Growing Farms Online Course: Learn how to start a successful sustainable small farm.

Developed by OSU Small Farms Program faculty and other farm management experts, you will learn the essentials of designing and growing your own thriving farm business. And the entire program is available online, so you can complete it on your time, around your schedule. Turn your dream of owning and operating a small farm or ranch into a successful reality with this popular program!

An overview

Beef production is a large and important segment of American agriculture and one of the largest industries in the world. Beef enterprises work well with grain, orchard, vegetable, or other crop operations. Cattle can make efficient use of feed resources that have little alternative use, such as crop residues, marginal cropland, untillable land, or rangeland that cannot produce crops other than forage.

For people who own land but work full-time off the farm, a beef enterprise can be the least labor-intensive way to utilize their land. Calving, weaning, vaccinating, and weighing can be planned around times when labor is available.

Consider your resources, finances, level of interest, and the land available before deciding to engage in a beef enterprise. Identify why you want to raise cattle and if your land is suited for it. Set goals to achieve the most constant economic return or personal satisfaction. Your goals must be clearly defined, firmly fixed, achievable, measurable, and have a realistic time frame. Otherwise, your operation will lack meaning, objective, and focus.

This publication will cover some of the basics of various beef enterprises, including production, management, health, and marketing. It also includes “Cow Talk,” a helpful glossary of terms used in the cattle industry.

Choosing a beef production strategy

Production options

There are several types of small-scale cattle enterprises. Generally, they are grouped into three broad categories:

- Cow-calf breeding herd—Cows produce calves that either are sold as breeding stock or feeder animals, or are fed to harvest weight and then sold to processors or consumers. A breeding operation may require a combination of marketing methods.

- Growing and feeding operation—Calves or yearlings are purchased, raised to harvest weight, then sold.

- Backgrounding operation—Weaned calves are purchased and raised for entry into a feedlot or other type of finishing operation.

The success of your operation depends on adopting a strategy that fits your needs. After reviewing this publication and generating some ideas about what kind of operation you would like to have, contact your county or regional Extension professional to develop a detailed plan.

Cow-calf breeding herd

Establishing a breeding herd takes time. It also requires more land than a simple cattle growing program. Consider whether your available resources match your long-term objectives. There must be adequate feed, water, and fences to accommodate a year-round operation. Land and facilities may be available for rent nearby.

Decide whether to have registered purebred cattle or commercial cattle. The main source of income from registered cattle is the sale of breeding stock, whereas the main source of income from a commercial beef herd is the sale of calves for finishing, and old or cull animals for processing. Care, management, and marketing of registered cattle is also more intensive than for commercial cattle.

Managing a cow-calf herd

The major objective of most cattle producers is profit. For a cow-calf herd, profits are determined by the percent calf crop (the number of calves weaned per cows exposed for breeding the previous year), the weaning weight of the calves, the costs of maintaining breeding animals, and, ultimately, the sale price of the calves.

Because your entire program depends on the fitness of the breeding animals, it is essential to maintain good herd health by not allowing the cattle to become too fat or too thin. Overweight or underweight cows do not milk as well and may have problems calving or getting bred. Bulls in poor condition may not perform well during the breeding season. Information on nutritional needs of beef cattle can be found later in this publication.

Developing a registered herd

If your objective is to raise registered cattle and supply breeding animals to other cattle producers, it may be necessary to invest large amounts of capital in purebred stock. In a registered herd, both the sire and dam must be purebred and registered with the same national breed association. You must keep accurate records and register the desirable purebred calves that will be retained for breeding stock or sold to other producers.

If you want to raise bulls for the beef industry, you must select cows and bulls based on characteristics of economic importance, such as fertility, mothering ability, ease of calving, growth rate, and carcass merit. Also, use great care when selecting breeding females, as it involves considerable time and expense.

The purebred market is very competitive due to already established herds. However, it is possible to have a successful registered herd with only 30 to 50 cattle.

Developing a commercial herd

The criteria for selecting good commercial cows are appropriate size, quality, age, condition, stage of pregnancy, and market price. You should select breed and cow size to match your feed resources, environment, and topography. Local ranchers or Extension personnel can give you an idea of what breeds are best suited to your area. Crossbreeding (mating animals from two or more breeds) can be an advantage in a commercial cow herd. Capitalizing on the merits of several breeds, plus the extra vigor from crossbred calves, may give you a competitive edge in the market. However, advances in genetic merit probably will not be realized for several years.

Purchasing cattle

There are many sources of good cattle, both registered and commercial. Usually, it’s best to purchase from a successful and reputable breeder. They typically sell only sound cattle as breeding animals, and can offer advice to less experienced producers. If you are inexperienced, it might be best to go to one source and buy good, young, bred cows that have calved at least once. This reduces problems associated with calving heifers. Also, a single source reduces the risk of disease that can occur when co-mingling cattle from various sources. If you purchase open heifers, you should breed them to a bull that has the genes for easy calving.

Breeding (mating)

It is ideal to have a controlled breeding season, rather than allowing bulls to run with cows continuously. A 45- to 60-day breeding season is recommended. The resulting shortened calving season increases the chance of having a uniform set of calves to sell at market time. Cattle of similar breeding and size usually bring more money. Another advantage is you can condense the period of time you spend working with cows during calving instead of stringing it out for months.

Cattle have a 283-day gestation period, plus or minus 19 days. Select breeding dates so cows will calve at the time of year you desire. Factors when determining calving season include weather conditions, your ability to match feed resources with the cows’ requirements, availability of labor at calving time, and market considerations. Oregon has a diverse climate, with the east side being dry and the west side having higher rainfall. Higher rainfall areas present a challenge to cow-calf production.

For example, seasonal considerations for western Oregon may include the following:

- Late-fall/winter calving is usually not desirable because rain causes wet, muddy lots and pastures. The adverse weather may increase the incidence of calf scours and pneumonia. Having a covered calving facility, though, helps decrease some of these issues.

- Late-summer/fall calving is a common practice because of ideal weather. However, you must feed a high-quality ration to nursing cows and calves during winter, when only harvested feeds are available. This greatly increases feed costs.

- Late-winter/spring calving allows cows to feed on rapidly growing range and pasture, thus eliminating harvesting costs. Later-born spring calves may be too young to use all the milk the cow provides as a result of the excellent nutrition she is receiving.

A quality bull is essential to maintain a good, healthy herd. The general ratio is 1 bull to 25 cows. This varies depending on pasture size and the bull’s age and health.

Small-herd owners have the following options for obtaining a quality bull:

- Buy a virgin bull for dedicated use on a single farm or ranch.

- Buy a bull in cooperation with another ranch.

- Lease a bull from a reputable breeder, provided the breeder gives evidence the bull is free from sexually transmitted diseases such as trichomoniasis and vibriosis.

