Water is one of Oregon’s most critical natural resources. As the state’s population increases and urban areas expand, water use and water rights are becoming increasingly contentious issues. Landscape plantings are a valuable part of residential properties and require some amount of water. Maintaining your landscape is important for property values as well as aesthetic reasons. When water supplies are restricted, you can keep your landscape healthy by developing watering priorities, applying water efficiently, and modifying your maintenance practices.

A longer-term drought might encourage you to re-evaluate your yard. Look for plants in the wrong location (azaleas on the south side of a building, for example), plants that are not adapted to Oregon’s dry summers, or plants that are not growing well or show signs of disease. These plants often will perish during severe drought. Their demise can give you the opportunity to replace them with more suitable species.

Keys to a water-efficient landscape

When installing a new landscape and maintaining an established one, there are several things you can do to reduce the amount of water it will need. Many of these suggestions are based on the concept of “xeriscaping,” a term coined in the 1980s to describe water-efficient landscaping. Key steps to a successful water-efficient landscape include:

- Start with a landscape plan.

- Improve your soil before planting.

- Select appropriate plants.

- Get your plants off to a good start.

- Water wisely and prioritize your watering

- Take care of your plants.

Research has shown that these water-saving guidelines can reduce landscape water use by 35 to 75 percent.

Start with a landscape plan

A water-efficient landscape begins with a plan. If you are familiar with the principles of landscape design, you might want to draw your own plan. Another option is to hire a professional to help with this critical step. In any event, think about who will use your landscape (adults, children, pets), how the landscape will be used (formal entertaining or informally), and what existing elements you want to keep.

In your design, group plants based on the amount of water they need. This will prevent you from overwatering the drought-tolerant species and underwatering those that need more water.

For patios or walkways, use permeable materials—such as stone or open-cell concrete pavers—that allow water to soak into the soil. Another option is to grade the site so that runoff is redirected into landscape features, such as a rain garden, where plants can use it.

Improve your soil before planting

Most new residential sites have very poor soil. During construction, most of the topsoil is removed, the remaining soil is compacted by heavy equipment, and construction rubble is buried. A soil test will tell you whether nutrients are lacking. Dollar for dollar, soil improvement is the best investment you can make to ensure healthy plants and water conservation.

Organic matter such as compost or shredded leaves adds nutrients, increases the soil’s ability to absorb and store water, and increases air spaces in the soil. As a result, plant roots penetrate the soil more easily and grow deeper. In addition, water soaks into the soil instead of running off the surface.

For tree, shrub, and flower beds, till 2 to 4 inches of organic matter into the entire planting area rather than amending individual planting holes. This will create a better environment for root growth and establishment.

Turfgrass grows well in most soil types. In sterile, sandy soils, an organic soil amendment will help with initial establishment. As long as the existing soil is tilled to a depth of 8 inches, turf should grow well. To prevent runoff, make sure the final grade doesn’t slope steeply toward a road or sidewalk.

Select appropriate plants

Many sources list low-water-use or droughttolerant plants, but the criteria used in developing these lists vary greatly. The most important criterion is to select trees, shrubs, groundcovers, and perennials that are adapted to your region’s soil and climate.

A good idea is to look for plants that are native to your area. However, just because a plant is native does not necessarily mean it is droughttolerant. Likewise, many nonnative plants are well adapted to our region. In general, species native to Mediterranean climates are suitable for western Oregon. In eastern and central Oregon, plants native to the Intermountain West may make good choices.

Most turfgrass species used in Oregon have similar water requirements. Ecolawns are a lowwater alternative to traditional turf. They contain a mix of broadleaf plants (clover, yarrow, English daisy, and others) and grasses (generally perennial ryegrass). Ecolawns provide many of the benefits of traditional turf, including recreation, dust and noise abatement, and temperature moderation, but require less irrigation.

Note: It is very difficult to establish a new lawn during a drought. The soil needs to be kept moist as the grass germinates, and the new lawn will need water almost daily at first. It’s much better to wait until the rainy season or until you have adequate water supplies for irrigation.

Get your plants off to a good start

Choose healthy plants and plant them correctly to get your water-wise garden off to a good start. Consult a nursery, your local Extension office, or reference books for planting instructions. All plants require supplemental water as well as extra attention during the first, second, and possibly the third growing season.

Water wisely

People waste water; plants don’t. Landscape water loss typically occurs in two ways:

- Water is applied too rapidly and runs off the soil surface rather than soaking into the soil.

