What is lead?

Lead is a colorless, odorless and tasteless toxic metal.

How do you know if you have lead in your well water?

The government does not test private well water. It is up to you. Testing your water is the only way to know if lead is present.

How does lead get in your well water?

Lead most likely enters from household plumbing. For this reason, lead is a potential concern for all homes whether on a public or private water supply. Depending on its other chemical characteristics, the water itself dissolves lead from leaded solder or lead pipes in plumbing systems in a process called corrosion. Laws have restricted the amount of lead allowed in new pipes, fixtures and solder, but many homes contain older materials.

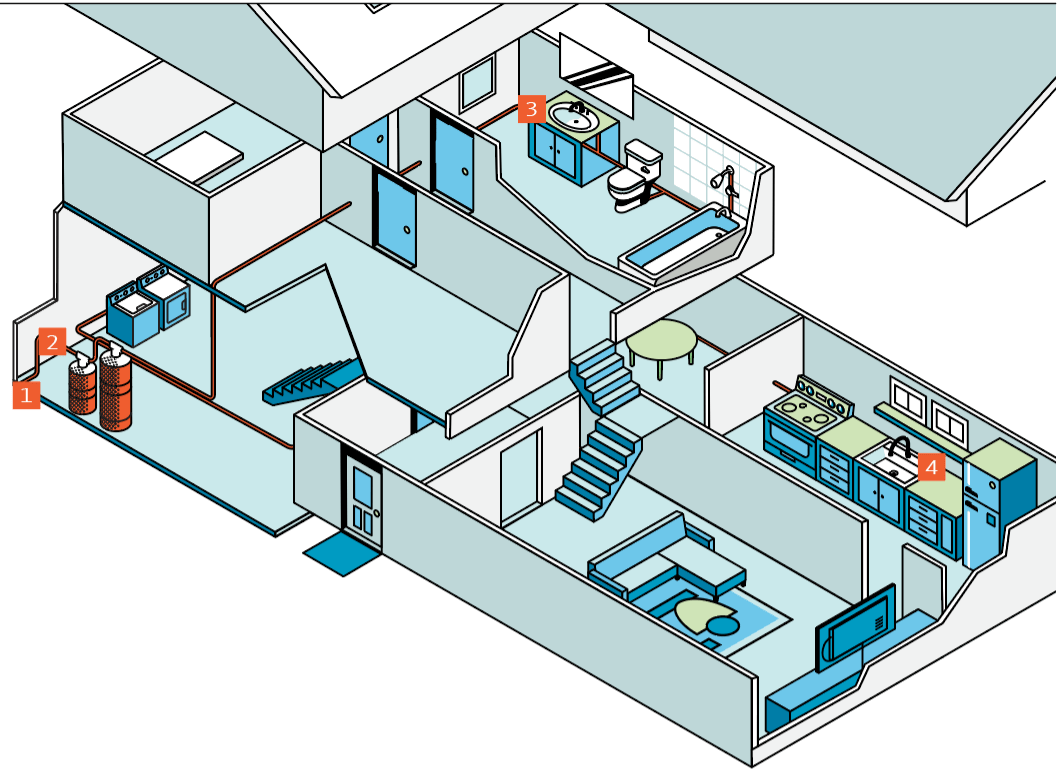

Potential sources of lead

- Lead service line: The service line is the pipe that runs from the water main to the home’s internal plumbing. Lead service lines can be a major source of lead contamination in water.

- Galvanized pipe: Lead particles can attach to the surface of galvanized pipes. Over time the particles can enter your drinking water.

- Faucets: Older fixtures inside your home may contain lead.

- Copper pipe with lead solder: Solder made or installed before 1986 contained high lead levels.

Why should you be concerned about drinking water contaminated with lead?

Lead is a known health hazard. It is toxic even at very low levels. Lead is a serious environmental health hazard for children under 6 in the U.S. and can cause many conditions. Children’s rapidly growing bodies absorb lead more quickly and efficiently than adults. Adults are also at risk. Lead will NOT go away on its own, but you can remove lead with proper water treatment.

