Management planning—the words conjure up visions of corporate boardrooms and gray suits. As a woodland owner, your management planning does not need to be an intimidating process. Simply put, a forest management plan describes your property, what you want to do with it, and how and when to carry out your plans for it. This publication describes both why and how to develop a forest management plan.

Good plans will change with time. Whether you are just starting out as a woodland owner or are a longtime, active forest manager, it is never too soon or too late to develop a plan. A management plan is beneficial to a wide range of owners, whether you are an active timber manager or you own woodland primarily for personal enjoyment. As you learn more about forestry and your own objectives, you can change your management plan to fit expanding knowledge and new situations.

Why plan?

There are many reasons why it is helpful to have a management plan for your property. Primarily, a plan helps you:

1. Consider what you might do on your property to improve its condition.

2. Save time and money, and avoid costly mistakes that may not be correctable.

3. Organize your business records and keep track of activities on your property.

4. Communicate with others who use the property or who may be caring for it in the future.

5. Demonstrate to others your commitment and interest in continued woodlot management.

Let’s look at each of these reasons in more detail.

Consider what you might do on your property to improve its condition.

Planning requires careful thinking about why you own your property, what you would like to see happen to it, what it might produce, and how much time and money it will require. Thinking and learning about possible management options will go a long way toward helping you establish your objectives.

When you set goals, consider your constraints or limitations. Personal and economic constraints might include limited time, money, and equipment. Biological and physical constraints might include poor drainage, steep ground, rocky soils, or disease and insect problems. These limitations may narrow your options and require that you set goals and objectives that are more attainable.

An integral part of setting attainable goals involves making a careful inventory of the resources on your property. A timber inventory—with a level of detail appropriate to the scale of your property and your objectives—is one important aspect of this process, but not the only one. Through forest management planning you take stock of all the resources on your property, such as roads and infrastructure, water sources, wildlife habitat, recreational assets, nontimber forest products, and anything else that is relevant to your family and your goals.

Save time and money, and avoid costly mistakes that may not be correctable.

Your management plan will help you prioritize activities, time, and capital, and keep focused on the big picture so that you can realize your long-term goals.

By developing a well-organized management plan, you can prepare a logical sequence of activities rather than a hit-or-miss schedule. Plan what needs to be done—and how and when to do it—before you begin. For example, by ordering seedlings at the correct time and completing the site preparation and weed control on schedule, you will save time, labor, and money.

Planning also helps you work with forest advisers. A good plan clearly shows the extent of your resources and allows forest advisers to more easily outline options and make suggestions based on your needs.

Organize your business records and keep track of activities on your property.

Some landowners use their management plans like a journal, recording very specific activities. Others record only major events, such as a harvest. Keeping notes on all activities, such as reforestation, thinning, harvesting, and equipment purchases, provides a reference for the future.

For example, reforestation records might include notes about site preparation, planting dates, tree species, stock (size, nursery, etc.), herbicides, and animal protection methods. Document your management results as well. Did the seedlings survive? Was the planting stock good quality? Was the herbicide effective? Both successes and failures provide important information.

In addition, list all financial details, such as costs, incomes, receipts, and bills of sale. Thorough and accurate financial records are necessary to complete tax forms, especially if you are operating your tree farm as a business. Your accountant can help you organize your financial records.

Communicate with others who use the property or who may be caring for it in the future.

As the primary manager of the property, other family members may look to you as the “forester in charge.” By sharing a plan that outlines your activities and your reasons behind them, others can learn about the forest and may develop a shared interest in being involved in its management.

Many woodland owners have children or others who stand to inherit the property but who are not currently involved in its day-to-day management. A management plan provides a written history of your property that can help future managers understand what your vision is, what you’ve learned about the property, what you’ve accomplished, and who to go to for help when you are not around for them to ask. If you plan to transfer your property to heirs, then succession planning and estate planning may also go hand in hand with your management plan.

Demonstrate to others your commitment and interest in continued woodlot management.

