History and background

The Japanese beetle (Scarabaeidae: Popillia japonica Newman) is native to Japan, where it is a pest of minor importance. In Japan, a combination of few suitable larval habitats, cooler temperatures and an effective parasite keeps Japanese beetle populations in check. JB adults are generalists that can feed on more than 300 plant species, including field crops, berries, fruit trees, vegetables and a wide array of ornamental plants. JB grubs (the immature stage of JBs) feed on grass root systems.

When JBs were first found in southern New Jersey in 1916, they benefited from a favorable climate and a lack of natural enemies to manage population numbers. As American lawn culture rapidly increased in the 1950s and 1960s, JB numbers increased dramatically on the East Coast. Today, JB is considered the No. 1 most-damaging turfgrass pest in eastern and Midwestern states, where it is established. Simultaneously, this pest has brought large-scale destruction to garden plants and agricultural crops. JBs have also been found in the southeast, in North and South Dakota, Montana, Texas, Colorado and Idaho. Many introduced populations west of the Rocky Mountains have been targeted for eradication.

In summer 2016, 369 JBs were trapped in northwest Portland in Washington County. The high number of catches in northwest Portland suggests that a localized infestation had been present for more than a year, and a breeding population had established. Over two-thirds of the beetles caught came from three traps, out of approximately 150 traps in the immediate vicinity. As of 2021, JB has been found in Washington and Multnomah counties and one small area of Clackamas County.

This is not the first time that the beetle has been found in Oregon. The Oregon Department of Agriculture has conducted early detection surveillance for this pest species for over 35 years. Investments In early detection surveillance have repeatedly helped to keep this beetle from broadly establishing in our state.

Identification

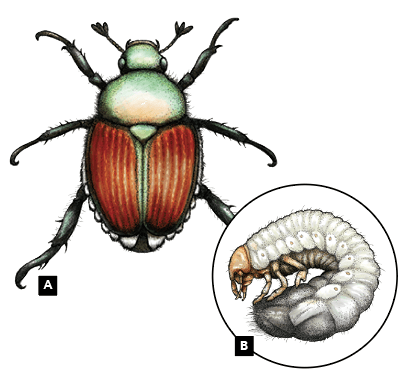

Adult JBs are oval in shape, about ⅜-inch long, and have a dark green, metallic head and tan, metallic elytra (hardened forewings). Key characteristics of adult beetles include two white tufts at the rear and five white tufts of hair along each side of the abdomen (Figure 1A).

JB grubs have the typical “C” shape of scarab beetle larvae. They are also known as white grubs because of their creamy, almost translucent color (Figure 1B).

