The Persian, or English, walnuts (Juglans regia) grown commercially in Oregon evolved in the mountainous regions of central Asia. California is a world leader in walnut production and produces 99% of the United States walnut crop. This publication is designed for those who grow walnuts commercially in Oregon, as well as for homeowners with walnut trees.

Whether growing walnuts commercially or on a home site, choose a site that has full sun and is free of frost pockets. Walnuts can grow on hillsides or at ground level if the soil is deep and well drained.

Use an auger or posthole digger to determine whether the soil is at least 6 feet deep. A few feet beneath the surface, you may find solid rock or compact subsoils with a mottled color, indicating poor aeration and drainage. With few or no pores large enough for roots to enter, this kind of subsoil layer often supports a water table that restricts root growth. Some surface soils are underlain by loose gravel and coarse sand, which permit little or no root growth.

High temperatures usually are not a limiting factor in western Oregon. However, occasional temperatures around 100°F may cause sunburn on hulls, dark kernels, kernels with black specks, or even complete failure of kernel development. The effect of high temperatures depends on the time of year when they occur.

When the growing season is unusually cool, thin shells, shell perforation and shriveled kernels can be a problem.

Under the mild climatic conditions of western Oregon walnut-growing areas, trees are slow to attain full dormancy in fall and early winter. As a consequence, early cold periods may severely injure many trees.

Spring frosts damage walnut crops much more frequently than winter freezes injure trees. Varieties that leaf out very early may be injured by spring frosts and should not be considered for Oregon. Even late-leafing varieties such as ‘Franquette’ can be injured by late-spring frosts if trees are located in a frost pocket.

Most walnut varieties may produce a few nuts when trees are 5 or 6 years old, but they are not considered mature or in commercial production until trees are 10 years old. Two-thirds of a ton per acre is considered a good yield for a healthy, mature walnut orchard in Oregon. In a home site, with controlled watering and fertilization, a good tree might yield about 100 pounds of nuts annually. Many produce only half that amount; the variation may be due to variety selection, pollination, fertilization, water, soil type and frost.

Varieties of walnuts

With the decline of the walnut industry in Oregon, there are no local wholesale walnut nurseries. Large quantities of trees for a commercial planting must be shipped from California or grown under contract by a nurseryman. Some retail nurseries do carry walnut trees for a premium price.

‘Franquette’

‘Franquette’ is an old French variety that is the principal walnut historically grown in Oregon. It is popular because of its good shell seal and very light kernel color. ‘Franquette’ trees bloom much later than most varieties and thereby usually escape spring frosts. However, they can be severely injured or killed by winter freezes and can suffer less severe damage even in mild freezes. They come into bearing slowly and are less productive than many other varieties. The nuts vary greatly in size, tending to be small in heavy cropping years. ‘Franquette’ is highly susceptible to walnut blight. Shriveled kernels are more common with ‘Franquette’ than with other varieties.

‘Howard’

This California-bred variety produces on lateral shoots, with medium to large nuts that have light-colored kernels with good quality. The harvest time is slightly before ‘Hartley.’

‘Chandler’

This California variety leafs out at the same time as ‘Howard.’ ‘Franquette’ can serve as a good pollinizer. The large nuts have a looser suture seam than ‘Howard.’

‘Carpathian’

These varieties are genotypes of the English walnut that survive in colder winter climates. They are native to the Carpathian mountains in Asia and were brought to Europe through Persia centuries ago. These are the walnuts to grow east of the Cascades. Some retail nurseries sell ‘Carpathian’ seedlings or a seedling selection such as ‘Idaho Carpathian’ or ‘Cascade.’

‘Hartley’

‘Hartley’ originated in California and generally is not cold-hardy enough for Oregon, except on frost-free hillsides. ‘Hartley’ leafs out 10 to 14 days before ‘Franquette’ and matures its nuts 12 to 14 days earlier. It is more susceptible to spring frosts than ‘Franquette.’ Catkins (pollen-producing male flowers) of ‘Hartley’ often are lost to frost, but female flowers are perfectly timed for pollination by ‘Franquette’ catkins. The tree is moderately vigorous, often with weak crotches. The limbs tend to be flexible and drooping, and the tree is more difficult to train than other varieties. ‘Hartley’ is a moderate to poor producer, with kernels that tend to yellow quickly. ‘Franquette’ is suggested as a pollinizer. ‘Hartley’ is susceptible to walnut blight.