Using a co-owned or leased bull increases the risk of disease. Bulls also pose a safety risk, so handle them carefully.

Another good breeding option is artificial insemination (AI). Often, faster and more dependable genetic improvement can be made through AI. If you use this method, synchronizing estrus in the herd is encouraged. Consult your veterinarian to develop a synchronization protocol most likely to achieve your goals.

The last consideration of the breeding season is pregnancy testing cows. The test helps determine which cows should be culled from the herd to avoid the costs of feeding a cow that is not pregnant. Veterinarians offer pregnancy testing services, and pregnancy testing via blood samples is now an affordable option as well.

Calving

This aspect of beef cattle management requires experience and skill. If you are inexperienced, contact your veterinarian or Extension professional for advice on calving management. Personal safety should always be a priority when working with cows and bulls, especially with cows at calving time.

After a calf is safely delivered, it is important that it consume colostrum from the mother within a few hours. The goal is for a calf to receive 10 percent of its body weight in colostrum within 4 hours of birth, and a total of 20 percent of its body weight in colostrum within 24 hours.

Colostrum supplements and replacers are available to augment and replace, respectively, colostrum of low quality or quantity. These commercial products are safer than colostrum borrowed from another farm because they will not transmit diseases. It is best to use colostrum replacers, not supplements. Colostrum supplements contain less than 100 grams of immunoglobulins per dose and may even interfere with the uptake of immunoglobulins in the dam’s colostrum. If using colostrum replacer, give a calf 150 to 200 grams of immunoglobulins within 4 hours of birth.

Excess colostrum can be harvested from docile cows and frozen for use as needed within one year. Thaw frozen colostrum in warm water, not a microwave. Your veterinarian or Extension professional can instruct you on the importance of colostrum, how to stockpile colostrum or replacer, and how to administer it when needed.

Rebreeding

Cows are usually exposed to bulls again or artificially inseminated starting about 2 months after calving. Two months is typically enough time for a cow’s uterus to return to normal and for her to start cycling again. Individuals that had difficulty calving, retained placentas, uterine infections, or poor body condition will need special attention to prepare them for rebreeding on time. Getting cows bred within 3 months of calving is essential to keep the cow herd calving once every 12 months and keep calves uniform in size and development. The average beef cow will nurse a calf for about 2 months, then become pregnant again with her next calf while nursing her current calf for about 5 or 6 more months.

Working calves

One of the simplest ways to add to the value of your calves is to make sure they are well fed, castrated, dehorned, vaccinated, and clearly identified. The most important thing to remember when working calves is to stress them as little as possible. You can learn how to castrate, dehorn, and give vaccinations under the supervision of an experienced cattle producer. Veterinarians will also perform these procedures for a fee. An effective vaccination program is vital to herd health and performance. Your Extension professional and veterinarian are good sources of information on this subject.

Weaning

Weaning is accomplished by separating calves from their mothers. Calves should be weaned at approximately 7 to 8 months of age. This gives the cow time to regain body condition necessary for adequate calving performance when she calves again in 3 or 4 months. Calves need an ample supply of fresh water and feed. Some producers prefer to creep feed (feed calves in an enclosure accessible only to them) prior to weaning. This may help calves gain weight more quickly and begin eating more readily from a feed bunk after weaning.

Fenceline weaning is a management system in which calves are separated from cows by a fence, but can still see, hear, and smell their mothers. Depending on the fencing used, physical contact may also be possible. Electric fencing, consisting of a couple of hot wires, is recommended to prevent permanent fence damage from animal pairs trying to reunite. The fenceline weaning method may reduce stress related to transport and environmental, dietary, and social changes.

Keeping performance records

Keeping records enables you to cull poor performers and maintain good overall herd health and vigor. Examples of helpful calf records include birth weight, weaning weight, and average daily gain. Your Extension professional is a good resource for help with records.

Options for calves

Most calves produced in small commercial herds are marketed as weaned calves. Other options include, but are not limited to:

- Wean calves, winter them, and sell them as yearlings.

- Creep feed calves while still nursing, put them on full feed after weaning, and then sell them as slaughter cattle at 14 to 16 months of age.

- Wean calves, place them on a growing ration during the winter, and then allow them to graze during spring and early summer. Finish on either a concentrate ration or forage until they reach harvest weight at approximately 18 to 24 months of age.

Growing and feeding operation

In this type of operation, you purchase calves after weaning at approximately 7 months of age. They can be marketed in less than a year from the time of purchase, so the investment on each calf is returned within a comparatively short time. This type of operation may not require much land, but adequate facilities are essential so animals can be kept comfortable and under control. For more information on developing a growing and feeding operation, refer to the facilities, feeding, and health sections of this publication. Profitability is variable and depends on purchase price; feed, labor, and facilities costs; health; and selling price.

Backgrounding or stocker operation

A backgrounding or stocker operation typically pastures or feeds purchased weaned calves until they reach 750 to 800 pounds. Then they are sold to a feedlot for finishing. Some excellent enterprises are solely pasture operations. Weaned calves or yearlings are purchased in early spring, go on pasture when the grass is ready, and are sold when the pasture season is over. On the other hand, calves cost less in the fall; so, depending on the cost of winter feed and facilities, fall may be the best time to purchase cattle for the next pasture season.

Similar to a growing and feeding operation, profitability in this type of enterprise is greatly influenced by purchase price, rate of gain, and selling price. Ask an Extension professional or experienced beef cattle person for advice on purchasing animals that best suit your type of operation, land, and resources.

Managing newly purchased calves

When you purchase calves for any type of enterprise, keep them isolated in an area that allows you to observe them closely for at least three weeks. This enables you to reduce the spread of disease to other cattle on the farm. Calves should have access to plenty of fresh, clean water and high quality feed. Working the calves requires a lot of patience, because they are easily excited and stressed. Your veterinarian or Extension professional can help you develop a receiving program that lowers the risk of disease and nutritional issues for purchased calves. This is an important part of a biosecurity plan discussed later in this publication.

Facilities and equipment

Producing beef cattle on a small farm does not require elaborate or expensive housing or facilities. Under most weather conditions, cattle do very well outside.

In the Pacific Northwest, cows need a mud-free area with protection from wind and rain. One method is to allow animals access to a three-sided shelter. In a fully enclosed building, proper ventilation is critical to maintain good health.

Design facilities to make your job easy, efficient, and safe. An effective working facility consists of a corral with a narrow alley and a squeeze chute. The chute is needed to restrain animals for vaccinations, pregnancy checking, deworming, etc. The corral and narrow alley help confine animals that need to be handled and driven into the chute or head catch. Well-designed handling facilities help minimize animal confusion and stress. Poorly designed facilities increase stress on animals and may cause injuries and poor performance, which can affect meat quality. Use of electric prods is not recommended because they cause unnecessary pain and stress on animals. Good facilities reduce the risk of injury to both animals and people.