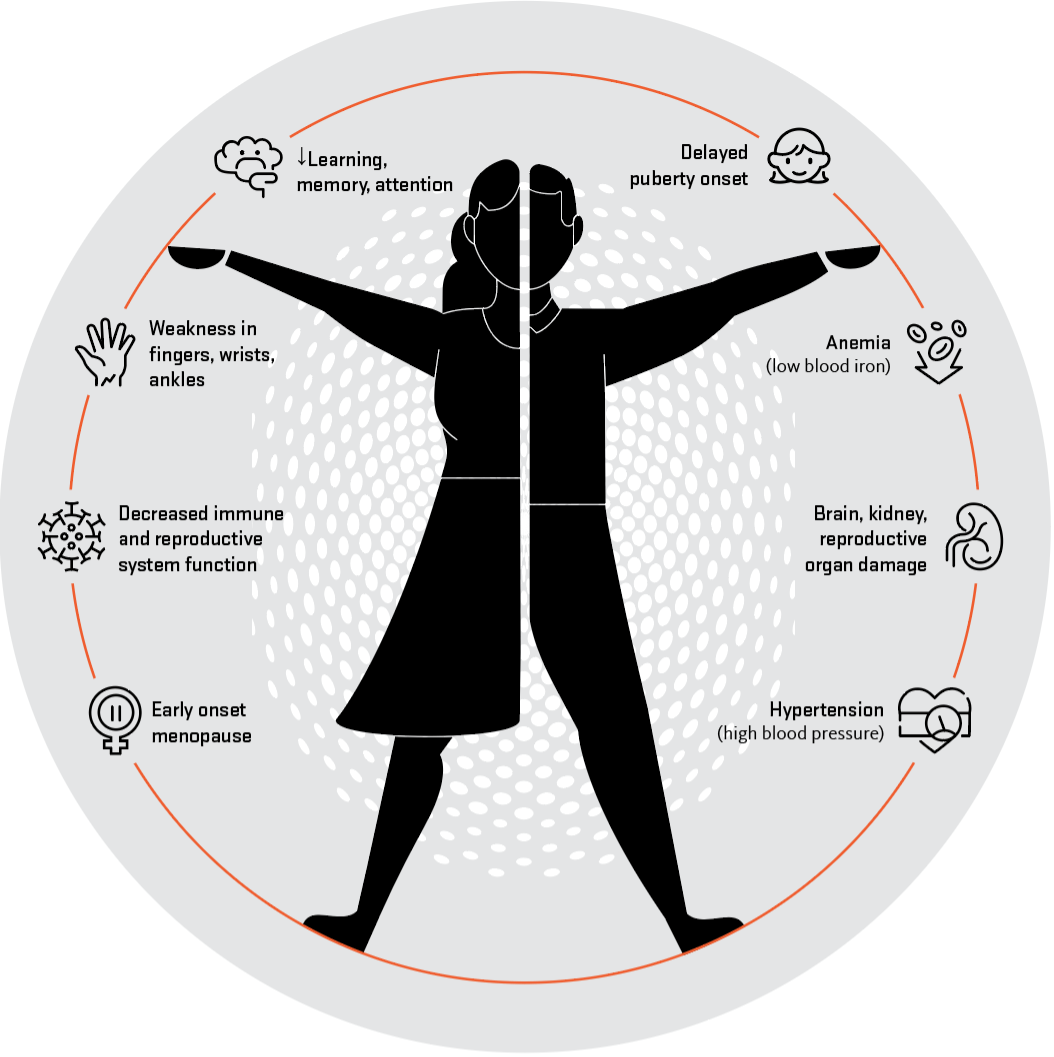

Lead can increase the risk of these health effects:

- Early onset menopause

- Decreased immune and reproductive system function

- Weakness in fingers, wrists and ankles

- Problems with learning, memory and attention

- Delayed puberty onset

- Anemia (low blood iron)

- Damage to the brain, kidneys and other organs

- High blood pressure

Lead can increase the risk of these health conditions in children:

- Delays in mental development (learning, intelligence, behavior)

- Attention-related behavioral problems

- Delays in physical growth

- Seizures

- Hearing loss

- Hypertension

- Anemia

- Severe stomachaches

- Muscle weakness

- Kidney and brain damage

During pregnancy, lead can increase the risk of these health conditions:

- Premature birth

- Reduced fetal growth

- Low birth weight

- Miscarriage

- Preeclampsia

- Poor kidney function

- High blood pressure

- Anemia

For more details, visit the Agency for Toxic Substances and Disease Registry. Reach out to your health care provider if you are concerned about lead exposure.

Testing options

Where can you get your water tested?