Rootstocks

Because of their vigorous growth, northern California black walnut (Juglans hindsii Jeps.) seedling rootstocks previously were used for Persian walnuts (Juglans regia) grown in Oregon. However, girdling of the wood at the union between the black walnut rootstock and the top, known as “blackline,” has killed many trees after years of production. Blackline is caused by a virus. A thin, black line develops in the graft union and slowly extends around the entire tree until it eventually girdles the tree and kills it.

California nurseries offer walnut trees on ‘Paradox’ rootstock, which is a cross of Persian and northern California black walnut. This rootstock is hypersensitive to blackline disease. The use of black walnut rootstock in Oregon is not recommended.

Rootstocks grown from seed of the ‘Manregian’ varieties do grow vigorously and are not susceptible to blackline. They are the best choice for rootstocks for walnuts in Oregon. Other ‘Carpathian’ seedlings are also used as rootstocks.

Pollination and set of nuts

All walnut varieties will set a full crop of nuts when self pollinated, provided pollination takes place when the female flowers are receptive. Self-pollination means that the pollen comes from male flowers (catkins) of the same variety, but not necessarily the same tree. Inadequate pollination may occur because the catkins shed pollen either before or after the female flowers are receptive. In such cases, it is necessary to plant a pollinizer variety that sheds pollen during the peak period of female blossom receptivity of the main variety.

In some unusually warm seasons, ‘Franquette’ sheds all of its pollen before most of its female blossoms are receptive. The result is low yields. This tendency is especially evident in young ‘Franquette’ trees. As the tree ages, the male and female bloom periods last longer. The older the tree, the more the male and female bloom periods overlap.

Planting

Walnut trees usually are planted about 30 feet apart. Plant trees in early winter, as soon as possible after receiving them from the nursery. The earlier a tree is planted, the more chance it has to develop a working root system before it leafs out in the spring.

Do not let the tree roots dry out before planting; keep them in moist sawdust or peat moss. Dig holes 18 to 24 inches wide and 10 to 12 inches deep. Digging in wet ground with a power auger may compact the sides of the hole. If this happens, break down the edges of the hole to eliminate the compacted area and partially fill the hole.

Prune off any broken roots, and plant the trees so that the uppermost root is 2 to 3 inches below the soil surface. Spread the roots out and press them down into the bottom of the hole. Refill the hole with soil. Tamp the soil firmly around the roots to exclude air pockets.

Do not place chemical fertilizer or barnyard litter in the holes. Trees can be injured or killed by fertilizers placed in planting holes. After planting, head the trees as described under “Pruning and training walnut trees.”

Staking and painting new trees

Staking newly planted trees is necessary because the new wood often is too soft to withstand the wind, especially if the wind usually blows from the same direction. Place 7- to 10-foot stakes on the windward side, 6 to 8 inches from the tree, and tie with strips of burlap, unbleached muslin, or similar material. Loop the strips around the tree, crossing between the tree and stake, and tie firmly to the stake with a double wrap. Use care and recheck occasionally to see that ties are not so tight as to girdle the tree.

To prevent sun scald on the trunks of the new trees, paint the trunks with white, water-based exterior latex paint up to the first scaffold branch. Mix the paint with water to a 70% paint solution. Apply the paint with an applicator or soak a cotton glove in paint and run it over the trunk.

Cultivation

Cultivation sometimes is used in commercial orchards to destroy a cover crop, to control weeds, and to prepare for harvest. The highest concentration of walnut roots is found in the top 3 feet of soil. The amount of moisture in that part of the soil usually is enough to supply the tree’s needs from the last effective rains in the spring until the fall rains begin. In unusually dry seasons, this stored moisture may not be enough. The roots of the cover crop usually penetrate at least half of this depth. A cover crop turned under too late, weed growth, or an intercrop will seriously reduce the amount of moisture remaining for the trees. Unless irrigation is provided, the result will be a stunted tree and a light crop of small nuts.

In home lawns, chances are water will be adequate for a walnut tree. A good, long soaking of the walnut tree is more effective than frequent, shallow watering meant for a lawn. Maintain a clean area under the trees to make harvest easier.

Weed control

Use of chemical herbicides around tree trunks or in tree rows eliminates the need to cultivate or flail mow close to the trees, thus preventing damage to the trunk. If you treat a continuous strip in the tree row, the need for cross cultivation is eliminated. Both pre-emergence and contact herbicides are registered for use in walnut orchards. Consult your Extension agent for current information on herbicides, insecticides, and disease control.