It is important to maintain the quality of feed. Store forages (including hay, straw, or silage) and grains in a dry building protected from rodents and birds. Forages lose nutritional value when exposed to direct sunlight. Wet hay loses feed value and palatability and presents a safety hazard due to risk of combustion or mold or both. Rodents can damage feed and spread disease.

Feeders (bunks or other devices from which cattle eat) are preferable to feeding cattle on the ground. They reduce feed waste and prevent the spread of many internal parasites and other cattle diseases. Many kinds of feeders are commercially available. You can also purchase supplies to build your own feeders.

An adequate, year-round supply of water is essential to any successful cattle enterprise. Many types of water troughs are available from local feed or farm supply stores. You can recycle old barrels, tractor tires, and bathtubs to make functional troughs; just be sure to clean them thoroughly prior to use and regularly thereafter. Do not use barrels and containers that held chemicals or hazardous materials.

Pens, feedlots, and corrals should be located at a convenient distance from feed storage facilities. These areas should be well drained, with the drainage moving away from feed storage, working facilities, and roads. It is important to make these areas accessible to tractors for easy feeding and cleaning. It is also important to make sure manure and other contaminated runoff does not enter streams, roadside ditches, or other waterways. A well-designed manure management system can help prevent water quality issues. In high-rainfall areas, gutters on buildings are essential to direct clean water away from livestock lots. This can also help reduce the amount of mud around buildings and feeding areas.

Good fencing is very important to keep beef cattle contained. The property perimeter fence needs to have strong corner braces and adequate height to keep larger animals from breaking it down or jumping over it. Electric fences can be used for dividing interior paddocks or lots. In closed range areas, you are responsible for property damage if cattle get out; a farm liability insurance policy is recommended.

Proper transportation for your cattle is a must. A 1-ton or ¾-ton truck and livestock trailer are recommended for any beef operation. A truck or flatbed trailer also is useful for transporting and dispersing hay.

Feeding beef cattle

Cattle have a ruminant digestive system. Their stomachs are made up of four parts. Ruminant microorganisms in the first three parts enable cattle to digest fibrous feeds that humans cannot. This microbial breakdown produces essential nutrients such as amino acids and B vitamins, making beef beneficial for human consumption.

Nutritional needs

Cattle require protein, energy, water, fat, minerals, and vitamins in their diet. The amounts vary according to environment, time of year, production goals, and the animal’s age, weight, and reproductive stage. Availability of feedstuffs also varies by location and season. Feed is generally 75 percent of the cost of raising an animal.

Protein and carbohydrate levels adequate for growth and maintenance are normally found in high-quality legume hay, such as alfalfa and clover. Poor-quality feeds, such as cereal straw, grass straw, or rain-damaged hay, require protein and energy supplements to meet cattle nutritional needs. High-quality hay can also be used to supplement poor-quality forages.

Forage analysis should be conducted on each load of hay to determine its nutritional value and balance rations properly. Ask your Extension professional how to take a sample and where to get it analyzed.

Beef cattle normally do not need vitamin A, B, C, or E supplementation. They can get these vitamins from their rumen microbes and normal-quality feedstuffs. However, a vitamin A deficiency can result from feeding on dry, bleached-out hay. Signs of vitamin A deficiency include watery eyes, rough hair coat, night blindness, and poor gains.

Vitamin D is formed by exposure to sunlight. If you confine your cattle to a barn or stall for extended periods of time, vitamin D deficiency may become a problem.

Minerals are inorganic compounds that contribute to bones, teeth, protein, and lipid functions of the body. Minerals are provided through natural feeds and supplementation.

There are three main categories of mineral supplements:

- Salt, usually sold as iodized salt, which only contains sodium, chloride, and iodine

- Trace mineralized salt, which consists of a large percentage of salt and traces of some or all of the following: copper, iron, iodine, cobalt, manganese, selenium, and zinc

- Mineral mixes, which usually contain major minerals such as calcium and phosphorus, as well as trace minerals and some salt; for selenium-deficient areas, selenium is an important component of trace-mineralized salt and mineral mixes

You can provide mineral supplements free choice or mix them into feed. The composition of needed salt or mineral supplements varies depending on your locale and feedstuffs.

Clean water is essential and must be provided at all times. Under normal conditions, cattle consume 4 to 20 gallons of water per day depending on size, age, and weather. High environmental temperatures dramatically increase water consumption.

The adequacy of a nutritional program can be monitored by animal health, body condition scores, rate of gain, reproductive efficiency, and absence of specific nutrient deficiency signs.

Types of feed

Feedstuffs are categorized as concentrates or roughages. Concentrates are feedstuffs high in digestible nutrients, like grains and protein supplements. Roughages are feedstuffs that usually have a lower nutrient density and more fiber. Examples of roughages include hay, pasture, and silage.

As a general rule, beef cattle consume up to 3 percent of bodyweight of good-quality feed (on a dry matter basis) per day. For example, a 500-pound weaned calf could eat 17.6 pounds of high-quality alfalfa hay (which equals 15 pounds on a dry matter basis) per day. The percent of bodyweight intake is much lower for poor-quality roughage and coarse feeds. Mature grass hay, for example, could result in an intake of 1.5 percent of bodyweight and lead to nutritional deficiencies.

The percentage of roughage and concentrate in beef cattle rations depends on the type of animal being fed. For example, feedlot steers are fed mostly grain and a little roughage, while bred cows may be wintered on good-quality roughage alone. Caution: high-quality legume hay such as alfalfa may cause bloat.

There are several types of finishing operations, but they fall into two major categories: feedlot (grain-fed) or forage-finished. Feedlot cattle usually weigh 700 to 800 pounds before they are placed on a high-grain (high-energy) diet. This diet is fed until they achieve harvest weight. If you feed to harvest, you can purchase feed or grow and mix it at home. If only a few animals are being finished, it may be more economical to purchase the mixed diet from a feed dealer.

Beef cattle that are forage- or pasture-finished are fed either conserved forage (silage or hay) or grazed to harvest weight, or a combination of the two. Forage-finished cattle typically take longer to reach harvest weight and quality. Despite that, the cost per pound of gain could be less than grain-fed animals.

Growth promotants, including anabolic steroids (implants), may have a place in your operation. They are used widely in the industry and have been proven safe. Ionophores are feed additives that decrease rumen upset, increase feed efficiency, and increase daily gains. These chemicals can improve gain significantly; however, they do not compensate for poor management.

Organic, natural, and grass-fed operations usually avoid the use of growth promotants. It is important to understand the desires of the product’s end consumer when developing a feed program for your beef operation.

