Smoke is important to consider when planning a prescribed burn. Besides reducing visibility, smoke can affect firefighter and public health and safety. Address these concerns by making sure that prescribed burns take place under conditions that limit unintended smoke impacts.

What are smoke emissions and how are they produced?

Smoke is a mixture of water vapor, gases, fine particles and trace minerals from burning fuels like trees, vegetation and other organic components. Water vapor and carbon dioxide make up 90% of smoke from prescribed fires. Smoke occurs when there is not enough oxygen present to completely combust the fuel.

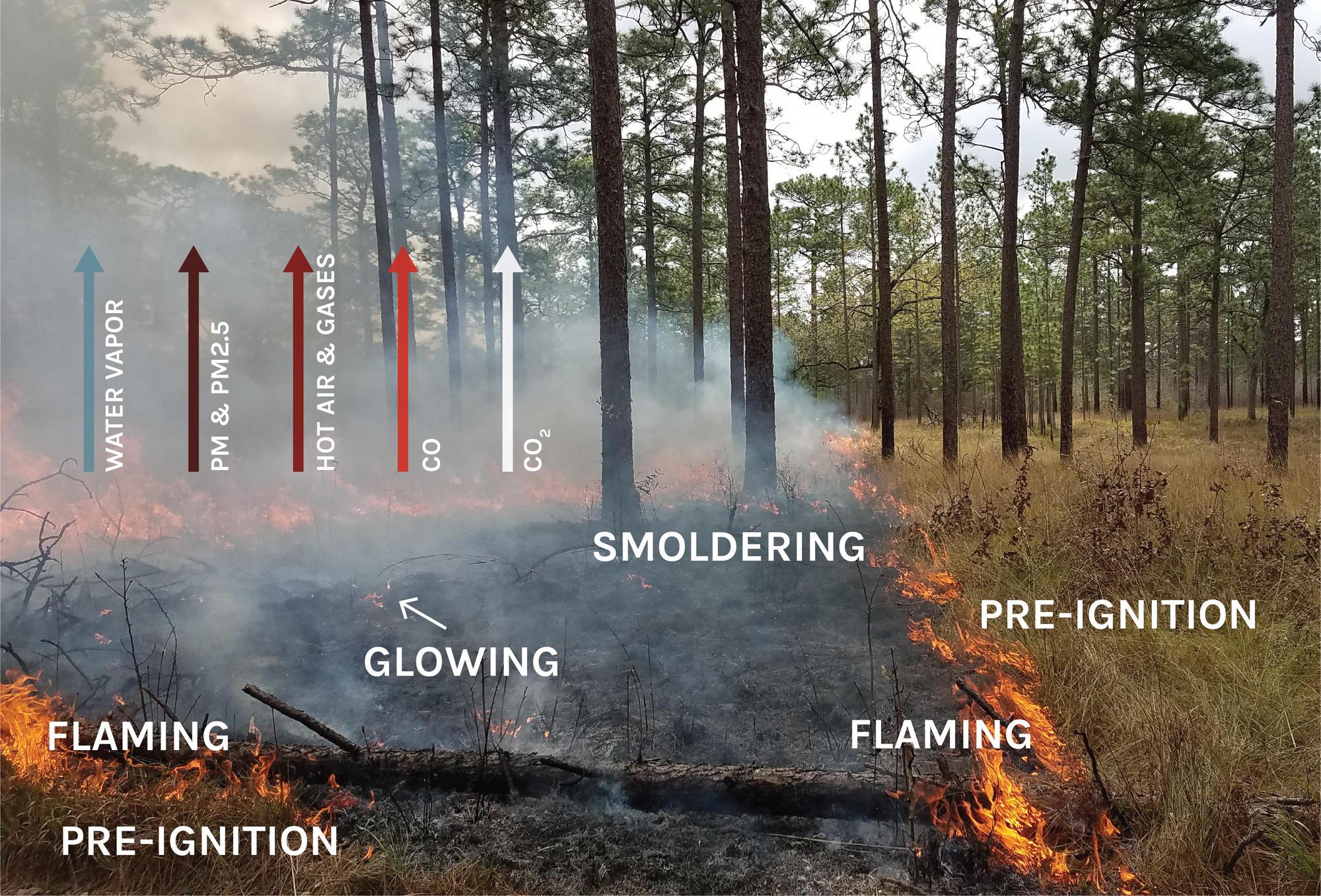

There are four main stages of combustion during a prescribed burn. Each stage produces different smoke emissions that can affect health and safety.