- Water is applied to bare soil surfaces and evaporates.

- Applying the right amount of water, at the right time, and in the right way is the most important thing you can do to conserve water.

Choose the most appropriate irrigation system

Wise watering involves applying water slowly, deeply, infrequently, and directly to the root system. As a result, water soaks into the soil rather than running off the surface or evaporating. The type of watering system you choose can make a big difference in how efficiently you water.

Tree, shrub, and flowerbeds, as well as vegetable gardens, grown in soils with higher levels of organic matter are most effectively irrigated with drip or trickle systems. Some drip systems have individual emitters spaced along a hose. Soaker hoses, on the other hand, slowly release water along their entire length. Another option is a garden hose with a slow stream of water. For larger trees and shrubs, you will need to move the hose around in order to get good coverage. This technique might take several hours for large trees. Another option is to apply water below the soil surface. Punch holes in the bottoms of juice or coffee cans and push the cans 6 to 12 inches into the soil. Fill the cans with water. The water will seep out the bottom into the soil directly surrounding the plant roots. This method can greatly reduce evaporation and unnecessary wetting of surrounding soil. For plants growing in sandy soils, a better option is to use microspray emitters or a pop-up-type irrigation system. While not as efficient at conserving water as a drip system, they provide even, consistent coverage that is needed for plants to thrive in sandy soils.

Hose-end attached sprinklers are much less efficient because they lose water to evaporation and may apply water to areas where it is not needed. In some cases, like lawns, sprinklers might be the only alternative.

Automated sprinkler systems are especially prone to encouraging waste and require proper attention and management. Studies show that people with automated underground irrigation systems use up to twice as much water as those watering manually with hoses and sprinklers. The convenience of an automated system may make it easy to overwater because you pay less attention to your irrigation. Test your sprinkler output at different locations in the garden using a rain gauge.

Maintain watering equipment

To maximize efficiency, keep equipment in good shape. This is especially important with automatic sprinkler systems. Repair or replace broken or damaged nozzles or heads, ensure that the timing mechanism and rainfall shutoffs are working, and make sure you know how much water is being applied. Check your system weekly and adjust the days and run times as needed to avoid overwatering.

Water infrequently and deeply

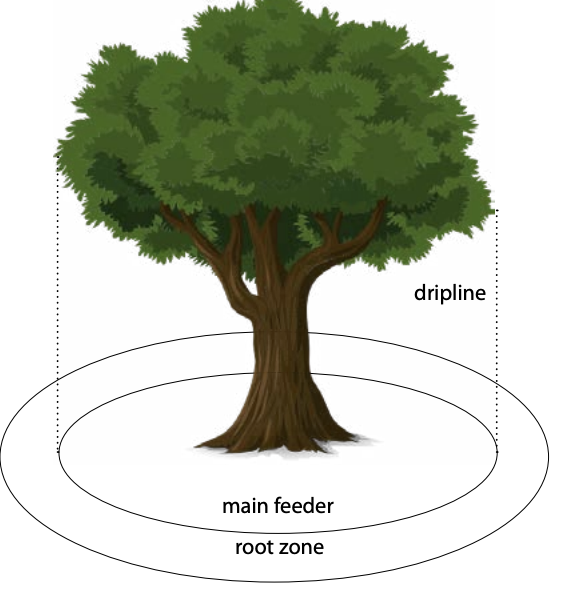

Where to water: The majority of feeder roots (those that take up water and nutrients from the soil) are in the top 12 inches of soil and extend as much as 11/2 times past the canopy diameter of tree and shrubs (Figure 1). To be most effective, apply water in this area.