Forest certification systems, such as the American Tree Farm System and Forest Stewardship Council, require a written forest management plan that demonstrates sound stewardship principles. Financial assistance to implement practices to improve the ecological function of your property sometimes depends on having a management plan. Lending agencies, planning commissions, county assessors, or land trusts may require some proof of your commitment to long-term forest management. Management plans can be one form of evidence of this commitment.

How to write a plan

Writing a management plan takes time and effort. It not only requires defining your vision and purpose for management, but also requires knowing your property, its physical characteristics, and its biological potential. Many landowners feel that there is just as much value to be gained from the process of writing their own plan as there is in the product itself. Through the process of writing a plan, you learn about your property, think carefully about its possibilities, and become invested in the management recommendations that you include.

Fortunately, there are many resources available to help you collect the information you need and organize it into a management plan. The Oregon Forest Management Planning Website is an online reference guide for writing plans (see “Additional Resources”). Other useful resources for developing management plans include publications about woodland management, cruising and inventory guides (see “Additional Resources”), and forestry educational programs sponsored by Extension or other organizations.

Another option is to have a plan prepared for you by a forestry consultant. The cost of having a consultant write a plan can range from about $1,000 for a small property to several thousand dollars for a larger, more actively managed property or a property with multiple timber types. Funding may be available from state (Oregon Department of Forestry) and federal (Natural Resources Conservation Service) agencies to offset the cost of hiring a consultant to prepare a plan for you.

General elements to include in your management plan are:

• Introduction

• Maps and photos

• Goals and objectives

• Resource descriptions

• Management recommendations and schedule

• Recordkeeping

These elements are discussed further below.

Introduction

Introduce your management plan with a brief overview of your property and its location. Include some history of its management under your ownership and what you know about past owners and their use of the land.

Maps and photos

As a landowner, you need to know the exact location of your property. Consult legal descriptions and deeds. Obtain property survey maps showing your boundaries and corners. Locate these points in the field to avoid possible boundary disputes.

An aerial photograph is a helpful tool for providing a visual overview of the property and its context with respect to surrounding land uses. Aerial photos enable you to recognize and map vegetative cover (brush, trees, pasture, etc.) and may help locate property boundaries. They also help you map existing road systems and plan new ones.

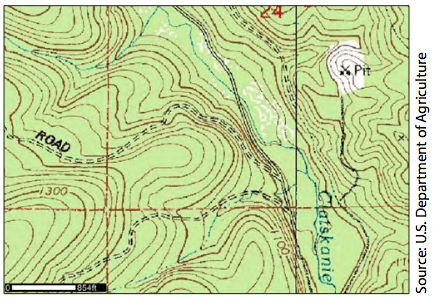

Other useful maps include topographic maps (also called “topo” or contour maps) and soil maps. Topo maps help orient you to the property and the lay of the surrounding land. They are especially useful when used with aerial photos to interpret and check land features. Common features shown on topo maps are drainages, relief or contour lines, and constructed improvements, such as roads and buildings (Figure 1).

Knowing the soils on your property is very important when developing a management plan. Details on soil properties that influence tree growth, such as soil depth, texture, and productivity, can be found in soil survey reports. Soil reports may also contain information that affects engineering activity (e.g., logging and road building) and data for other uses.

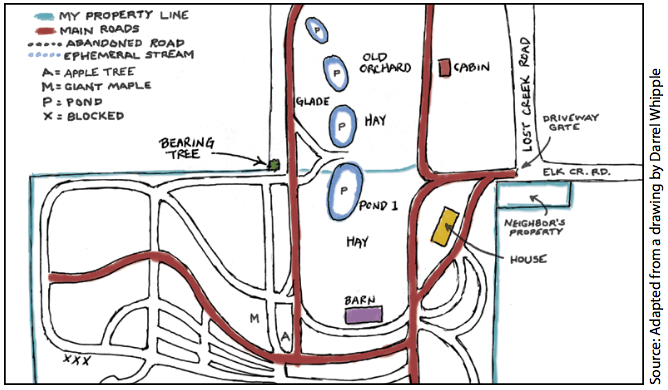

It is useful to have a base map that shows features such as streams, roads, gates, and structures. There are several options for creating a base map, including hand-drawn maps (Figure 2), computer-generated maps, transparent overlays that can be superimposed on a photograph, and aerial photos that have been digitally marked up.