- Preignition and flaming stages: These stages produce less particulate matter (soot and tar) because flames efficiently consume the fuels.

- Smoldering stage: Fire in this stage produces large amounts of particulate matter. Heat is lower, and fuels are not consumed as efficiently. Smoke from the smoldering phase often stays near the ground, further affecting air quality.

- Glowing stage: Glowing fires produce carbon dioxide and carbon monoxide, which are colorless and odorless gases.

The longer fuels are in a flaming stage, the more complete the combustion. When combustion is inefficient, with a short flaming stage and a long smoldering phase, fires produce more particulate matter.

Over 90% of the particulate matter produced by prescribed fires is small enough to pass through the lungs. These particles, less than 10 microns in diameter, can potentially cause heart and lung problems and eye irritation. It is important to burn under weather and fuel moisture conditions that maximize combustion efficiency to help reduce smoke impacts.

What contributes to smoke impacts?

Smoke impacts are generally created by a number of conditions, including:

- Wet fuels.

- Light winds.

- High relative humidity and inversion layers.

- Cold overnight temperatures.

- Wind shifts.

- Weather fronts.

An important step in smoke management is to recognize these conditions and minimize burning when they are present. Cold overnight temperatures, stable air, high relative humidity and low wind speeds are some of the most critical factors.

Stable atmospheric conditions create smoke problems because of low wind speeds and inversion layers that trap smoke close to the ground. Cold overnight temperatures tend to bring smoke to the ground level, sometimes compounded by higher relative humidity, which also has a direct effect on visibility. In high humidity, atmospheric moisture condenses on smoke particles to produce fog or haze, particularly at night.

Fuel size and moisture are the primary fuel characteristics that affect emissions. Larger fuels, such as logs or coarse wood, are less likely to be completely consumed during the flaming stage. They typically produce more smoke by smoldering. As fuel moisture increases, more heat is necessary to release the free water as vapor from the fuel to then combust. This, in turn, leaves less energy to complete combustion, resulting in higher emissions. Less heat from moist fuels can also inhibit smoke dispersion, since the smoke will not rise as high. Fuel conditions that produce more smoke, especially after the flaming phase of combustion, include compact fuels such as duff, large fuels such as logs and stumps (including decaying logs/trees), and overall heavy fuel loadings. These fuels often smolder and produce smoke for days or weeks.

Oregon’s Smoke Management Plan

The Oregon Smoke Management Plan is part of the State Implementation Plan of the Federal Clean Air Act, which aims to minimize smoke emissions from prescribed burning as described by ORS 477.552. The plan intends to provide maximum opportunity for essential forestland burning while protecting public health by avoiding smoke intrusions. It also maintains compliance with state and federal air quality and visibility requirements, and promotes the development of techniques to reduce smoke by encouraging cost-effective use of forestland biomass, alternatives to burning, and emission reduction techniques. The plan requires the state forester and each field administrator to maintain a satisfactory atmospheric environment in populated areas sensitive to smoke and those protected under state and federal laws.

Operational Guidance for the Oregon Smoke Management Plan, which contains information on registering, permitting and monitoring, can be found at the Oregon Department of Forestry.

Objectives for smoke management

Managing smoke to protect air quality includes three basic objectives that should be addressed in the burn plan (See Planning a Prescribed Burn, EM 9343).

Smoke management is used as a part of prescribed burning to minimize smoke impacts to human health, safety and visibility in federally protected areas. The three primary objectives, as described in both the National Wildfire Coordinating Group Smoke Management Guide and the Oregon Smoke Management Plan, are:

- Screen for and avoid smoke-sensitive areas, such as towns, special events, highways and airports.

- Reduce emission output for each unit area treated.

- Disperse and dilute smoke before it reaches smoke-sensitive areas.