Life cycle and scouting

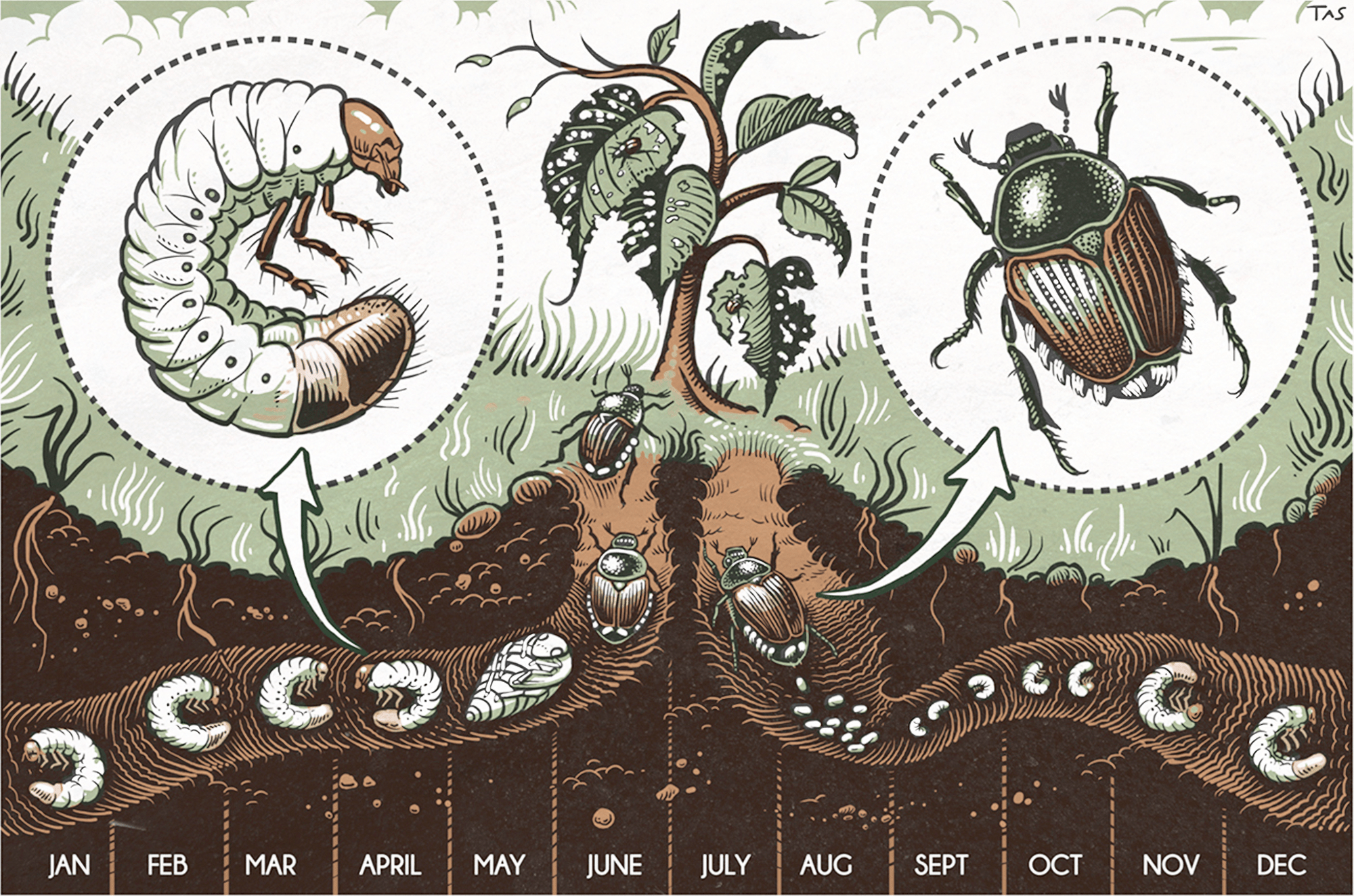

Because the JB is relatively new to Oregon, the exact timing of its life cycle may be slightly different than in eastern states. It typically has one generation per year, with adults emerging in early summer. Females lay 40 to 60 eggs over a two- to three-week timeframe during the summer months.

The beetles overwinter as grubs and are close to the soil surface in the fall and in the spring (Figure 2). Grubs begin feeding when they emerge from the egg.

Active feeding in the soil occurs from late summer until early fall and then to a lesser degree in the spring, when soil temperature increases.

If they become widespread and established in Oregon, gardeners and others should notice the appearance of adult JBs during the summer months. Adult beetles are strong fliers. If you see adults at a site, it does not necessarily mean that there are grubs in the soil. The adults may have flown in from another location and may not choose to lay eggs at that particular site.

Adult females prefer to lay eggs in warm, slightly moist soil with lots of organic matter.

Japanese beetle damage

Japanese beetle damage varies with the life stage of the insect. Adults feed on plant foliage, skeletonizing the leaves by feeding between leaf veins (Figure 3). The beetles also feed on softer plant tissues such as flower petals, which can cause a more generalized, ragged feeding pattern. Grubs live in the soil and feed on grass roots. Pastures, natural grassy areas, golf courses and lawns are particularly vulnerable. Grub feeding can result in severe root pruning that limits the plant’s ability to acquire water and survive in drought stress situations, often resulting in large dead patches of grass (Figure 4).