Keeping your cattle healthy

Cattle of all ages—but particularly young, growing cattle—are subject to a variety of ailments. They range from mild conditions to severe infectious diseases that may cause death quickly.

The cost of caring for sick cattle can seriously reduce your profit margin. With the increasing need to cut production costs, good herd health care is very important for any beef operation.

Prevention is the easiest and cheapest method of disease control. Clean sheds, lots, and feed and water troughs give disease less chance to get started. A sound vaccination program, parasite control, and frequent observation of the herd also help reduce the occurrence of illness.

You can recognize a sick animal first by its abnormal behavior or physical appearance. Droopy ears, loss of appetite, lowered head, scouring (diarrhea), or inactivity may indicate illness. A high temperature (greater than 102.5°F) can also indicate disease.

The best course of action is to find a sick animal quickly, treat it, and then work to eliminate the cause of the sickness. If an animal has a contagious disease, the rest of the herd has been or will be exposed to it.

Health problems are more common during and after periods of stress, including calving, weaning, shipping, working or moving the cattle, poor nutrition, mud, and extreme weather conditions. Stress will reduce an animal’s ability to resist infection. After a period of stress, give extra attention to your animals’ health.

Common cattle diseases

The following are important disease considerations for a beef herd health program. You also need to be aware of other diseases that affect the health of livestock in your region. Vaccinations and parasite controls are available for many of the conditions affecting cattle. The choice of remedy and time of application depend on a variety of things, including the animal’s nutritional level, disease prevalence in the herd, and the region in which the cattle are located. A good relationship with a large-animal veterinarian in your area is desirable for planning an effective disease prevention program and staying informed about local beef health concerns.

Respiratory diseases

Respiratory diseases are common in cattle. A number of factors contribute to an outbreak: inadequate nutrition, stress, overcrowding, poor ventilation, and viruses or bacteria. Good management and vaccination of cows and calves is the best way to prevent outbreaks of respiratory disease. Effective ventilation systems are critical to maintain air quality for housed animals. Your veterinarian can help you develop a program to reduce losses on your ranch and in the feedlot.

Clostridial diseases

Clostridial organisms are present in the environment and can cause disease when they gain access to the body through the mouth, broken skin, or other damaged tissues and release their toxins. Intensive treatment can overcome clostridial disease in some animals if the disease is diagnosed early.

Clostridial disease can progress rapidly and often there are no clinical signs observable before the death of the affected animals. A vaccination program is the best control method. Such a program requires a 7- or 8-way vaccination every 6 to 12 months, depending on veterinary recommendations. Pregnant cattle should be boostered in the last month of pregnancy to ensure adequate protective antibodies in colostrum for passive immunity for calves.

Clostridial bacterin vaccination is recommended for all calves. To be effective, booster doses should be given 3 to 6 weeks after the first injection at 2 to 3 months and again at 6 months of age. Be sure the vaccine used includes protection for C. tetani so bull calves will be protected against tetanus after castration.

White muscle disease

White muscle disease is a serious problem in many areas of the Pacific Northwest due to low levels of selenium in soils. Lack of adequate selenium in the diet can cause degeneration of skeletal and cardiac muscles, causing weakness, respiratory distress, and even death.

If you are in an area where white muscle disease is likely to occur, be sure to supply adult animals with adequate amounts of selenium in the diet via feed, mineral mixes, and/or by fertilization (in Oregon). Most calves will need a selenium injection at birth and maybe also a month later to meet their dietary needs.

Monitor the selenium status of adult cattle to determine if additional supplementation is needed, including selenium injections during the last month of pregnancy. Consult with a veterinarian about supplemental selenium during pregnancy. Selenium status can be monitored via blood samples from live animals or liver samples from harvested animals. A detailed discussion of selenium supplementation can be found in Selenium Supplementation Strategies for Livestock in Oregon (EM 9094). Do not over supply selenium because it can be toxic.

Brucellosis (Bang’s disease)

Brucellosis (Bang’s disease) is a serious disease that causes abortion and sterility in cattle, bison, elk, and deer, and undulant fever in humans.

Federal and state laws effectively outline brucellosis control. Vaccination is required for all breeding heifers.

Brucellosis most commonly enters a herd through the purchase of infected cattle. To help prevent brucellosis from entering your herd, have a veterinarian vaccinate all heifers when they are between 4 to 10 months of age, and purchase only brucellosis-vaccinated cattle.

In Oregon, cattle older than 12 months can also be vaccinated and are called “mature vaccinates.” Stipulations apply, so discuss with your veterinarian.

Bovine viral diarrhea virus

The bovine viral diarrhea (BVD) virus can cause a multitude of problems in cattle including respiratory disease, abortions, fetal malformations, and persistently infected (BVD-PI) animals. If pregnant cows are infected mid-pregnancy with a viral strain to which they have no immunity, their calf may become BVD-PI: a life-long viral shedder and source of infection for herdmates. Individuals can be checked for BVD-PI status through ear notch testing; positive animals, their dams, and their offspring should be culled at once. All herd additions should be tested before entry. There are numerous cattle vaccines to protect against BVD. Work with a veterinarian regarding the type to use for your operation and when to use it.

Johne’s disease

Johne’s (“YO-neez”) disease is caused by a bacterium that can affect all ruminants. It causes a chronic infection of the intestinal tract that eventually becomes severe enough to cause extreme weight loss and death. Johne’s disease is spread through the fecal-oral route and is more likely to occur in confined animals. A typical transmission scenario is when a newborn calf is born in a manure-contaminated area and ingests a large dose of the disease-causing organism immediately after birth.

Signs of illness take years to develop, but infected animals can discharge the bacterium and contaminate the environment for other cattle long before signs of illness are observed. Persistent weight loss despite a good appetite is the first sign usually noted. Profuse diarrhea eventually develops and can follow a stressor such as calving or transportation. There is no treatment for this disease. Positive herds can transition to negative status through intensive management practices over many years. Much more information about this disease is available at www.johnes.org.

Acidosis

Cattle wellbeing depends on the health of rumen microbes. The specific types of microbes in a rumen are influenced by diet, especially high-fiber versus high-carbohydrate diets. The sudden or chronic ingestion of excessive carbohydrate loads (e.g., grain) can cause acute or subacute acidosis, respectively. In animals not acclimated to high carbohydrate intake, a sudden increase in dietary carbohydrates will cause a drastic drop in rumen pH and death of essential rumen microbes. Rumen acidosis can cause profuse diarrhea, ulcers, founder, bloat, and even death. Any changes to ruminant rations must be done gradually over a period of a week or more to allow rumen microbe populations to adjust to the new diet and prevent rumen acidosis.