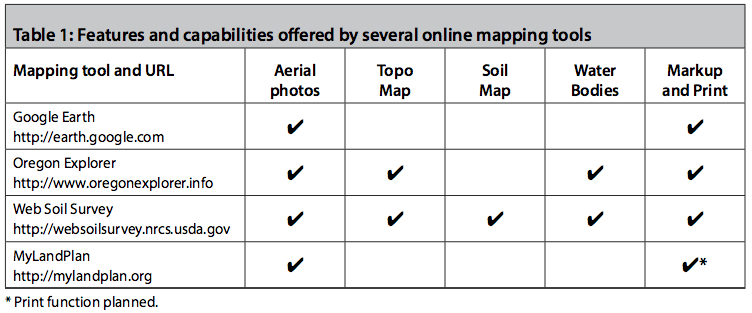

Online mapping tools have made aerial photos and maps easy to obtain and mark up digitally. Google Earth, Oregon Explorer, Web Soil Survey,and MyLandPlan are a few useful mapping sites. Table 1 provides links to these sites and details on their capabilities. If you do not have easy computer access, the local office of one or more of these government agencies can help you obtain the maps and photos you need:

• U.S. Department of Agriculture— Natural Resources Conservation Service (NRCS)

• Oregon Department of Forestry

• Your local Soil and Water Conservation District

• Your county assessor

• OSU Extension Service

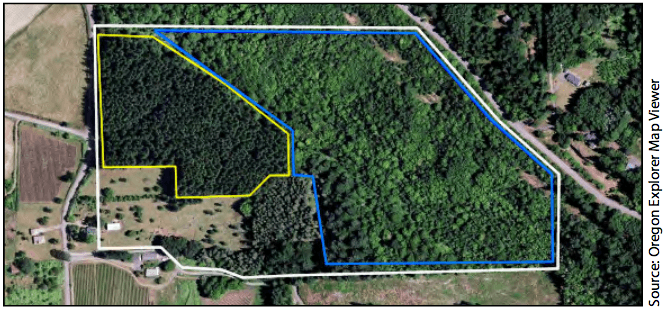

An important component of mapping is recognizing and delineating vegetative types or management units. These are areas on your property that are distinct from one another in terms of tree age, species composition, management history, and/or management objective. Figure 3 shows a property with two management units.

Goals and objectives

Perhaps the most important part of any plan is articulating your goals and objectives. Your goals are your primary uses or reasons for owning the property, as well as your intentions for the future. Common goals include maintaining the property for family enjoyment,producing periodic income from timber sales, and providing for a diversity of wildlife. But there are many other possibilities.

By taking a look at what you expect to do with your land, you can begin to identify the most important resources (trees, soil, water, recreation, development sites, fish, wildlife, etc.), the scope of the resource inventory you will need, and whether what you want from your land is possible and practical.

Objectives are more specific than goals and will vary with the individual landowner and the condition of the property. Examples of some common goals and sample objectives are listed in Table 2.

Resource descriptions

Once you clearly state your goals and objectives, your next step is to assess the current condition of your property through a series of resource descriptions. Some of the information for these resource descriptions will be gathered through a field inventory, which is described in the next section. Common resources to be addressed include:

Forest Vegetation (Timber). Include a description of each stand or management unit, including age, species composition, stocking, and other details.

Soils. Describe the soils on your property. Include in your description: their series name, characteristics, and relation to forest management. Refer to the soil maps and soil reports described previously.

Water. Describe (and indicate on a map): streams and wetlands and their classifications; springs and ponds; and riparian habitat condition.

Wildlife. Identify: species known to inhabit the property; species of particular interest to you; and habitat elements that are missing or present for desired species.

