Soil is a living ecosystem that includes minerals, air, water, habitat for creatures and the creatures themselves.

Why is soil important?

- Soil provides plants with nutrients, water, physical support and air for roots.

- Soil supplies 14 of 17 essential plant nutrients.

- Soil houses macro- and microorganisms, which are nature’s prime recyclers.

- Soil serves as a reservoir for carbon and plays a vital role in the global carbon cycle.

A typical soil in good condition is composed of approximately 45% mineral matter, 25% air, 25% water and 5% organic matter.

Know your soil

Soils vary across the landscape. The development of a soil reflects the weathering process associated with the dynamic environment in which it has formed. Five soil-forming factors influence the development of a specific soil:

- Parent material.

- Climate.

- Living organisms, or biota.

- Topography.

- Time.

Whenever these five factors are the same on the landscape, the soil will be the same. However, if one or more of the factors varies, the soils differ as well.

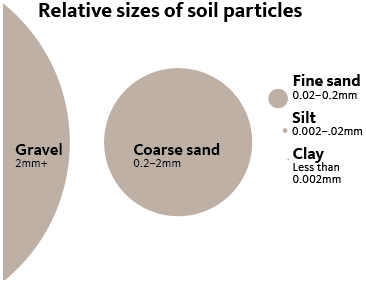

Soil particles

Approximately 45% of soil is made up of mineral matter, or tiny rock fragments. The size of the mineral soil particles varies substantially, from large bits of gravel to microscopic clay fragments. Soil mineral particles are classified based on their size.

Clay particles are so small that you would need a powerful microscope to see them.

Soil texture

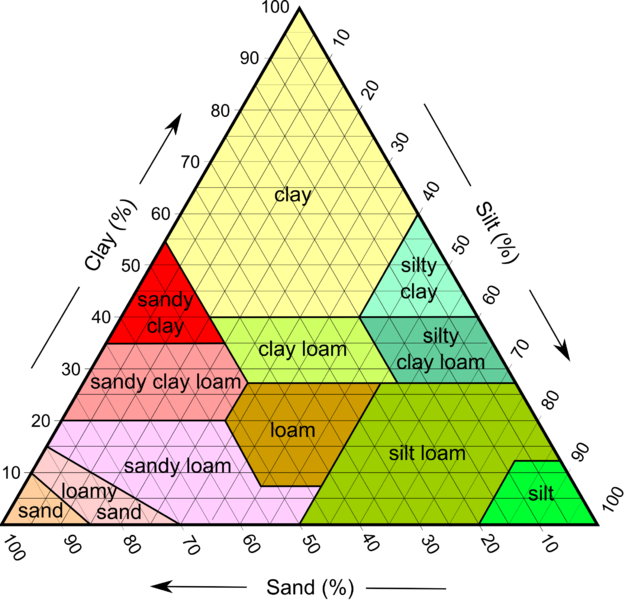

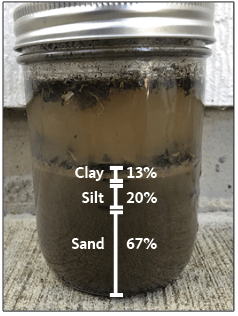

Soil texture is determined by the ratio of sand, silt and clay particles, which gives soil its look and feel.

A simple test lets us measure the ratios of sand, silt and clay in a soil. Once these ratios are known, you can use the Soil Texture Triangle to identify the texture of the sample.

Soil structure

Soil structure describes the size, shape and friability (or crumbliness) of the aggregates that form a soil. The aggregates are formed from sand, silt, clay and organic material bound together with mineral and organic cements. The crevices and spaces in and between the soil aggregates are important habitat for soil biota. They also are critical for holding moisture. While soil texture cannot be easily changed, soil structure can be improved through good management practices.

Stable soil aggregates are the underpinnings of a healthy soil habitat. Here, fungal hyphae, organic matter and mineral and organic cements known as glomalin hold mineral particles together.

Soil aggregates that hold together, even when wet, are critical to good soil structure.

Classifying soils

The Natural Resources Conservation Service of the U.S. Department of Agriculture has identified and mapped soils for most of the U.S. Each of these soils is defined by the texture and horizons that compose the soil and is referred to as a soil series. Many of these soil series are named for a town or feature near where the soil was first identified. Each state in the U.S. has a state soil series, just as states have official state birds and flowers.

Check out a soil map

Find maps and descriptions of local soil series in county soil surveys. The online tool Web Soil Survey is the most up-to-date place to find soil maps and soil survey information.

