affects human health and gives information on the types of microbes living in the soil. Mhuireach assumes she will find some virus that cause disease but assures that the microbes in soil mostly live in harmony with humans.

“Just remember people have been growing things through the entire evolution of humans,” she said. “They would brush it off and eat it. People may be grossed out by the idea of microbes on skin, but in general, the community that lives on our skin and in our gut is incredibly beneficial and helps us maintain good health.”

Lazareck and the other Extension Master Gardener community scientists collected soil samples from their gardens. They swabbed microbial samples off their hands before gardening, immediately after, another 16 to 24 hours later and 24 hours after that. Mhuireach then extracts bacterial DNA from each sample to determine which microbes have transferred to skin.

Gail Langellotto, statewide Master Gardener program coordinator, serves as one of Mhuireach’s project advisors and encouraged the volunteers to participate in the study. She points out that soil health and biodiversity are closely linked to human health but very little is known about interactions between gardeners and soil microbes, even though gardening offers extensive opportunities for such interactions.

“While soil science is well-developed in terms of nutrients and organic matter needed to keep plants healthy, less is known about the diversity and composition of microbes present in soils, particularly in gardens,” she said. “Astonishingly, despite the likelihood of substantial exposure to soil microbes while gardening we lack even the most basic understanding of how much microbial transfer from soil to skin occurs, what types of microorganisms are transferred, or how long they persist. Through this project, we seek to answer these questions.”

Langellotto started the Garden Ecology Lab at OSU and has, with the help of OSU graduate students, undergraduates, and volunteers, studied subjects like pollinators, organic material in garden soils, and native plants.

“We anticipate that this community science project will not only answer our original research questions, but also shed light on how different management practices can impact garden soil health in different climate zones of Oregon,” Mhuireach said. “We will also share our findings with other researchers, farmers/gardeners, and the broader public online and through the Master Gardener network.”

Knowing the microbiome of your soil helps gardeners know the health of their soil, which is important because of all the beneficial things they do like increase soil structure, allowing water and air to move freely and release nutrients as they eat each other.

Lazareck looks forward to the information that will come out of the research. He knows microbial activity is an important factor in effective gardening, but most of the present information is based on hypotheticals. The assumption is that the higher the level of microbes, the more efficient plants are at absorbing nutrients.

Getting soil information drew Lazareck to sign on, but participating as a community scientist is important to him.

“I think it validates my own interest in science,” said Lazareck, a former science teacher. “Research that involves citizen scientists provides data to get meaningful research done and it’s more economically feasible. We provide data that the scientists would not otherwise have.”

Mhuireach agrees. “Community science is a way to engage the broader community in scientific endeavors,” she said. There are more eyes to make valuable observations. It’s mutually beneficial. They learn something and contribute to science.”