Nontillage orchard management

In commercial orchards, a nontillage management system uses a tractor-driven flail mower between rows to cut weed growth or a cover crop close to the ground, starting in early spring. By the time effective rains are over, the cover is mowed to within 1⁄2 inch of the ground. With such close mowing, the cover crop is shallow rooted and dies in early summer. Perennial weeds remain alive all summer and gradually become dominant. About five flailings per year are needed. Weeds in the tree row are controlled with herbicides.

This system reduces erosion, soil compaction, and mechanical damage to tree roots. Tree roots can grow undisturbed in the more fertile upper 6 inches of soil. A nontillage system also reduces the amount of work needed to prepare for harvest. Under wet conditions, harvesting is much easier on fl ailed ground than on cultivated ground. All equipment should have high flotation tires to avoid creation of wheel ruts or cleat marks.

In a home setting, good lawn maintenance will take the place of cultivation and assure adequate water.

Insect pests

The most troublesome insect pest of walnuts in Oregon is the walnut husk fly (Figure 1). The larval or immature stage of this insect is a maggot up to 3/16 inch long, which feeds in the husk. Larval feeding destroys the husk tissue and stains the nut shell and kernel, thus reducing nut quality.

The husk fly overwinters as a pupa in the soil. There is only one generation per year. Adults often begin emerging in mid- to late July. After emergence and mating, egg laying occurs. The eggs hatch in five to seven days, and the larvae begin feeding on the husk. It takes three to five weeks for the larvae to complete their development. The mature larvae tunnel to the outside of the husk and drop to the ground, where they enter the soil and overwinter as pupae. There often is a second peak of emergence three weeks following the first. The late-emerging flies can produce larvae that feed in the husk well into October.

Control sprays targeting egg-laying female flies are often applied to walnut trees in mid- to late July and again three weeks later for that second emergence peak. See the PNW Insect Management Handbook.

The walnut aphid is pale yellow and lives on the underside of leaves (Figure 2). Large populations in the spring can reduce nut size and therefore should be controlled.

Codling moths rarely are a problem in walnuts in Oregon, but they do occasionally infest a crop. Their white or pink larvae are up to 5/8 inch long and may enter and seriously damage the nuts. Their feeding within the husk may stain nut shells. The type of injury varies with the time of infestation. Early infestations arrest nut development and may result in heavy drop of nuts. Target your control sprays to the emergence of the second generation of codling moths, which occurs in the first part of July.

Diseases

Walnut blight is the most common disease of walnuts in Oregon (Figure 3). It is caused by a bacteria, Xanthomonas campestris pv. juglandis. The bacteria overwinter on infected buds and to a lesser extent in holdover cankers on twigs of the previous year’s growth.

During the spring growth period, bacteria are spread by raindrops to the current season’s growth. Frequent and prolonged rains just before, during, and after bloom result in severe blight outbreaks. This is the time when the nuts are most susceptible to infection. Three sprays of copper during the bloom period are recommended for walnut blight control. See Figure 4 for the growth stages to target.

Moss and lichens are not parasitic on walnut trees. They can, however, accumulate moisture, and in freezing weather the resulting ice increases weight on branches. A bordeaux or lime sulfur spray will control moss and lichen. A bordeaux spray applied for walnut blight control in the spring also helps control moss and lichens.

Deer damage

Deer are serious pests of young walnut trees, especially in outlying areas next to wooded areas. Deer fencing around the entire orchard or individual trees is the most reliable solution, but it is expensive. Special hunting licenses may be obtained for some rural locations.

Chemical repellents sometimes are partially successful. Bags of dried blood, bone meal and human hair hung in the trees are the most commonly used repellents. When replaced every two or three months, they are relatively successful.

Walnut fertilizer management

Good management practices are essential in order to achieve optimum responses to fertilizer. These practices include use of recommended varieties, selection of adapted soils, weed control, disease and insect control, and timely harvest.

Soil sampling and testing of fields to be planted to orchards is recommended. Soil analysis before planting is useful in predicting the need for potassium (K), magnesium (Mg) or lime applications. Application and incorporation into the soil of these elements is best done prior to planting. Follow recommended soil sampling procedures to estimate fertilizer needs. See A guide to collecting soil samples for farms and gardens.