The soil survey includes valuable information about each soil series. This includes the potential uses of the soil (for agriculture, grazing, forestry, building foundations, septic drain fields); limitations, such as erosion potential or poor drainage; and productivity for agriculture or forestry uses. You can learn a lot about potential uses of your land by learning what soil types you have and their uses, limitations and productivity.

You can quickly generate a soil map of an area by entering the address or site coordinates on the Web Soil Survey page or on a mobile app. In addition to a map showing the names of the soils, you will see a description of soil textures and slope in a table. Clicking on the highlighted soil name in the table generates a more thorough description of each soil.

- Try mapping the soils on your property.

- Watch a video demonstration

- Try this step-by-step guide to the Web Soil Survey

Conduct at-home soil assessments

A soil texture jar test will tell you the proportions of sand, silt and clay in the soil on your property.

Follow instructions from a University of California Agriculture and Natural Resources handout.

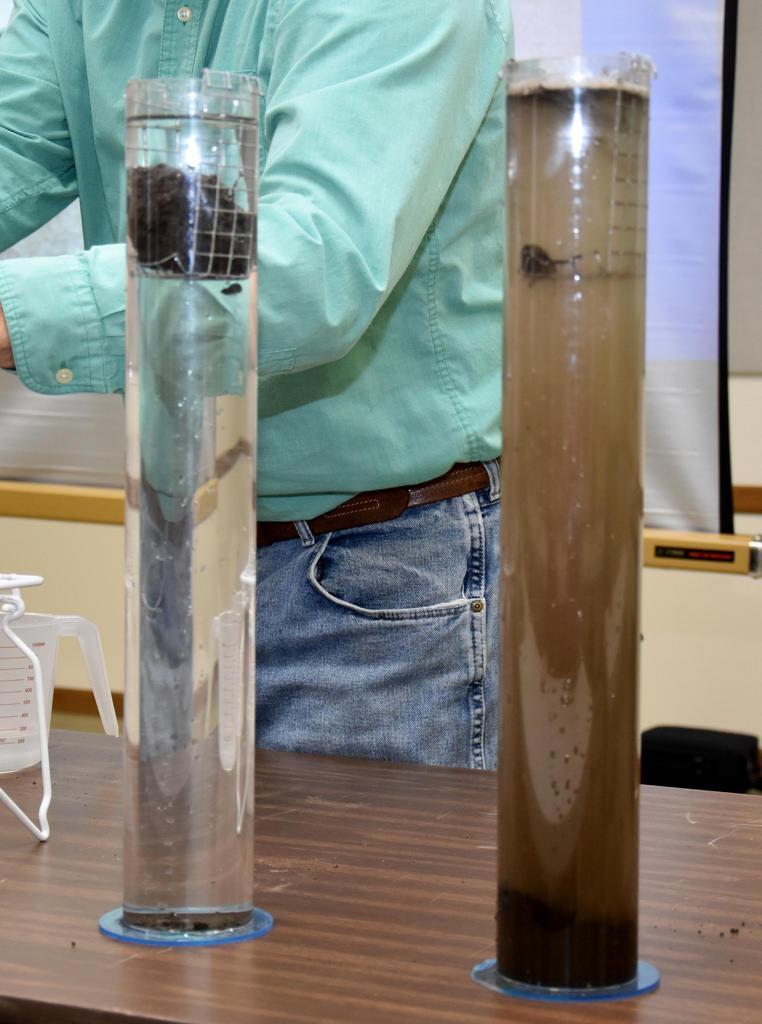

A slake test, where soil clods are saturated in water, will tell you about your soil’s structure and aggregate stability. Stable aggregates, those which do not dissolve when wet, are key to healthy soil. Ray Archuleta, a conservation agronomist at the NRCS, describes this test in a USDA video.

Test your soil fertility

While test kits can allow you to evaluate your soil’s chemical properties at home, send a soil sample off to a commercial laboratory for the most accurate results. Routine soil tests will evaluate the soil’s pH or acidity and measure the phosphorus, potassium, calcium, magnesium and organic matter content. These are key factors in growing healthy and productive plants in your garden, lawn or crop field.

Collect a representative soil sample from the areas of your property in which you’re interested. See A Guide to Collecting Soil Samples for Farms and Gardens.

Many commercial laboratories and universities perform routine soil fertility testing.

- In Oregon, see Analytical Labs Serving Oregon, EM 8677

- Labs serving Washington

- Labs serving California

Testing labs can provide recommendations of fertilizers and amendments needed to grow various plants or crops. Your local Extension agent can help interpret results. Or, consult the Soil Test Interpretation Guide, listed in “Resources.”