Access. Show the existing road system on your property and adjacent properties; include rocked and dirt roads. Including roads on a map or overlay is helpful.

Forest health. Identify: insect, disease or abiotic concerns; wildfire hazard; invasive weed presence; and strategies employed to address these issues.

Protected resources. Acknowledge any known sensitive, threatened, or endangered species; indicate cultural resources or historical sites that require protection.

Recreation and aesthetics. Describe current or potential recreational or educational uses of the property; include a description of any aesthetically important areas.

Inventory

Through a field inventory, you collect much of the information needed to populate the resource descriptions of your plan. A detailed inventory examines your property’s timber management potential, recreational possibilities, wildlife habitat, and other resources.

Conducting an inventory is time-consuming and hard work, so it is important that you consider what information you need, and how to measure and record it before you start. There are several Extension publications and other resources that describe inventory methods (see “Additional Resources”).

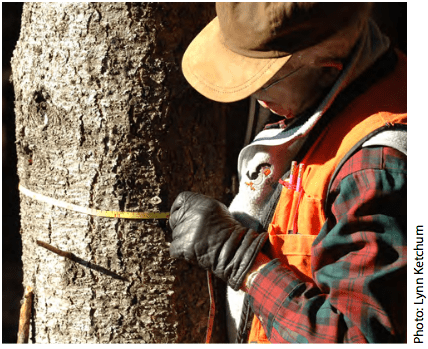

Make your inventory accurate and reliable enough to meet your information needs, and tailor it according to your objectives. For example, if you expect to sell timber from your property in the future, it is useful to know how much timber you have, how fast it is growing, and what its present and future value might be. On young forest stands, you can use a stocking survey to evaluate the condition of the plantation and indicate replanting or animal protection needs. This survey requires only a count of the seedlings present and their condition. For older forest stands, your inventory might require measuring tree diameters and heights plus information about age and growth rate (Figure 4). You may also choose to inventory nontimber forest products, native plants, wildlife use, or other resources, depending on your goals and how you use the property.

Management recommendations and schedule

The essence of any woodland management plan is the recommendation section. Everything discussed thus far leads to the question, “What should I do on my property?”

The answers are not always simple. Often you have several choices. However, having the best possible information about your property will help you establish priorities and decide what to do this year, next year, and the years that follow.

The recommendations part of a management plan can be difficult to write. It requires a background in forestry and experience with the practical aspects of land management. As you interpret the information from your woodland inventory, be sure to seek the advice of other woodland owners and professional foresters. Their help and ideas may spell the difference between success and failure.

There are usually two types of management recommendations: those that deal with what to do with your property and those that deal with when to do it. Recommendations for what to do with your property summarize the activities and operations needed for each management unit or resource. For timber areas, these may include recommendations for pre-commercial or commercial thinning (including necessary tree-spacing guidelines), or harvesting and regeneration (including site preparation, planting, and spacing). Habitat enhancement activities, such as riparian plantings, food plots, or the creation and placement of downed logs or brush piles, might also be included. Road improvements, trail building, and weed control are other activities that may be recommended.

For each recommendation you should describe specifically what is to be done, what special equipment will be needed, and what follow-up practices you must plan.

Recommendations for when to carry out activities on your property include a management activity schedule, which describes your timing, budget, and priority list. You will need to describe work needs for each management unit for the next 2, 5, or 10 years or longer. Estimate the person-days of labor and cost for each job. To be most useful, this account should include estimates of income and expenses for each project.

Some management activities will need to be completed by certain deadlines; others will be more flexible. For example, you might have a planting project that, for best success, needs to happen in the first or second winter after harvest. In that case, you might decide to delay reclaiming a 15- or 20-year-old brushfield because converting it won’t be any different this year, next year, or in 5 years.

Recordkeeping

The importance of good recordkeeping cannot be overstated. Your records will be valuable as you review results of activities, update your tax accounts, and plan new activities. By incorporating recordkeeping into your management plan, the plan becomes a living document, constantly updated to reflect recent activity.