Observations of annual shoot growth and the size and color of leaves and fruit can help you determine the trees’ fertilizer needs. In addition, leaf analysis indicates which elements are present in adequate, deficient, or excessive amounts (Table 1).

Apply nitrogen close to the start of active tree growth (March or April), according to Tables 2 and 3. Apply N in the fall only as needed to promote cover crop establishment and growth. If no cover crop is used, do not apply fall N.

| Nutrient | Deficiency | Below normal | Normal | Above normal | Excess |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nitrogen (% dry weight) | < 2.00 | 2.00-2.30 | 2.31-2.80 | 2.81-3.00 | > 3.00 |

| Phosphorus (% dry weight) | < 0.10 | 0.10-0.13 | 0.14-0.50 | 0.51-0.65 | > 0.65 |

| Potassium (% dry weight) | < 0.90 | 0.90-1.20 | 1.21-2.50 | 2.51-3.00 | > 3.00 |

| Sulfur (% dry weight) | < 0.07 | 0.07-0.10 | 0.11-0.20 | 0.21-0.50 | > 0.50 |

| Calcium (% dry weight) | < 0.80 | 0.80-1.10 | 1.11-2.50 | 2.51-3.00 | > 3.00 |

| Magnesium (% dry weight) | < 0.18 | 0.18-0.24 | 0.25-0.60 | 0.61-1.00 | > 1.00 |

| Manganese (ppm dry weight) | < 20 | 20-25 | 26-250 | 251-450 | > 450 |

| Iron (ppm dry weight) | < 40 | 40-50 | 51-400 | 401-500 | > 500 |

| Copper (ppm dry weight) | < 1 | 1–5 | 6–25 | 26-100 | > 100 |

| Boron (ppm dry weight) | < 60 | 60-85 | 86-150 | 151-200 | >200 |

| Zinc (ppm dry weight) | < 10 | 10–15 | 16-60 | 61-100 | > 100 |

| Age | Apply this amount of N (lb/tree) |

|---|---|

| Planting 1 year* | none |

| 2–5 | 1/3-1/2 |

| 6–7 | 1/2-3/4 |

| 8–10 | 3/4-1 |

*Apply N only after one growing season has passed. Young trees should grow 18 to 30 inches annually. As long as this much annual growth is attained, no nitrogen is needed.

| If leaf N in August is (%) | Apply this amount of N (lb/tree) |

|---|---|

| Less than 2.0 (severe deficiency) | 8–10 |

| 2.0-2.3 (deficiency) | 4–8 |

| 2.4-2.8 (optimal) | 2–4 |

| > 2.8 (excess) | none |

Broadcasting N under the outer half of the limb spread is most desirable. Band applications of N can be used but may lead to excessive acidity in the banded area.

Phosphorus (P)

In Oregon, walnut trees have not responded to applications of phosphorus.

Potassium (K)

Broadcast K and plow it under during preparation of land for planting (Table 4).

For mature trees, use leaf analysis to guide K application (Table 5). Since K applications tend to reduce magnesium uptake, do not apply K unless leaf analysis indicates a deficient or borderline level.

The K content of fertilizer is expressed as the oxide (K2 O) on fertilizer labels. Multiply K2 O by 0.83 to convert to K.

Preferably, drill K 4 to 6 inches deep in the root zone, or place it in a concentrated band on the soil surface. The band width should equal 2 inches per pound of K2 O applied. For example, if you apply 6 pounds of K2 O per tree, try to place it in a 12-inch band around the drip line.

If you use muriate of potash (potassium chloride), apply it in the fall or before mid-February to avoid chloride toxicity.

K levels in leaves often do not increase until the year following application. A single application of potassium usually is effective for 2 or more years.

| If OSU soil test for K reads (ppm) | Apply this amount of potassium (K2O) - (lb/A) |

|---|---|

| 0 to 75 | 300-400 |

| 76 to 150 | 200-300 |

| over 150 | none |

| If leaf K in August is (%) | Apply this amount of potassium (K2O) - (lb/tree) |

|---|---|

| 0.2-0.9 (deficiency) | 15-20 |

| 1.0-1.2 (borderline) | 0-15 |

| Over 1.2 (optimal) | 0 |

Boron (B)

Next to nitrogen, boron is the most deficient nutrient in Oregon walnut orchards. Boron deficiency symptoms consist of long, leafless shoots, mostly in the tops of trees. Shoots become flattened and twisted at the tips, resembling the head of a snake. These shoots die the following winter. Reduced yields by otherwise healthy trees frequently are due to boron deficiency.