Many testing laboratories offer soil health assessments and tests for soil contaminants like pesticides and heavy metals. If you think you’re a candidate for these tests, contact a testing laboratory or your local Extension office.

Management practices to build healthy soil

The Natural Resources Conservation Service defines soil health or soil quality “as the continued capacity of soil to function as a vital living ecosystem that sustains plants, animals and humans.” What soil health strategies you use depend on the soil type and your management goals.

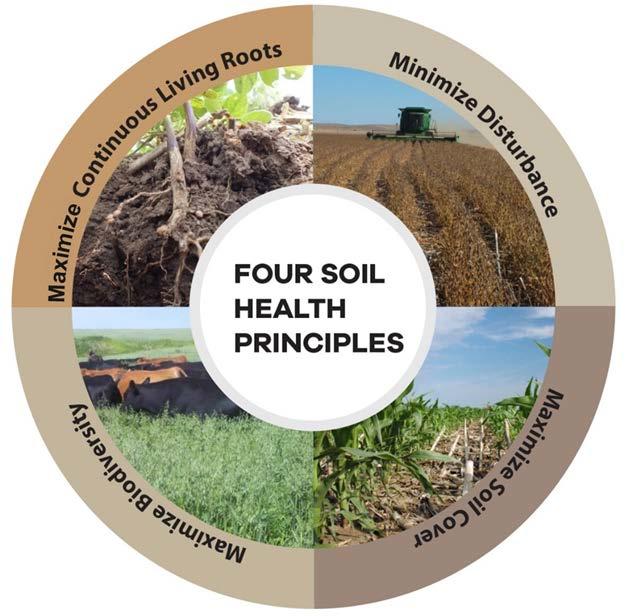

Limiting physical disturbance and enhancing organic matter in the soil are key to soil health. NRCS has developed four principles of soil health to implement on your property:

- Maximize continuous living roots.

- Minimize disturbance.

- Maximize soil cover.

- Maximize biodiversity.

Minimize disturbance

Tillage, the mixing or cultivation of soil to control weeds or prepare a seedbed, is detrimental to healthy soils. The physical disturbance caused by tillage breaks up soil aggregates, which can reduce water infiltration, limit root penetration and cause the soil to crust. Tillage can kill soil macroinvertebrates and reduce the presence of beneficial fungi such as mycorrhizae. Tillage breaks open soil aggregates, exposing organic matter to oxygen and microorganisms, which hastens decomposition and loss of carbon from soil. While tillage improves the tilth or workability of soil in the short term, tillage degrades the soil structure over the long term. Protect the soil ecosystem by developing a management plan that minimizes soil disturbance.

- Plant perennial crops and landscape plants that can grow for many years between tillage events.

- Sell your rototiller. Aggressive mixing by rototillers damages soil structure — more so than many other tillage implements.

- Control weeds prior to planting with techniques like solarization or occulation, which involve covering the ground with plastic for a period of time.

- Use “lasagna composting” to develop a vegetable or flower garden.

- Implement organic no-till practices, using cover crops and a roller or crimper.

- Consider low-risk herbicides rather than tillage to control weeds and unwanted vegetation while protecting soil structure.

Limit compaction

Limiting compaction is vital to maintaining soil pore space for gas exchange and water infiltration. Working soil while it is wet is a major cause of compaction because of the pressure exerted by tractor and truck tires. Livestock on wet soil also cause compaction, sometimes called “pugging.”

Limit compaction by:

- Limiting tillage, especially when soil is wet.

- Avoiding driving over wet soil. Build lanes or roads if driving is required.

- Improving load distribution across the soils; vehicles with tracks or flotation tires limit compaction.

- Planting a perennial cover crop, such as turfgrass or white clover, in pathways that receive foot or tractor traffic.

- Improving drainage to ensure soils are adequately dry when worked. Cover crops can help soils dry more quickly in spring.

- Planting deep-rooted cover crops such as daikon radish, and adding organic matter to alleviate compaction.

Remember that deep-ripping or tillage usually provides a short-term fix to compaction problems. Don’t plan to rely on tillage to fix compaction caused by poor management practices.

Maximize soil cover

Prevent erosion and build soil health by maintaining a layer of physical protection, either as a living plant or mulch. Most erosion is initiated by the impact of raindrops onto bare soil. The splash caused by raindrops or irrigation detaches soil particles from aggregates and allows them to be moved by water.

Tips for soil cover

- Plant cover crops or grass sod to keep the soil covered year-round.

- Leave crop residues in place to armor the soil.

- Use mulch to prevent weeds and keep soil covered.

Some soils have the propensity to form crusts. When raindrops impact the soil and break down aggregates, the clay and silt particles wash into soil pores and create a crust upon drying. These crusts can prevent seedlings from emerging, decrease water infiltration, and increase erosion.