Bloat

Bloat (rumen distension) can be either free-gas or frothy bloat. Free-gas bloat usually develops when normal gasses from rumen fermentation cannot be eructated by the cattle due to an obstruction in the esophagus. This can occur when cattle gulp grain or during the consumption of whole carrots, apples, potatoes, or onions.

Frothy bloat is usually caused by either high-grain diets or ingesting fresh legumes such as alfalfa, clovers, and vetches. Mineral blocks with a frothy bloat preventative (“bloat blocks”) can be used when cattle are grazing on pastures with the potential to cause bloat until the cattle have acclimated to the new forage.

Both types of bloat appear the same (severe abdominal distention on the left side and possibly on the right side as well) and can cause death by suffocation. Consult a veterinarian immediately when bloat is observed because treatment and prevention depend on the type of bloat.

Calfhood diarrhea

In addition to white muscle disease and respiratory diseases mentioned above, diarrhea (“scours”) can be a major problem in young calves. Most causes are contagious. Outbreaks can be magnified by poor sanitation, overcrowding, inadequate cow nutritional status, cold or wet environmental conditions, and insufficient colostrum quality or quantity. Causes can be viral, bacterial, or parasitic. Vaccinations against some of these pathogens can be given to pregnant cattle to boost the level of specific protective antibodies in colostrum. Calves will be passively protected until about 3 months of age if they ingest adequate colostrum within 4 hours of birth. Work with a veterinarian to develop the most effective disease prevention program for specific herds.

External parasites

External parasites include horn flies, face flies, stable flies, heel flies, ticks, and lice. The largest health problem comes from the additional stress these insects cause to animals. When infested, cattle spend more time in the shade and don’t graze, which causes poor performance. Additionally, pink eye could be a major concern.

You can reduce these problems by using fly-repellent ear tags or other parasite control treatments such as dust bags or pour-on agents. Eliminating the areas where pests reproduce also helps reduce the impact of external parasites. Cleaning up old hay feeding areas or manure piles reduces the breeding habitat for many pests.

Internal parasites

Internal parasites such as coccidia, roundworms, lungworms, and liver flukes commonly occur in cattle. These hidden parasites cause poor performance and can kill young animals (particularly coccidia).

Cattle are likely to pick up internal parasites when they are allowed to overgraze (graze pasture plants below 3 inches). Internal parasites also can be a problem in confined areas.

Invasion of the stomach or intestinal wall by a parasite leads to poor digestion of nutrients and damage to organs. Signs of parasite infestation can include scouring (can be bloody with coccidiosis), rough hair coat, weight loss, poor gains, anemia, potbelly appearance, and even death. Use dewormers at strategic times during the year to reduce the numbers of internal parasites in clinically affected animals. Fecal egg counts can help determine parasite loads in individual animals and assess dewormer effectiveness after treatment. Use the correct dose for an animal’s weight.

Cattle develop some degree of immunity to internal parasites as they age. There is also a hereditary component to parasite resistance, meaning managers can select for animals with higher natural resistance to parasites.

There is no need to deworm healthy animals with good body condition that are performing well. Treating only individual animals that are clinically parasitized will save money and slow the development of parasites resistant to dewormers.

Biosecurity

Biosecurity refers to management practices that can reduce the chances of infectious diseases being transmitted onto a farm or ranch or into an animal population. It also refers to practices to reduce the spread of disease if a disease challenge does enter an animal production premise. This includes parasites as well. People and equipment that have been in contact with sick animals should not be allowed onto your farm or ranch.

A biosecurity program is an important part of any beef cattle enterprise, especially when introducing purchased animals to the operation. Quarantine facilities, vaccinations, health monitoring, sanitation, and transportation considerations are all parts of a biosecurity program. Your veterinarian and Extension professional can help you develop a biosecurity plan for your operation.

Marketing your product

There are many different methods of marketing beef cattle. The marketing method appropriate for your operation will depend upon the class and type of cattle. For example, feeder and fed cattle can be sold by direct sales or at an auction; purebred cattle usually are sold at special breed auctions or private sales.

The following are some examples of ways to market beef cattle.

Direct marketing (country dealers)

Direct selling, or country selling, refers to sales of livestock directly to packers, local dealers, or farmers without the use of agents or brokers. The sale usually takes place on the farm, ranch, feedlot, or some other nonmarket buying station or collection yard.

This method does not involve a recognized market. Sellers who direct-market should be aware of possible local and state regulations regarding the private sale of breeding animals or beef for consumption.

Niche marketing

There is increasing interest in marketing through niche outlets. This is especially true for grass-finished operations. The markets might consist of restaurants, stores, individual consumers, or farmers markets for whole or quarters of beef, certain cuts of beef, or specialty beef products. If livestock producers in Oregon wish to sell individual cuts of beef, the animal must be processed at a USDA-inspected facility. If this interests you, research the meat handling requirements, inspections, and permits that may be necessary. This type of marketing usually takes time to develop and may also require a consistent seasonal or yearly supply.

Auction marketing

Livestock auctions or sale barns are trading centers where animals are sold by public bidding to the buyer who offers the highest price per hundredweight or per head. Auctions may be owned by individuals, partnerships, corporations, or cooperative associations. Video or tele-auctions are other forms of auction markets.

Grid marketing

A common practice for large cattle operations is to sell animals directly to a processor, with the cattle priced on a carcass basis. This is commonly known as grid pricing. The cattle owner or feedlot gets paid for pounds of beef, and prices are adjusted for quality grade, yield grade, and carcass weight.

This is usually not a viable option for small beef operations unless the cattle are pooled with other beef cattle and sent to a feedlot.

A steak is not always the same

Consumers, whether purchasing beef in a retail outlet or as part of a meal in a restaurant, use quality as a factor when choosing a cut of beef. Common terms such as “choice sirloin steak” or “prime ribeye steak” denote not only the location of the cut on the animal from which it came but also the USDA quality grade assigned to it. The terms and the grading system are often misunderstood and a source of confusion for both consumers and producers.

Beef grading began in the early 1900s as a way to bring some uniformity to the reporting of what was then called “the dressed beef trade.” Revisions were made to the early guidelines, and in 1927, voluntary beef grading and stamping was put into service. Since 1927, numerous revisions have been made to grading standards to reflect changes in beef production and the processing industry. The goal is still to apply uniformity to particular types of beef regardless of where it is sold.

As previously stated, selling directly to a processor on a carcass basis is not always a viable option for a small beef producer. That said, it is important that producers of every size operation have a basic understanding of how beef is sold and reported in major United States marketing channels. All aspects of production, such as management, health, and feeding, influence the quality and acceptability of the final product regardless of whether or not the beef is actually graded by a federal grader.

There are two categories of grades for beef: yield grade and quality grade.