If a laboratory leaf analysis shows boron levels are below 80 ppm, apply 0.25 to 0.5 lb B/tree to the soil (Table 6). Do not band soil-applied boron; broadcast it. Boron applications usually are effective for 2 to 3 years.

Spray application will produce more rapid recovery from B deficiency than soil application. However, spray-applied B is used up during the season in which it is applied. For current-season results, spray at the rate of 8 lb sodium pentaborate (Solubor) per acre, using 2 lb sodium pentaborate/100 gal of water. The boron spray can be combined with a copper blight spray. Follow up with a soil application of B, as suggested above.

| If leaf B in August is (ppm) | Apply this amount of B (mature trees) (lb/tree) |

|---|---|

| less than 80 | 0.25-0.5 |

| >80 | 0 |

If too much B is applied, an excessive crop of nuts may be set the following year, resulting in limb breakage and small nuts. Young trees less than 8 years old are more sensitive to boron. Where defi ciency symptoms on young trees indicate a need for boron fertilizer, do not exceed 0.1 lb B/tree.

Excessive boron applications can be toxic to trees. B toxicity is seen as round, brown dead spots along the margins of the leafl ets. In severe cases, spots also appear between the veins approaching the midrib. Nitrogen applications gradually reduce boron toxicity symptoms, and in about 3 years symptoms may be completely eliminated.

Magnesium (Mg)

Work Mg into the plow layer during preparation of the land for planting. If the soil test for Mg is less than 0.8 meq/100 g of soil, apply 1 ton dolomite/ acre. Dolomite acts much like limestone to correct soil acidity.

Lime

Apply lime if the soil pH is below 5.6. The amount of lime to apply is based on the SMP buffer test results (Table 7). This test measures a specific soil’s characteristics that influence its response to lime. The liming rate is based on 100-score lime.

Mix lime into the soil at least several weeks before planting. In established orchards, apply lime in the fall after harvest, so that winter rains can wash it into the trees’ root zone. A lime application is effective for five to seven years in orchards west of the Cascades.

| If the SMP buffer test for lime reads | Apply this amount of lime (ton/A) |

|---|---|

| less than 5.2 | 4-5 |

| 5.2-5.6 | 3-4 |

| 5.7-5.9 | 2-3 |

| 6.0-6.2 | 1-2 |

Pruning and training walnut trees

The objective of training a young walnut tree is to develop a tree with a strong system of main scaffold branches that can support a heavy crop of nuts, ice, or other stress. Limbs developed at a narrow angle to the trunk or main scaffold limb are structurally weak.

The modified central leader training system is recommended for walnuts. This system involves allowing a central leader or dominant shoot to extend straight up from the trunk. The scaffold branches are trained off this central leader. This system promotes formation of wide, strong branch angles on the scaffolds.

At planting, remove about half of the tops of the trees. Cut a 10-foot tree back to 5 feet and a 6-foot tree to 3 feet. After the tree is headed back, the top bud will form an upright terminal shoot (the central leader), where desired scaffold branches can be developed.

During the first, second, and third growing seasons, select three to five branches that will form the main framework of the tree. Remove excess branches. Cut off any buds that start to grow near the base of the tree. Space the scaffold branches with a foot or more of vertical distance between them. When all main branches arise just below the point where the tree is headed at planting, a structurally weak, vase-shape tree is formed.

Avoid large pruning cuts later by making cuts when shoots are small. Removing a shoot just after growth starts causes much less loss to a tree than allowing it to grow for one or more seasons and then removing it.

Gradually raise the height of the first limbs to the desired level by subsequent pruning. The limbs should be developed at a sufficient height to allow equipment to pass under them. After about 5 years, remove the central leader and begin using a multiple leader system.

The less a tree is pruned, the larger it will be. However, some pruning is necessary in order to build a strong, sturdy tree.

Pruning nonbearing trees

Pruning of nonbearing trees is simply a continuation of training. If shoot growth seems excessively long, head the terminals, especially in lower scaffold branches. Without this pruning, branches may grow so long that the first scaffold branches rest on the ground when weighted with a heavy crop, making cultivation and harvesting difficult.