Prevent crust formation

- Limit tillage and amend the soil with organic matter to promote aggregation.

- Keep the soil covered with living plants or mulch to limit the breakdown of aggregates by the direct impact of raindrops.

Maximize continuous living roots

Living plants are the major food source for soil organisms. Many people don’t appreciate how “leaky” roots are. Roots can exude 10%–40% of the sugars made during photosynthesis, providing an important source of food for soil microbes. This process is called “rhizodeposition.” Roots also continually slough off cells, which microorganisms decompose.

There are also examples of direct partnership or symbiosis between plants and soil microbes. Two examples include the Rhizobium bacteria, which fix nitrogen symbiotically with legumes, and the mycorrhizal fungi, which help to transport phosphorus and water to plants. Maintain growing plants and roots for as much of the year as possible to ensure an active and functioning soil food web.

- Use perennial crops, cover crops and tight crop rotations to maximize the presence of living roots throughout the year.

- Consider living mulches for weed control.

- Pasture and perennial forages provide continuous cover and living roots for as much of the growing season as possible. Consider adding pasture or forage crops to your crop or garden rotation.

Maximize biodiversity

Biodiversity is the range of living organisms on your property and in your soil. It includes plants, animals (including livestock), insects and microorganisms. Increased diversity has been shown to make natural systems more resilient to change. Crop rotations reduce disease and insect pressure compared with monocropping. Diverse species mixtures in pastures and hayfields improve the stability of yield from year to year, and alfalfa, clover and other legumes contribute nitrogen to grass species. Studies have shown that increased plant diversity can increase the diversity and function of soil fauna and microbes.

Promote biodiversity in your soil

Diverse cover crops in farm fields and home gardens often include different species of grasses, legumes and brassicas.

- Implement a diverse crop rotation in your garden or farm fields

- Explore intercropping, silvopasture and agroforestry practices.

- Plant a “cocktail” of cover crop species in the off-season or between crops.

- Plant diverse hedgerows and buffer strips to support insect and wildlife diversity, limit erosion and protect water quality.

- Incorporate the use of livestock on your property to utilize “waste” products and improve nutrient cycling. Remember that those cover crops can make great forage for livestock.

Establish goals for your soil

The health and quality of your soil determine the potential of everything growing on your property. Your goals may vary. You may want to protect and improve soil health in your forest, pasture, farm and garden. You may want to prevent soil from eroding in all of these situations and keep it from contaminating your stream and waterways. Each of these situations calls for different strategies. You may have some soil goals under other categories. Keep soil goals in mind as you formulate overall goals for your property. Here are a few examples of agriculturally oriented soil goals to spark your thinking:

- Learn about the soil you have. Get your soil tested. Make a soil map.

- Learn more about holistic approaches to soil stewardship that support healthy and fertile soil.

- Implement no-till agricultural practices, or minimize tillage frequency and severity where possible.

- Make a plan to rehabilitate an area where soil is compacted.

- Keep soil covered using cover crops and mulches.

- Measure your soil organic matter and work to increase it.

- Enjoy your soil! Get some dirt under your fingernails.

Resources

Agroforestry for Ecosystem Services and Environmental Benefits, The Center for Agroforestry

Analytical Laboratories Serving Oregon, EM 8677

Building Soils for Better Crops: Sustainable Soil Management, Sustainable Agriculture Research and Education

Conservation Buffers: Design Guidelines for Buffers, Corridors, and Greenways, General Technical Report SRS-109 U.S. Department of Agriculture, U.S. Forest Service

Cover Crop Innovators Video Series, Sustainable Agriculture Research and Education

Cover Crops for Soil Health Workshop, SARE

Crop Rotation on Organic Farms, SARE

Does Glomulin Hold Your Farm Together?, USDA Agricultural Research Service

The Five Factors of Soil Formation, Virtual Soil Science Learning Resources

A Guide to Collecting Soil Samples for Farms and Gardens, EC 628

Integrating Livestock and Crops: Improving Soil, Solving Problems, Increasing Income, ATTRA — Sustainable Agriculture Program

Living Mulch Builds Profits, Soil, American Society of Agronomy

Managing Cover Crops Profitably, SARE

No-Till Cover Crop Roller, Rodale Institute

Rototill Sparingly, University of Maryland Extension

Sheet mulching — aka lasagna composting — builds soil, saves time, OSU Extension Service

Silvopasture: An Agroforestry Practice, EM 8989,

Soil Food Web, Natural Resources Conservation Service

Soil Health, NRCS

© 2020 Oregon State University.