To find accredited labs in Oregon, visit the Oregon Health Authority.

The laboratory will supply a water collection kit with instructions on how to collect, store, and send your water sample.

How much will a test cost?

The test will cost between $30 and $45.

Be sure to contact several labs about price and logistics before ordering tests.

If you have a treatment system, test treated water at least once a year.

How do you test for lead?

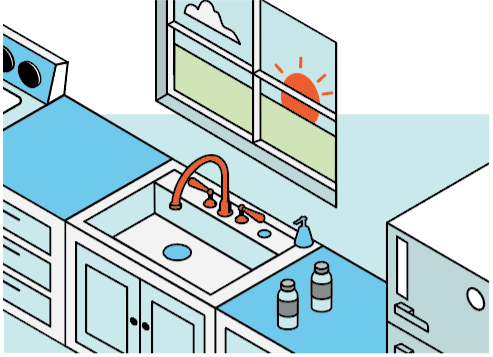

Collect two water samples from the kitchen faucet:

“First-draw” sample. Collect the first-draw sample first thing in the morning from cold water that has sat in the plumbing system overnight.

“Running” sample. Collect the running sample after allowing the cold water to run for one minute.

Compare the results. If lead levels are higher in the first draw sample than the running sample, this suggests that lead comes from your household plumbing. If lead levels remain high after the water has run for one to two minutes, this suggests that lead is present in the water before it enters the household plumbing. The lead may come from water supply contamination or from the well pump or galvanized casing.

Why would you collect multiple water samples?

Two samples can identify the source of lead. A treatment system at the well will not be effective if the lead comes from the household plumbing.

| Lead level | Water usage | Recommendation |

|---|---|---|

| Up to 1 part per billion (µg/L) 0.001 mg/L | SAFE for all uses | |

| Up to 15 ppm (µg/L) 0.015 mg/L | Not recommended for infant formula or baby food. Pregnant women, immunocompromised people, and young children should avoid drinking untreated water. Don’t use untreated water for cooking, in beverage mixes, in food preparation or for washing fruits and vegetables. | Run COLD tap water for 1 to 2 minutes before using it for drinking or cooking. |

| 15 ppb (µg/L) 0.015 mg/L | Public water system limit. If this were a public water supply, the public water system would be actively treating the water to reduce the lead level. | |

| More than 15 ppb (µg/L) 0.015 mg/L | NOT SAFE for consumption by humans, pets, or livestock (including drinking, mixing into beverages, cooking, washing fruits and vegetables). SAFE for other household uses (bathing, washing dishes, laundry, garden irrigation). | Treat contaminated water. See ACTION STEPS FOR CONTAMINATED WATER. Supervise children to ensure they do not swallow water while bathing, brushing teeth, etc. |

| More than 40 ppm (mg/L) | NOT SAFE for consumption by humans, pets or livestock. SAFE for other household uses: bathing, washing dishes, laundry, garden irrigation. | See ACTION STEPS FOR CONTAMINATED WATER. Supervise children to ensure they do not swallow water while bathing. If you have concerns about lead buildup in your soil, follow advice from OSU Extension on getting your soil tested. |

Test results can be reported in ppb (parts per billion), μg/L (micrograms/L), or mg/L (milligrams/L); 1 ppb = 1 μg/L = 0.001 mg/L

Action steps for contaminated water

If your water has elevated lead levels, the safest thing you can do is use treated water or

bottled water for:

- Drinking

- Cooking food such as pasta and rice

- Washing and cooking fruits and vegetables

- Mixing juices, coffee, and tea

- Infant formula

- Brushing teeth

Only use bottled water if the label says it has been purified.

Lead is not readily absorbed through the skin. It is generally safe for adults to use water that contains lead (up to 500 ppb) for:

- Showering or bathing

- Washing laundry

- Cleaning dishes

Levels below 15ppb

If you need to use your water that has lead levels below 15ppb, try running the water on COLD from the faucet before using the water for drinking or cooking. If you recently used water, run the cold water for at least 30 seconds. If the water has been sitting in household plumbing without use for six hours or more, let the cold water run for two minutes or longer.

Check for corrosion

Homeowners who have a well with a submersible pump may want to have the pump checked. If some of the pump’s metal parts are corroding, they could be contaminating the groundwater with lead.