Two types of records that forest owners should maintain relate to forest management and financial issues. Some suggestions for these are shown below. Obviously, they will vary with every property and circumstance.

Forest management records

Reforestation. For each area you plant, describe the site preparation (method, operator, costs, etc.), seedling establishment, and maintenance (planting contractor, costs, species planted, survival, animal protection, etc.).

Thinning. For areas you thin, record previous stand history and condition, stems per acre, tree spacing, operator, costs, and the material you remove.

Harvesting. List logging details, such as the quality, quantity, and value of the products you remove. Also show gross and net receipts and the harvest method, operator costs, contractor, and dates.

Financial records

Depletion. This establishes the initial value of your land and the buildings and equipment on it at the time of purchase. It is essential for calculating taxable income following harvest and depreciation on equipment.

Operating expenses. This documents the current year’s operating expenses, such as trips to the tree farm, costs of materials and supplies, fees for professional services, and other items for income tax purposes. Keep the bills, receipts, and bank statements that document these expenses.

For more information on recordkeeping, see “Additional Resources.”

Summary

A forest management plan is an important tool for defining and communicating your vision for owning and using your property, assessing the current condition of your forest resources, and setting a course of action to keep your forest healthy, productive, and meeting its potential. Numerous online tools and guides have made it easier than ever to collect maps and other information to put into your plan. It is never too late to get started.

Once you finish your plan, remember that it should not be cast in stone. Refer to it often and update it regularly; forest management is a long-term process. It’s difficult enough to predict product values next year, not to mention in 50 or 60 years. Over generations, your family’s purposes for owning your property may evolve. A management plan can help you look at your options, make decisions, and plan for tomorrow.

Additional Resources

There are a number of other helpful publications available on various topics related to forest management planning.

OSU Extension Service publications

Oregon State University Extension Service publications available online at http://extension.oregonstate.edu/catalog/

• Incentive Programs for Resource Management and Conservation (EC 1119)

• Recordkeeping: A How-to-do-it Guide for Small Woodland Owners (EC 1187)

• Best Management Practices for Maintaining Soil Productivity in the Douglas-fir Region (EM 9023)

• Basic Forest Inventory Techniques for Family Forest Owners(PNW 630)

• Measuring Timber Products Harvested from Your Woodland (EC 1127)

• Tools for Measuring Your Forest (EC 1129)

• Measuring Your Trees (EM 9058)

• Management Planning for Woodland Owners: A Visual Guide (EM 9065) See the shaded box for more information.

Other publications and websites

• Inventory and Mapping: A Beginner’s Guide to Basic Inventory and Digital Mapping of Nontimber Forest Products on Small Private Forestlands. By Eric Jones, Rebecca McLain, and Lita Buttolph.

http://www.ntfpinfo.us/docs/ifcae/JonesMcLainButtolph2012-BasicNTFPInve…

• Oregon Forest Management Planning website

http://outreach.oregonstate.edu/programs/forestry/oregon-forest-managem…

Trade-name products and services are mentioned as illustrations only. This does not mean that the Oregon State University Extension Service either endorses these products and services or intends to discriminate against products and services not mentioned.

Use pesticides safely!

- Wear protective clothing and safety devices as recommended on the label. Bathe or shower after each use.

- Read the pesticide label—even if you’ve used the pesticide before. Follow closely the instructions on the label (and any other directions you have).

- Be cautious when you apply pesticides. Know your legal responsibility as a pesticide applicator. You may be liable for injury or damage resulting from pesticide use.

© 2018 Oregon State University.

Extension work is a cooperative program of Oregon State University, the U.S. Department of Agriculture, and Oregon counties. Oregon State University Extension Service offers educational programs, activities, and materials without discrimination on the basis of race, color, national origin, religion, sex, gender identity (including gender expression), sexual orientation, disability, age, marital status, familial/parental status, income derived from a public assistance program, political beliefs, genetic information, veteran’s status, reprisal or retaliation for prior civil rights activity. (Not all prohibited bases apply to all programs.) Oregon State University Extension Service is an AA/EOE/Veterans/Disabled.