Yield grade

Yield grade, or cutability, designates the yield of trimmed retail cuts from the carcass. Factors determining yield grade are:

- Fat thickness over ribeye

- Ribeye area

- Kidney, pelvic, and heart fat (KPH), calculated as a percentage of carcass weight

- Hot carcass weight

Yield grades range from 1 to 5, with 1 being the leanest and 5 the fattest (requires the most trimming).

Quality grade

Quality grades designate various characteristics of meat and give the buyer a guide for tenderness, juiciness, and flavor. Grades separate beef into groups that are somewhat uniform in quality and composition.

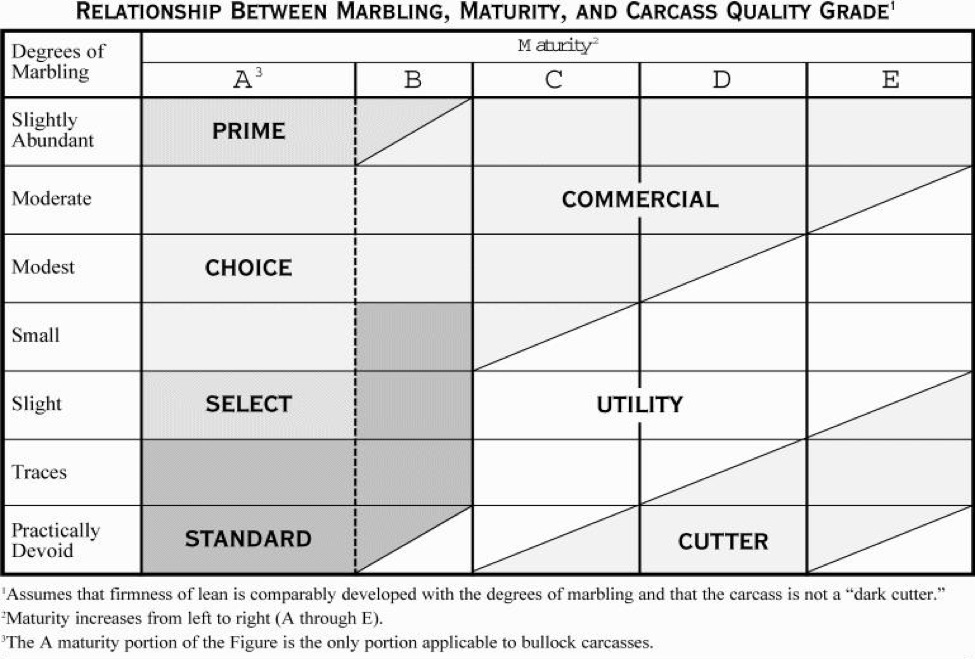

The quality grade of a beef carcass is determined by physiological maturity and marbling. The age of the animal affects the tenderness and texture of the meat. There are eight quality grades used by the U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA).

Figure 1 shows seven of the USDA quality grades and the relationship between marbling and maturity. “Canner,” the lowest grade, is not included. Approximate ages that correspond to each maturity classification are:

A – 9 to 30 months

B – 30 to 40 months

C – 42 to 72 months

D – 72 to 96 months

E – more than 96 months

Beef quality assurance

When consumers go to the store to purchase beef, they want quality meat, free of bruises, dark spots, abscesses, or lesions. Quality assurance means that beef producers monitor the factors that contribute to quality meat, produce a beef product that is free from defects, and ensure that consumers get the quality they want. Quality assurance is not a grade of beef, but rather a voluntary certification that the animal was raised humanely and was of good quality at the time it was delivered to the processing plant.

When you raise beef cattle to sell to a feedlot, processor, or directly to a consumer, you are delivering a food product. The handling, management, and environment on your farm or ranch affect the quality of the product and what the consumer ultimately buys in the store.

Poorly designed facilities and equipment can increase the number of cuts, puncture wounds, and bruises on beef animals. Corrals or chutes with sharp corners or protruding nails or bolts should be altered or repaired.

You must keep records to document that vaccines and antibiotics were administered properly. Abide by all medication label instructions including dosages and pay attention to withdrawal times. Use only vaccines and medications approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration and the U.S. Department of Agriculture.

Beef quality assurance certification workshops to certify producers are conducted by state Extension professionals.

Am I making any money?

Standard ranch or farm records cover all production and financial management aspects of a beef operation. Use records to evaluate your business in terms of efficient use of resources and productivity. Records are important for ranch planning, tax reporting, and applying for credit.

Budgets

Decisions are only as good as the information on which they are based. Budgets provide the information for making ranch or farm management decisions and are designed to estimate the outcomes of future activities.

Budgeting allows you to anticipate problems that you may encounter and to alleviate or avoid them.

Financial records

The ways ranchers keep financial records vary, but the key is to use a system that provides the information you need to meet your responsibilities. The minimum set of financial records should include a balance sheet, a statement of cash flow, and an income statement.

There are several ways to keep accurate records. Until the advent of the computer, all records were kept by hand, and this still is a good method for many farms. Hand-kept records are inexpensive and easy to store.

On the other hand, this method may be slow and subject to errors. Retrieving information can be time consuming with more extensive records. Computerized record systems are available, from simple checkbook balancing systems to sophisticated, double-entry accrual programs. Computerized systems for production records also are available with a range of features and reporting capabilities. Advantages include easy retrieval of information and reduced chance of mathematical errors. However, entering information takes time and must be done properly.

If you choose a computer system, it should meet the requirements and objectives of your individual operation.

Summary

This publication gives an overview of the basics for developing and managing a small beef herd. The Extension Service, veterinarians, and experienced beef producers can be resources to help you develop your enterprise. Careful planning, quality cattle in good health, a marketing plan, and good management should put you on the road to success.

For further reading

From the Oregon State University Extension Catalog:

Cattle Vaccine Handling and Management Guidelines (PNW 637)

Mineral Supplementation of Beef Cattle in the Pacific Northwest (PNW 670)

Selenium Supplementation Strategies for Livestock in Oregon (EM 9094)

Understanding Your Forage Test Results (EM 8801)

Cow talk

A glossary of terms commonly used by people who work with cattle

artificial insemination—introduction of semen into the female reproductive tract by a method other than natural servicing by a bull

antibiotics—medications used to treat bacterial infections

as fed—describes the natural state of a feedstuff including its normal amount of moisture, which contributes to the weight of feed being offered

as fed basis—taking the water-weight of feed into account when feeding animals. Rations are often calculated on a dry matter basis, but the water-weight of feeds must be considered when actually feeding animals. As fed amounts will be 10 to 90 percent greater than dry matter calculations.

backfat—fat thickness measured at the 12th rib

backgrounding—see feeder cattle

balance—the harmonious relationship of all body parts, blended for symmetry and pleasing appearance; for example, a steer that is poorly developed in the hindquarter lacks balance