Acid-neutralizing filters can be installed to reduce water corrosivity by adding calcium and by increasing the pH of the water. Unlike other treatment options, these filters act to prevent lead from entering the water rather than removing it at the tap. However, these units normally cost over $1,000 and may cause a noticeable increase in the hardness of your water.

Treatment systems

Install a water treatment system to remove lead from your home drinking water. Carbon filtration, distillation, or reverse osmosis systems can be effective for lead removal. These systems require careful maintenance for effective operation. See the water treatment guide for more information about treatment.

Treatment systems require careful maintenance for effective operation. If a treatment system is installed, you must continue to test your treated water for lead every year to ensure it is working correctly.

| Contaminant | Recommended water treatment systems | Additional treatment systems may be required if multiple contaminants are present | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Anion exchange | Reverse osmosis | Distillation | Aeration and filtration | Carbon filter | Chlorination | Oxidizing media filtration | Ozonation | Ultraviolet (UV) distillation | Water softener | |

| Lead | Removes or partially removes | Removes or partially removes | Only if the filter includes absorption media rated by National Sanitation Foundation | |||||||

| Arsenic | Removes or partially removes | Removes or partially removes | Removes or partially removes | May be needed for pretreatment to remove arsenic | May be needed for pretreatment to remove arsenic | May be needed for pretreatment to remove arsenic | ||||

| Nitrate | Removes or partially removes | Removes or partially removes | Removes or partially removes | |||||||

| Color, taste or odor issues | Removes or partially removes | Removes or partially removes | Removes or partially removes | Removes or partially removes | Removes or partially removes | Removes or partially removes | Removes or partially removes | Removes or partially removes | ||

| Bacteria and viruses | Removes or partially removes | Removes or partially removes | Removes or partially removes | |||||||

| Calcium and manganese (water hardness) | Removes or partially removes | Removes or partially removes | Removes or partially removes | |||||||

| Chlorine | Removes or partially removes | Only if the filter includes absorption media rated by National Sanitation Foundation | ||||||||

| Hydrogen sulfide | Removes or partially removes | Only if the filter includes absorption media rated by National Sanitation Foundation | Removes or partially removes | Removes or partially removes | Removes or partially removes | |||||

| Sulfate | Removes or partially removes | Removes or partially removes | Removes or partially removes | |||||||

| Iron | Removes or partially removes | Removes or partially removes | Removes or partially removes | Removes or partially removes | Removes or partially removes | Removes or partially removes | ||||

| Radon | Removes or partially removes | Only if the filter includes absorption media rated by National Sanitation Foundation | ||||||||

| Uranium | Removes or partially removes | Removes or partially removes | Removes or partially removes | |||||||

| Pesticides | Removes or partially removes | Removes or partially removes | Only if the filter includes absorption media rated by National Sanitation Foundation | |||||||

| Perfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS) | Removes or partially removes | Only if the filter includes absorption media rated by National Sanitation Foundation | ||||||||

| Trichloroethylene (TCE) and other volatile organic compounds (VOCs) | Removes or partially removes | Removes or partially removes | Only if the filter includes absorption media rated by National Sanitation Foundation | |||||||

Adapted from Home Water Treatment Fact Sheet, Minnesota Department of Health

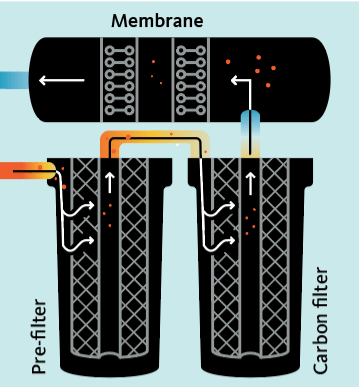

Reverse osmosis

Reverse osmosis uses energy to push water through a membrane with tiny pores. The membrane stops many contaminants while allowing water to pass through.

Pros: Removes a wider variety and greater amount of contaminants than many other treatment options.

Cons: Can create a lot of wastewater. May require pretreatment to prevent the membrane from getting clogged.

