Introduction

Beef cattle production is the major agricultural commodity in the state of Oregon and is mainly composed by cow-calf operations. In these operations, every section is important to the profitability of the production system, including breeding (bull selection and management, length of breeding season) and calving season, weaning, and development of replacement heifers. Among these sections, special attention should be given to the latter.

Replacement heifers bring new genetics and are the foundation on which the cowherd is built, being responsible for long-term herd productivity. In order to obtain optimal productivity, replacement heifers should attain puberty by 12 months of age, conceive for the first time at 15 months, and consequently calve around 2 years old (Lesmeister et al., 1973). Moreover, heifers that calve early during the first calving season wean more and heavier calves during their productive life, indicating the importance of an adequate management system for development of replacement heifers.

This article will focus on some strategies that beef producers have to improve heifer development programs and hence the entire profitability of cow-calf production systems.

How many replacement heifers should be kept?

The decision regarding how many replacement heifers should be kept in the herd depends on the direction that the operation goes. If the producer desires to maintain the size of the herd, the number of replacement heifers retained must be the same as the number of cows being culled during the year. On the other hand, if the producer wants to increase the herd size, the number of replacement heifers retained must be greater than the number of cows being culled.

Nevertheless, beef producers often do not have the option to choose if they want to include new animals in the herd, and inclusion of replacement heifers becomes totally dependent on the herd cull rate. This rate varies significantly and is mainly dependent on reproductive failure of mature cows during the breeding season. Several factors account for the reproductive failure, including poor nutrition, reproductive diseases as well as cow age. In commercial scenarios, the annual culling rates ranges from 15% to 50% and dictates the number of replacement heifers required to maintain or increase the cowherd size (Ritchie and Hawkins, BCH-1100).

Breed types, target age and weights

Breed is the factor that most impacts the age and weight in which replacement heifers reach sexual maturity and are capable of breeding. Bos taurus breeds are predominant in the Western U.S.; whereas B. indicus x B. taurus crosses are often encountered in the Southern U.S. Several studies reported that Brahman-influenced (B. indicus) heifers reach puberty at an older age (14 to 18 months of age) and with greater body weight (65% of mature weight) compared with B. taurus (12 to 14 months of age and 55% to 60% of mature weight, respectively) cohorts. Nonetheless, the physiological processes that influence the onset of puberty are exactly the same for both breed types, with the timing at which these processes occur being later in B. indicus cattle.

Age at puberty is also affected by several other environmental factors but mainly by nutritional management. Underfeeding results in lower number of heifers reaching puberty at the expected age and impaired decreased pregnancy rates during their first breeding season. Likewise, excessive feeding should also be avoided due to the increased expenses associated with feeding and excessive fat accretion into the heifer’s body. Excessive fat is known to have detrimental effects on expression of behavioral estrous, calving ease, conception rate, milk production and overall productivity of these females.

The “target weight” concept involves the achievement of a nutritional status that allows heifers to grow at a rate such that they are pubertal at the time of the breeding season. In mature cows, nutritional status is often assessed by using body condition score (1 to 9 scale, where 1 = emaciated and 9 = obese, see BEEF001).

Conversely, for developing replacement heifers, BCS may not be the best indicator of nutritional because these animals are not depositing excessive amounts of fat. Thus, BW assessment and average daily gain (ADG) calculation are the best indicators of growth and nutritional status of replacement heifers.

Another important point to remember is that the nutritional management of a replacement heifer is different from that of mature cows, meaning that it is extremely important to keep heifers and mature cows on separate nutritional programs. Table 1 shows the nutrient requirements for a pregnant replacement heifer and an adult cow, in a same mature body weight basis.

Months since conception

| Months since conception | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pregnant replacement heifer | TDN %DM | 50.5 | 50.5 | 50.7 | 50.9 | 51.4 | 52.3 | 53.8 | 56.2 | 59.9 |

| CP, %DM | 7.21 | 7.19 | 7.18 | 7.22 | 7.31 | 7.52 | 7.89 | 8.53 | 9.62 | |

| DMI, lb | 19.3 | 19.8 | 20.3 | 20.9 | 21.5 | 22.2 | 23.0 | 32.7 | 24.4 | |

| Target ADG | 0.88 | 0.88 | 0.88 | 0.88 | 0.88 | 0.88 | 0.88 | 0.88 | 0.88 | |

| Shrunk BW | 747 | 773 | 800 | 827 | 853 | 880 | 907 | 933 | 960 | |

| CA, % DM | 0.23 | 0.23 | 0.22 | 0.22 | 0.22 | 0.21 | 0.31 | 0.31 | 0.30 | |

| P, %DM | 0.18 | 0.18 | 0.18 | 0.17 | 0.17 | 0.17 | 0.23 | 0.23 | 0.22 | |

| Mature beef cow (1,200 lb mature weight) | TDN %DM | 57.6 | 56.21 | 54.7 | 53.4 | 44.9 | 45.8 | 47.1 | 49.3 | 52.3 |