Bang’s disease—see brucellosis

beef quality assurance—a national program that raises consumer confidence by offering proper management techniques and a commitment to quality within every segment of the beef industry

body condition score—a number from 1 to 5 (or 1 to 9) that reflects the amount of a beef animal’s muscling and fat cover, with 1 being emaciated and 5 (or 9) being obese

bred—mated or pregnant female

breed—animals of like characteristics, such as color and type, similar to those of its parents and past generations

breed character—features or characteristics that distinguish one breed from another; an animal is said to possess breed character when it has many of the characteristics particular to one breed

breeder—the owner of the dam of a calf at the time she was mated

breeding—the act of mating a heifer or cow with a bull; or, artificial insemination

breeding soundness evaluation—annual evaluation conducted on males to ensure adequate health and semen quality to breed desired number of females

brisket—lower chest area in front of the front legs

brucellosis (Bang’s disease)—contagious abortion caused by the bacteria Brucella abortus or B. suis; transmissible to humans

bull—an uncastrated male of any age

buller—a cow in continuous heat due to cystic ovaries or other physical defects

bulling—behavior of a cow in heat; apparent when a cow tries to ride other cows or stands while others try to ride her

calf—a young animal of either sex, under 1 year of age

calving—the time when a cow gives birth to a calf

carcass—the animal after slaughter, with head, hide, internal organs, and legs below the knee or hocks removed

castrate—to remove the testes

characteristic—a physical or behavioral trait in an animal

chuck—the major wholesale cut in the forequarter of a beef carcass

close breeding—line breeding; mating of related animals

closed range—areas of the western U.S. where if livestock escape from fenced areas, their owner is responsible for damage done to property

cod—the scrotum of a castrated male; fills with fat as the animal finishes

colostrum—the first milk from a female after calving, which contains antibodies that prevent disease by providing passive immunity to calves

commercial breeding—breeding of animals primarily to produce market beef

conceive—to become pregnant

concentrates—feeds low in fiber and high in energy or protein; for example, grain is a concentrate

conception—the union of ovum and sperm; the beginning of a new individual

condition—the degree of fatness in animals

conformation—the general structure and shape of an animal

corn silage—whole green corn plants that have been chopped and fermented in an airtight silo, bunker, or bag

cow hocked—hind legs bowed in at the hocks as viewed from the rear

cows—female cattle that have had one or more calves

creep feeding—providing a calf with feed as a supplement to its mother’s milk and pasture

crop—the depression behind the shoulder of a cow; or, an ear mark

crossbred—an animal that results from mating two or more different breeds

cryptorchid—a male bovine with one or both testes undescended

cull—to eliminate an animal from a herd

cutability—carcass cutout value, or yield of salable meat; sometimes called “yield grade” by USDA meat graders

dam—the mother of a calf

dehorning—the act of removing horns from cattle

dewlap—a hanging fold of skin under the neck or above the brisket

diet—type of food(s) an animal is fed; for example, a hay and rolled barley diet, a corn silage diet, or a grass pasture diet (does not indicate amounts)

digestion—the process of breaking down feeds into nutrients in the stomach and intestinal tract; used by the animal’s body for growth and reproduction

disbudding—removing horn nubs on very small calves before horns develop, usually with a hot iron or caustic paste

docile—able to be quiet and gentle, especially under strange conditions

double muscling—a misnomer for an undesirable, genetically controlled enlargement of all muscles of an animal’s body (gross muscular hyperplasia), causing the appearance of bulging muscles

dropped—born; gave birth to

dry matter—what remains after all the water is removed from a feed

dry matter basis—feeding animals using feed values that exclude water content; allows for feeds that differ in water content to be compared accurately. Most rations are formulated on a dry matter basis.

dwarf—an abnormally small, short-legged, early-maturing calf with a mature weight of about 700 pounds; dwarfs usually do not reproduce

embryo—developing young in the uterus during early pregnancy

embryo transplantion—the process of removing one or more embryos from the reproductive tract of a donor female and transferring them to the reproductive tract of recipient females

expected progeny difference (EPD)—EPD values predict the performance of the offspring from an individual animal and are calculated using data from the animal, its ancestry and offspring, and the breed base

estrous cycle—length of time from one heat period to the next; in cattle, 21 days

estrus—the period when a cow will accept a bull for breeding; heat period. Estrus occurs about every 21 days and lasts 12 to 18 hours. It does not occur when an animal is pregnant.

fabrication—cutting a carcass into subprimal and retail cuts of meat

family—tracing ancestry; line of breed

fed cattle—steers or heifers fattened and ready for slaughter

feed efficiency—the number of pounds of feed required for an animal to gain 1 pound of weight; for example, 6.5 pounds of feed per pound of gain

feeder cattle—cattle being grown or raised in preparation for the feedlot. Cattle in this stage of growth also are called “stocker” or “backgrounded” cattle. Feeder cattle include both calves and yearlings.

feedlot—a group of pens, or barn lot, where steers and heifers are fattened for slaughter

fermentation—digestion of feedstuffs via bacteria, protozoa, and yeasts in the digestive tract which releases nutrients the animal uses

fertility test—analysis of semen for live sperm count; tests a bull’s potential ability to produce offspring

fetus—a developing young calf (or any vertebrate) during late pregnancy, after it attains the basic structure of its kind

fiber—structural carbohydrates in plants with varying degrees of digestibility by intestinal microorganisms

finish—the degree of fatness on an animal

fitted—fed, trained, and groomed for show or sale

forage—generally pasture and/or hay or silage

free choice—allowing animals to eat as much as they want at any time

freemartin—female calf born as a twin with a bull calf and infertile

freeze branding—a way of marking cattle for identification. The procedure is to clip hair from the brand area, wet the skin with alcohol, then apply a branding iron cooled in liquid nitrogen or dry ice and alcohol. It works best with dark-skin or dark-hair cattle.

gate cut—a method of impartially dividing a group of cattle by driving them through a gate

gestation—the period between conception and birth of the young; approximately 283 days for cattle

get—calves sired by the same bull

grade—a beef animal with one or both parents not registered or recorded

grooming—care of an animal’s coat; for example, washing, clipping, brushing, etc.