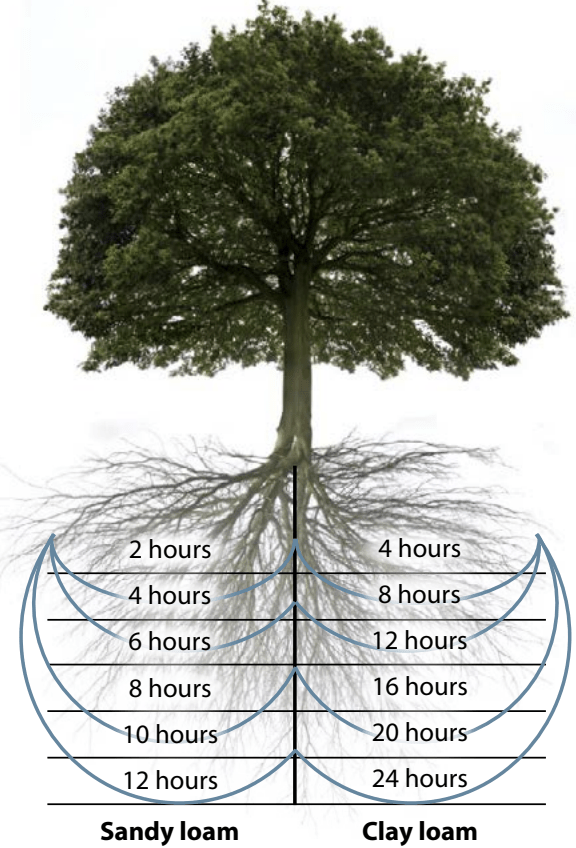

Irrigate plants infrequently and deeply prior to and during drought: By thoroughly soaking the root zone, you will encourage roots to develop deep in the soil, where moisture is held for a long time. These deep roots will help the plant endure drought better. The goal is to saturate the area to a depth of 8 to 10 inches. Your soil type will affect how quickly water moves through the soil and watering large trees and shrubs can take several hours (Figure 2). Frequent, shallow watering encourages plants to develop shallow root systems, which makes them susceptible to even moderate water shortages. As the growing season progresses and your plants develop deep roots, you can gradually lengthen the time between watering.

Water at night or in early morning

Less water is lost to evaporation early and late in the day when temperatures are lower, humidity is higher, and the air is calmer. The disadvantage of watering before or after daylight is that you won’t see your system operate, so you will not know if you are overwatering or underwatering unless you check your plants, soil, and output periodically

Watering priorities

Newly planted trees, shrubs, groundcovers, and lawns

Newly established plants require more water than established plantings because the root systems are shallow. It may be unavoidable, but consider delaying new plantings during drought periods to help conserve water. Most newly transplanted trees, shrubs, and groundcovers need at least 1 inch of water per week during the growing season (June through September) and during other dry periods in the winter.

How much and how often are the two biggest questions associated with watering newly established lawns. Newer lawns are less able to withstand drought than well-established lawns. To maintain a lush, green lawn, apply 1 to 11/2 inches of water per week during the dry season. For most soil types, you should water one to three times per week in order to apply the right amount of water and avoid runoff from applying too much water too quickly. Use a rain gauge to determine how much water your irrigation system is applying and adjust irrigation duration.

Established landscapes

During a drought, consider strategically watering your established landscape. Select small, important areas within your landscape to water regularly. Allow peripheral areas of your lawn, or those that aren’t highly visible, to go dormant by watering less.

Trees: As trees increase in size, they become increasingly valuable. Mature trees usually receive supplemental water when you water shrubs or lawn areas. If you water your shrubs less and let your lawn go dormant during times of water restrictions, you might want to water your trees deeply every 2 weeks or so. Prematurely shedding leaves are a sign of drought stress. If your trees begin dropping leaves, increase your watering frequency.

Shrubs: Well-established, healthy shrubs contribute significantly to the overall landscape. These plants should be second in priority for watering. To conserve water, consider removing shrubs that are overgrown, unhealthy, or in the wrong place.

Perennial plants: Your next priority should be large perennial areas or individual plants that had a high initial cost. Perennials require less water than trees and shrubs. Mulch the bed to reduce soil moisture evaporation.

Annual bedding plants: These plants have a relatively high water requirement compared to perennials. In times of severe drought, you might want to forego annual plantings and instead apply a 3- to 5-inch layer of mulch to your annual beds. After the drought has passed, plant the area the following year.

Containers: Plants in containers dry out more quickly than those in the ground. During a drought, you might want to reduce the number of container plants you grow.

Lawns: In general, the healthier the turf is when drought stress begins, the longer it will stay green and the better it will weather the drought. Many people water their lawn more than necessary. As a result, lawns have a reputation for using a lot of water. Instead of following a predetermined watering schedule, observe your turf and check the soil moisture regularly. You then can alter your watering schedule to better meet the needs of your lawn. The key is to apply only as much water as the turf actually requires.

Initial signs of drought stress include wilting and discoloration of the grass. To check soil moisture of clay-type soils, insert a screwdriver into the soil. If it penetrates the soil easily, the soil is moist. If it requires effort, the soil is getting dry.