Reporting suspicious beetles

Early detection and rapid response to eradicate the JB is the best defense to keep it from becoming widely established in Oregon. If you find a JB suspect, bring it to your local OSU Extension office for identification or report it to the Oregon Department of Agriculture, either online or by calling 1-866-INVADER. Keen eyes and a timely report could be vital for keeping this pest from establishing in Oregon.

Control measures

Cultural controls

Commercial traps are available for JB, but their effectiveness is mixed. The trap includes a female sex pheromone that attracts both males and females, thus reducing egg-laying. At this time, JB traps are best used by commercial and government organizations for monitoring purposes rather than as a landscape JB control.

Gardeners and landscape designers can choose plants that are less attractive to the beetles, and avoid or replace plants preferred by the beetles.

Plants resistant to JB feeding include dogwoods, pines and lupines. Ornamental plants that JBs particularly prefer for feeding are Japanese maples, grapes, roses and hibiscus.

Japanese beetle adults can be managed by hand. Gardeners can shake infested plants and plant parts over a jar of soapy water to remove and kill the beetles.

Reduce or eliminate irrigation to lawns when adult females are laying eggs and early instar larvae are developing. That will help lower their survival rate. Allowing lawns to go dormant during the summer months could be a useful management tactic.

Prevention

If you are outside the JB quarantine area, be cautious when sharing plants with friends and neighbors. Check for grubs that could have been moved in the soil when you trade or share plants. If you are in a yard debris quarantine area, do not trade or share plants.

Eradication

The Oregon Department of Agriculture has actively engaged in eradication activities since 2017 due to the serious threat the establishment of JB would bring to Oregon’s urban landscapes and agricultural industries. The threat of the Japanese beetle becoming established in Oregon cannot be overstated. It is more than a nuisance and garden pest. Japanese beetle is a threat to agricultural crops, gardens, public parks and urban forests that are essential to Oregon’s character, economy, landscape and way of life. Due to this threat, the ODA will be treating the areas of Washington, Multnomah and Clackamas counties where the beetles are found.

We do not recommend that individual homeowners use products to control beetles on their property at this time. We encourage those within the treatment area to consent to collaborate with the ODA to ensure proper treatment and eradication efforts against Japanese beetles. The ODA regularly contacts households within the treatment area to inform residents of the need to treat, and to arrange for the application of insecticides that can limit or eradicate this pest. Oregonians within the yard debris quarantine boundary must adhere to the rules and not engage in plant swaps or sales that move plants outside of the quarantined area.

Authorities believe the current population was brought to Oregon by people moving from infested states. The new residents may have brought their outdoor potted plants with them. Those pots likely contained JB grubs in the soil.

For more information

- Japanese beetle informational website, Oregon Department of Agriculture

- How to Reduce Bee Poisoning from Pesticides, PNW 591. Oregon State University Extension Service.

- Integrated Pest Management of Japanese Beetle in North Dakota, E1631. North Dakota State University Extension Service.

- Managing the Japanese Beetle: A Homeowner’s Handbook. United States Department of Agriculture, Animal and Plant Health Inspection Service.

References

- Campbell, J.F., E. Lewis, F. Yoder, R. Gaugler. 1995. Entomopathogenic Nematode (Heterorhabditidae and Steinernematidae) Seasonal Population Dynamics and Impact on Insect Populations in Turfgrass. Biological Control 5:598–606.

- Potter, D.A. and D.W. Held. 2002. Biology and management of the Japanese beetle. Annual Review of Entomology 47:175–205.

- Potter, D.A., A.J. Powell, P.G. Spicer and D.W. Williams. 1996. Cultural practices affect root-feeding white grubs (Coleoptera:Scarabaedae) in turfgrass. J. Econ. Entomol. 89:156–64.

Trade-name products and services are mentioned as illustrations only. This does not mean that the Oregon State University Extension Service either endorses these products and services or intends to discriminate against products and services not mentioned.