growth promotants—non-nutritive products (implants or feed additives) that improve rate of gain or efficiency of gain

heifer—a female that has not borne an offspring; or, a female that has borne her first calf (“first-calf heifer”)

herd sire—the principal breeding bull in a herd

heredity—the characteristics an animal receives from both parents, determined by genes present in the sperm and egg that unite to create a new individual

heritability—the part of an animal’s variation from other animals caused by heredity and not by the environment

hindquarters—the back half of a beef carcass, usually divided between the 12th and 13th ribs

hooks—highest and forwardmost protuberance of the pelvis on each side of the hindquarters

immunoglobulins—proteins contained in blood and colostrum and on some body surfaces that help defend against specific disease-causing organisms; antibodies

inbreeding—when sire and dam are close relatives; see close breeding

KPH—kidney, pelvic, and heart fat; the internal fat of the carcass, calculated as percent KPH

lactation—the period during which a cow produces milk after calving

line breeding—selective breeding; sire and dam are of the same heredity, but not as closely related as with inbreeding

management—selection, feeding, and care of animals

marbling—fat within the muscle or lean part of a beef carcass as viewed in a cross section of the muscle

market beef—a steer or heifer fed for producing meat

market value—the price received for live animals

meat packer, processor—one who harvests live animals, fabricates the carcass, and sells the meat to retailers, restaurants, and purchasers

nursing—a calf getting milk from its mother; also, a cow producing milk for her calf

nutrient—ingredient in food that helps develop bones, muscles, and fat; includes protein, carbohydrates, minerals, vitamins, and water

open—a nonpregnant female

open range—legally designated areas in the West where vehicle operators must be aware of roaming livestock and are financially responsible for any losses that may occur

outcrossing—mating of unrelated animals within the same breed that have no common ancestors in the first generation

ovum (plural, ova)—a female sex cell produced in the ovary; contains the half of the genes carried by the female

ovulation—release of ova into the oviducts; occurs 12 to 15 hours after the end of estrus in cattle

parturition—birth

pasture bred—a cow serviced by a bull in the pasture

pathogen—disease-causing agent such as a bacterium, virus, or fungus

pedigree—a genealogical tree of an individual’s ancestry

performance test—a measure of performance; specifically, rate and efficiency of growth and carcass traits

pin bone—the bony portion of the pelvis that protrudes on each side of the tailhead

placenta—the afterbirth

polled—naturally or genetically hornless

pregnant—a heifer or cow that has conceived and not yet calved

production records—measure of a cow’s productivity based on number and weaning weights of calves she produced in her lifetime

progeny test—the measure of an animal’s (usually a bull’s) offspring; generally given to determine transmission of heritable traits such as rate of gain, conformation, muscling, dwarfism, etc.

protein supplement—a food substance containing high concentrations of protein; for example, cottonseed meal, canola meal, or soybean meal

purebred—registered or unregistered (grade) member of a certain breed whose ancestors were also of the same breed

quality grade—the USDA rating (Prime, Choice, Select, Standard, Commercial, Cutter, Utility, and Canner) given to a beef carcass based on marbling, age of the animal, and color of the lean meat

ration—the amount of specific feed ingredients given to an animal during a 24-hour period

registered—meets the requirements of a recognized breed association and is recorded in its herd book

retail cuts—the cuts of beef bought by consumers in grocery stores or meat markets

retailer—a market that sells beef to customers

ribeye—the main muscle exposed when a carcass is separated into front and hind- quarters; the area of the ribeye, calculated at the 12th rib, is used as an indication of the animal’s muscling

roughages—feeds such as hay, silage, and pasture, that are high in fiber and low in digestible nutrients

ruminant—animal such as cattle that chews its cud and has a stomach composed of four parts: the rumen, reticulum, omasum, and abomasum. Ruminants rely on gastrointestinal microbes to digest fibrous diets.

safe-in-calf—pregnant beyond doubt; usually reported after a veterinarian’s examination

scale—refers to an animal’s development in size and frame in terms of height, length, and width, rather than weight

scours—diarrhea; young calves may get scours by consuming too much milk or by pathogen infection

scrotum—the bag enclosing the testes

scurs—small, imperfectly formed horns; may regrow from improper disbudding or dehorning

seedstock—foundation animals for establishing a herd

served—a bred female, not guaranteed safe-in-calf

service—breeding

settle—to become pregnant

sheath—the tubular fold of skin into which the penis is retracted

sickle hocked—an undesirable condition in which the hind legs curve under the body in a sickle fashion, as viewed from the side

sire—the father of a calf

spay—to remove surgically the ovaries of a female animal so it cannot get pregnant

springer—a heifer or cow showing signs of advanced pregnancy; near to calving

stag—a male bovine castrated after sex characteristics are developed; also called an ox

steer—a male bovine castrated before sexual maturity

stocker—see feeder cattle

structural soundness—the physical condition of the skeletal structure, especially feet and legs

switch—the tip of the tail where the hair is longest

synchronization—manipulating the estrous cycle of beef females so they can be bred at approximately the same time

tattoo—an indelible mark or figure used on registered animals for permanent identification, usually in the ear

trait—a distinguishing quality or feature

trimness—freedom from excess fat and flabbiness in the brisket, underline, and flanks

type—the sum total of all the characteristics that make up the ideal beef animal or that suit any animal for a specific purpose; for example, beef type or dairy type

vaccine—a substance used to stimulate the production of antibodies and provide immunity against one or several bacterial or viral diseases

weaned—no longer nursing the dam; weaning is the act of separating a calf from its mother

weanling—a calf recently weaned

weight per day of age—a measure of weight gain; usually from birth to weaning, or from birth to 1 year old

withdrawal period—wait-time required for medication in a treated animal’s body to clear to acceptable levels before any food products from the animal are fit for human consumption; also called withholding time

yearling—an animal about 1 year old or older

yield grade—numerical rating of a beef carcass based on estimated percentage of carcass weight in boneless, closely trimmed retail cuts from the round, loin, rib, and chuck; yield grades range from 1 to 5, with 1 being the leanest and 5 being the fattest

Gene J. Pirelli, regional Extension livestock and forage specialist, and Dale W. Weber, professor emeritus, Department of Animal and Rangeland Sciences, both of Oregon State University; and Susan Kerr, NW regional livestock and dairy Extension specialist, Washington State University

Acknowledgments

We wish to thank the following reviewers for their helpful comments: KC Olson, PhD., W. M. & F. A. Lewis Distinguished Professor, Animal Sciences and Industry, Kansas State University; Gary Fredricks, County Director, Cowlitz County, Washington State University Extension; and Nick Gehling, Illinois beef cattle producer.

© 2018 Oregon State University

Extension work is a cooperative program of Oregon State University, the U.S. Department of Agriculture, and Oregon counties. Oregon State University Extension Service offers educational programs, activities, and materials without discrimination on the basis of race, color, national origin, religion, sex, gender identity (including gender expression), sexual orientation, disability, age, marital status, familial/parental status, income derived from a public assistance program, political beliefs, genetic information, veteran’s status, reprisal or retaliation for prior civil rights activity. (Not all prohibited bases apply to all programs.) Oregon State University Extension Service is an AA/EOE/Veterans/Disabled.