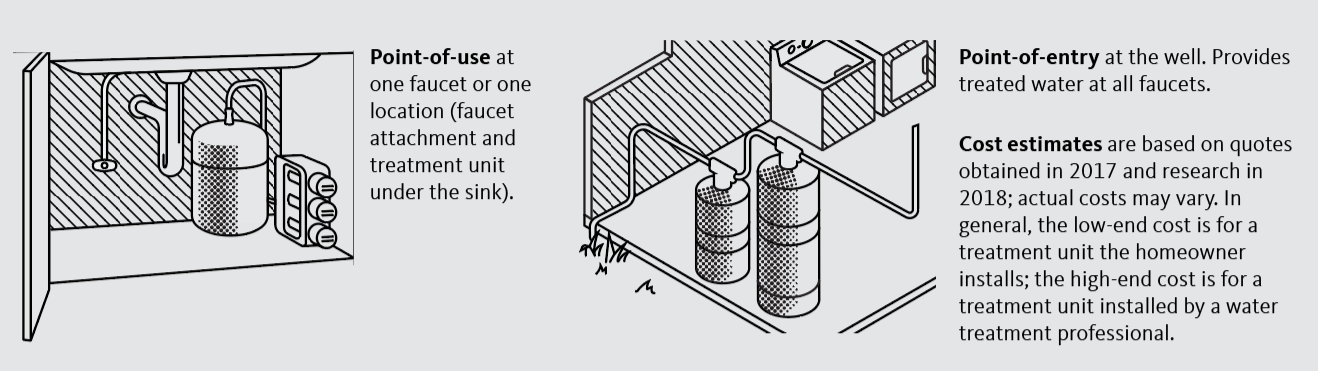

Point-of-entry cost estimate

- Initial: $5,000–$12,000

- Maintenance: $250–$500 every one to two years

Point-of-use cost estimate

- Initial: $300–$1,500

- Maintenance: $100–$200 every one to two years

Distillation

Distillers boil water, which makes steam. The steam rises and leaves contaminants behind. The steam hits a cooling section, where it condenses back to liquid water.

Pros: Removes a wider variety and greater amount of contaminants than many other treatment options. Kills 100% of bacteria, viruses, and pathogens, so you can still drink your water during boil-water advisories or if your well becomes contaminated.

Cons: Heating the water to create steam can be expensive. Water may taste “flat” because oxygen and minerals are reduced.

Point-of-entry cost estimate: N/A

Point-of-use cost estimate

- Initial: $300–$1,200

- Cost consideration: Energy to boil water

Carbon filter

Contaminants accumulate on the filter while water passes through. This includes granular activated carbon filters.

Pros: Point-of-use carbon filters are inexpensive and easy to find and use.

Cons: This method only removes a small amount of lead. Harmful bacteria can grow if you do not regularly maintain and replace the filter according to the instructions. If the filter is not replaced according to the instructions, it can become saturated and begin to release contaminants into the water.

Point-of-entry cost estimate

- Initial: $500 to $3,000

- Maintenance: Extra water to backwash or adding a disinfectant to kill bacterial growth. Replacement of the filter.

Point-of-use cost estimate

- Initial: $300 to $1,200

- Cost consideration: energy to boil water

How do you know the treatment system will actually work?

The following organizations certify water treatment systems:

You can search these databases by manufacturer or chemical contaminant. Often manufacturers will report the

effectiveness by percent removal (the amount of contaminant that is removed from the water).

What are the financial considerations?

You can purchase and install a treatment unit on your own, or you can work with a treatment professional.

An alternative to water treatment is using a water delivery service or bottled water. This can be a cost-effective solution for some people. Please note that bottled water is not regulated to the same standards as tap water. Water labeled as “artesian” may not be treated. Only use bottled water if the label says it has been purified by reverse osmosis or distillation.

For more information, see EPA Bottled Water Basics.

Your household may also qualify for a loan (which you have to pay back) or grant (which you do not have to pay back) to help pay for water treatment. Visit OSU's well water program for information about loans and grants.

What should you consider when choosing bottled water?

Note: Beware of false claims, deceptive sales pitches, inaccurate water quality data, and scare tactics used by some water treatment companies to sell expensive and unnecessary home water treatment units. Here are some recommended questions to ask a water treatment professional.

What if your water contains multiple contaminants?

Select the appropriate treatment for the contaminant you are trying to control. No single treatment unit can remove all contaminants from water, but some units can remove multiple contaminants.

How do you find a certified water quality professional?

Search listings in your telephone book, online or at Find Water Treatment Providers.

If you work with a treatment professional, work with a licensed pump contractor or a licensed plumber. You can check this by using the Oregon Building Codes Division’s License Holder Search.

Acknowledgment: Funding was provided by the National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences (NIEHS grant #R01 ES031669), an institute of the National Institutes of Health.