The Oregon Department of Forestry limits the number of burns that can happen at a given time in a given area. ODF issues daily burn forecasts and instructions based on predicted weather, and determines where, when and how much fuel landowners can burn each day. This ensures that smoke is limited, diluted, and avoids impacting smoke-sensitive areas. Written burn plans should address smoke management, identifying areas sensitive to smoke and ways to minimize impacts.

| Basic smoke management practices | Benefits | When to apply for the prescribed burn |

|---|---|---|

| Evaluate smoke dispersion conditions | Minimizes smoke impacts | Before, during, after the burn |

| Monitor smoke impacts on air quality | Minimizes smoke impacts on air quality | Before, during, after the burn |

| Keep a smoke journal | Helps inform future burn decisions | Before, during, after the burn |

| Notify nearby communities and neighbors | Allows residents to prepare for temporary smoke conditions | Before, during the burn, after the burn |

| Consider emission reduction techniques | Reduces emissions and downwind impacts | Before, during the burn |

| Coordinate burns with other burns in the airshed | Manages exposure of the public to smoke | Before, during, after the burn |

Credit: USDA-NRCS, O'Neill, Susan, Pete Lahm. 2011. Basic Smoke Management Practices. USDA Natural Resources Conservation Service.

To minimize emissions and maximize smoke dispersion and dilution, combine favorable fuel and weather conditions with the right ignition devices and patterns, in addition to following basic smoke management practices. For example, maintaining fuels in the flaming phase improves combustion and produces less particulate matter. One way to achieve this is to adjust the pattern of ignition so that fires are backing into the wind, which allows for more flame residence time and produces less particulate matter. In general, the higher the rate of spread, the less complete the combustion process.

Smoke dispersion is a key component of effective smoke management. Dispersion refers to the atmospheric processes and characteristics that mix and transport smoke. Good smoke dispersion requires enough convection to lift smoke into upper level winds that carry it away from smoke-sensitive areas.

Smoke management also requires effective public relations

Effective communication plans provide timely, accurate, locally relevant and advance notification about planned prescribed fire and potential smoke impacts. This kind of outreach is a key factor in local support for prescribed fires.

Prescribed fire should employ simple and clear communications strategies that describe:

- The purpose and importance of prescribed fire.

- Its timing and location.

- Strategies to reduce emissions.

- The health impacts of smoke.

- Recommendations to reduce exposure to smoke and mitigate its health impacts.

This can be part of a larger outreach strategy outlined in the burn plan. Examples of outreach include notifying neighbors, posting social media updates, notifying emergency management services and posting signs to alert the public to the planned nature of the burn and potential for impacts from smoke.

Glossary

Air quality — The quantity and type of pollution in the air.

Atmospheric stability — The likelihood of turbulence in the atmosphere.

Class 1 Area — An area defined under the Clean Air Act where visibility is stringently protected. Examples include national parks and wildnerness areas.

Consumption — How much fuel of a specific type burns. Example: 13% of preburn weight was consumed.

Dispersion — How much pollutants decrease in concentration as they spread through the atmosphere.

Emission rate — The quantity and speed at which smoke is emitted. Emission rate = available fuel x burning rate x emission factor.

Particulate matter — Small particles of solids or liquids suspended in air.

Flaming combustion — Fuel burns rapidly and produces visible flames. White smoke is made up of soot, tar and a high composition of water vapor. Combustion is relatively efficient.

Smoldering combustion — Follows flaming combustion. Emissions double those in flaming combustion.

Glowing combustion — Final phase of combustion. Solid fuel is oxidized and fire glows. No visible smoke.

References

Campbell, J.H., J.E. Fawcett, D.R. Godwin, and L.A. Boby, 2020. Smoke Management Guidebook for Prescribed Burning in the Southern Region. University of Georgia Warnell School of Forestry and Natural Resources. Outreach Publication WSFNR-20-91A (Nov 2020).

Hardy, Colin C., Roger D. Ottmar, Janice L. Peterson, John E. Core and Paula Seamon, eds. 2001. Smoke Management Guide for Prescribed and Wildland Fire: 2001 edition. PMS 420-2. NFES 1279. Boise, ID: National Wildfire Coordination Group.

Resources

- USFS-NRCS guide to Basic Smoke Management Practices

- National Weather Service Fire Weather Forecasts

- National Weather Service Fire and Smoke Mapping Resources

- EPA AirNow! Air Quality Observations and Forecasts

- National Wildfire Coordination Group Smoke Management Guide for Prescribed Fire and Wildland Fire

- Introduction to Prescribed Fire in Southern Ecosystems, U.S. Forest Service

- Smokepedia

Acknowledgments

This publication is part of a series developed by the Forestry and Natural Resources Extension Fire Program. The program would like to acknowledge contributions from Chris Adlam, southwest regional fire specialist; John Punches, Extension Forestry and Natural Resources faculty and associate professor; and John Rizza, northeast regional fire specialist.