During drought, consider watering half as much as usual. Many turfgrass varieties, including fescues, are relatively drought-resistant. Lawns will stay mostly green with some localized brown spots if they receive 1/2 to 3/4 inch of water per week (more water may be required with lawns planted in full sun). Watering once or twice a week to apply this amount of water should be sufficient. Use a rain gauge for accuracy. Another option is to not water at all and allow the turf to go dormant and turn brown during the summer. Be sure to give your lawn proper care before and after the drought.

Landscape maintenance

Additional steps can be taken to reduce the amount of water that your garden or landscape requires.

Mulch

A 3- to 5-inch layer of mulch can reduce soil water evaporation by 70 percent compared to bare soil. Mulch also reduces soil temperature, prevents soil compaction, improves water infiltration, reduces runoff, and suppresses weed growth. When you water, make sure the water penetrates through the mulch and reaches the soil.

Both organic and inorganic mulching materials are available. Examples of inorganic mulches include lava rock, river rock, and landscape fabrics. Landscape fabrics often are used beneath rock or organic mulch to inhibit weed growth. Landscape fabrics are not black plastic. Like plastic, they block light, thereby suppressing weed growth. Unlike plastic, however, they allow water and air to pass through to the soil.

Organic mulches come in different particle sizes. Mulches with small particles include sawdust, decomposed compost, and grass clippings. A 2- to 3-inch layer of these products is sufficient and allows for air exchange between the soil and atmosphere.

If you use grass clippings, make sure the lawn wasn’t treated with a broadleaf weed (e.g. dandelion) herbicide and that the clippings have dried out before you apply them. A thick layer of fresh grass clippings can mat down, get slimy, smell bad during decomposition, and prevent air from reaching the soil. To avoid these problems, apply only a 3⁄4- to 1-inch layer. A better use of grass clippings is to use a mulching mower that chops them up and leaves them on the lawn where they can decompose and return nutrients to the soil.

Mulches with large particle sizes include shredded bark, bark chips, bark dust, and conifer needles. You can apply these mulches 3 to 5 inches deep since they don’t readily decompose or compact. Bark chips are one of the most desirable mulches since they are long lasting.

Apply mulch evenly and leave a few inches bare around the stem or trunk of the plant. This space will allow for air circulation around the base of the plant and help avoid disease problems.

Pruning

New trees and shrubs generally need minimal pruning just to remove diseased or broken limbs. For established plantings, heavy pruning during late winter or spring stimulates new growth and increases a plant’s susceptibility to drought. In the spring, remove only dead or diseased branches. If soil moisture is extremely scarce during the summer, you might consider careful, selective pruning to remove leaf area. Prune in such a way that inner, shaded leaves won’t be sunburned, and don’t remove too much plant material or you might stimulate new growth.

Mowing

New lawns need regular mowing (once a week during the growing season if necessary) to maximize turf density and prevent excess evaporation from the soil surface. For specific mowing height guidelines of the grass variety in your lawn see Practical Lawn Care of Western Oregon (EC 1521). Mow at the upper end of the range to encourage maximum root development, which will slightly improve drought tolerance.

It usually is not necessary to dethatch or aerate a new lawn until its second year. Dethatching and aerating established turf will help it develop a deeper root system and make it better able to withstand drought.

Fertilizing

Proper fertilizing can conserve water. Overfertilization can stimulate new, lush growth that increases a plant’s demand for water. If not enough water is available to meet this demand, then the plant will suffer drought stress. Also, heavy fertilizer applications increase the salt concentration in the soil and make it difficult for plants to use whatever moisture might be available. During a water shortage, reduce or eliminate fertilization of trees and shrubs. As a result, the plants will grow more slowly and use less water. For lawn-specific guidelines, see Fertilizing Lawns (EC 1278) in the OSU Extension catalog.

For more information

For more information The following publications are available in the Oregon State University Extension catalog

Harvesting Rainwater for Use in the Garden, EM 9101

Improving Garden Soils with Organic Matter, EC 1561

Practical Lawn Care for Western Oregon, EC 1521

Selecting, Planting, and Caring for a New Tree, EC 1438

Sustainable Gardening: The Oregon-Washington Master Gardener Handbook, EM 8742

A Guide to Collecting Soil Samples for Farms and Gardens, EC 628

Laboratories Serving Oregon: Soil, Water, Plant Tissue, and Feed Analysis, EM 8677