Pruning bearing trees

Moderate pruning is needed every two or three years after trees come into bearing. Thin out the shoots in the tops of trees to maintain production throughout the trees. Remove drooping limbs that interfere with cultivation. Remove some, but not all, of the weak wood in the center of the trees. Often, late-developing catkins are produced on weak wood; these catkins shed pollen late and may pollinate late-blooming flowers.

Mature trees benefit from more intensive pruning. These trees often are so tall that a mechanical pruning tower is needed to get into the tree tops to do the required limb thinning. Cut many branches back 2 to 4 feet to strong side limbs.

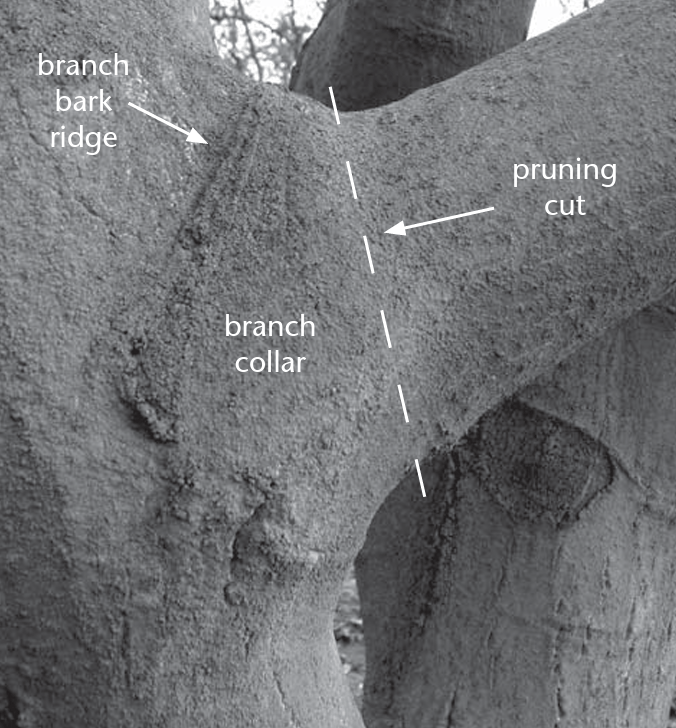

Always cut to a lateral branch so that you can preserve the branch collar (Figure 5). This will stimulate new growth near the cuts and allow more sunlight into the lower portions of the tree. Repeat this pruning every three to five years, depending on the tree’s growth and light distribution.

Rejuvenation pruning of winter-inquired trees requires cutting back to good, live wood. Wait a full year after the freeze, at which time it is easier to determine the extent of the injury. Retain all live wood. Make cuts on upright branches at a side branch and slant them to allow moisture to run off.

Harvesting and drying nuts

Walnuts are mature as soon as the husk will cut free from the nut, but they usually are not harvested until rains have cracked the husk to the point of letting the nut drop to the ground. This usually happens in October.

You can shake the limbs to loosen the nuts, so long as the bark is not damaged. You can grab and shake limbs with a long plastic pole with a hook on the end.

Mature walnuts lose quality rapidly after they have fallen, so gather fallen nuts frequently to prevent mold, discoloration, and decay. Kernels of nuts that remain on wet ground rapidly become discolored. Harvested, undried nuts left in the sack for more than a day or so may heat and become moldy.

If nuts are blown off by wind before the hulls crack, the hulls will ripen on the ground and usually can be removed after a week or two. Leave nuts on the ground until the hulls are loose. Walnut hulls contain compounds that stain and sometimes irritate sensitive skin, so use gloves when handling them.

Handling after harvest

Dry walnuts before eating or storing them. Begin the drying process within 24 hours of harvest. Nuts usually are dried in the shell, but you can save a considerable amount of drying time and use less heat if you shell the nuts before drying.

Walnuts are dry enough for storage when the divider between the nut halves breaks with a snap. If the divider is still rubbery, the nut is not dry enough.

Air circulation is at least as important as temperature during drying, so dry the nuts on a screen-bottomed tray, in an onion sack, or in any other container that will permit free air passage. Optimum drying temperatures are 95 to 105°F. If the temperature exceeds 110°F, nut quality will be poorer.

Small quantities of nuts can be dried in the warm air stream above a furnace or radiator as long as the temperature does not exceed 105°F. Drying may require three to four days. Nuts can be dried at lower temperatures, but more time is required.

Drying in a conventional oven is difficult because the lowest temperature setting is around 200°F and air circulation over the nuts is limited. Opening the oven door to lower the temperature is not energy-efficient.