| CP, %DM | 9.92 | 9.25 | 8.54 | 7.92 | 5.99 | 6.18 | 6.50 | 7.00 | 7.73 | |

| DMI, lb | 28.4 | 27.4 | 26.5 | 25.7 | 24.2 | 24.1 | 24.0 | 23.9 | 24.1 | |

| CA, % DM | 0.29 | 0.26 | 0.24 | 0.22 | 0.15 | 0.15 | 0.15 | 0.26 | 0.25 | |

| P, %DM | 0.19 | 0.18 | 0.17 | 0.15 | 0.12 | 0.12 | 0.12 | 0.16 | 0.16 | |

Specific management phases

Replacement heifers should be managed properly according to each period of their life. This management can be divided into five phases: growth before weaning (or preweaning), weaning to breeding, breeding, breeding to calving and calving to rebreeding. Nutrition plays an important role during each of these management phases; therefore, nutritional inputs should be carefully evaluated to ensure the economic viability of heifer development programs.

Preweaning

The goal of cow-calf systems is weaning healthy and productive calves, whether they are sold or maintained in the herd as replacement heifers. The goal for the preweaning phase is to economically produce calves that wean at adequate weight, age and body composition (muscle and fat content). In addition, weaning BW of replacement heifers is inversely associated with age at puberty, implying that heavier heifers often reach puberty sooner than lighter cohorts.

In most cow-calf production systems, nursing calves remain at the cow-calf ranch from birth to weaning, consuming primarily forages and milk. Considering that forage is the cheapest feed source in livestock operations and it is also during this period (from birth to weaning) that forages have the greatest nutritional quality and availability (from late spring to summer), beef producers should use it correctly in order to achieve desired cattle performance. However, for fall-calving herds, this scenario may not apply due to weather issues and consequent inadequate forage quality and/or availability.

Therefore, other nutritional strategies to improve calf performance exist, such as creep feeding. Creep feeding is an alternative that improves BW at weaning, “trains” animals to consume dry feeds in feed bunks and also alleviates the nutritional stresses associated with weaning. It is recommended the utilization of palatable grain mixes that contain a protein source (i.e., soybean meal or cottonseed meal), as well as molasses or dry alfalfa hay to increase palatability.

Weaning to breeding

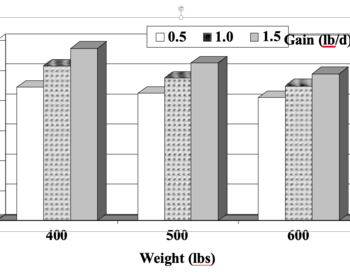

At the beginning of the breeding season, heifers should weigh 65% of their mature BW. Hence, the body weight at weaning will determine the amount of weight gain needed during this phase in order to ensure that replacement heifers are pubertal at least 42 days before the beginning of the breeding season. Usually, a daily gain of 1.0 to 1.5 pounds/day is sufficient to achieve this goal. If heifers are weaned at a lighter and less desired weight, post-weaning growth can be accelerated through nutrition but should not be greater than 2 pounds/day.

Breeding

During the breeding season, replacement heifers should be managed differently than mature cows. In general, replacement heifers should be bred earlier than the cow herd, which allows them to have additional time (at least 3 weeks) after their first calving to recover and join the mature cowherd for their second breeding season. Heifers that conceive earlier during their first breeding season wean more calves and heavier calves during their productive life.

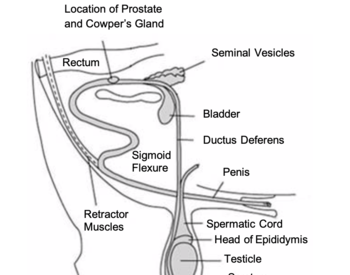

An additional strategy that can be adopted to maximize the number of heifers pregnant at the beginning of their first breeding season is estrus synchronization and artificial insemination (AI). These techniques allow more heifers to be bred in a shorter period during the breeding season and also a greater number of births at the beginning of the calving season. It is important to choose bulls with adequate calving ease, free of diseases (assessed by breeding soundness exam, if heifers are exposed to natural breeding), adequate scrotal circumference and libido.

Breeding to calving

At calving, heifers should have 85% of their mature BW. To achieve this goal, it is recommended that heifers gain around 1.0 pound/day during gestation. Nutrient requirements of pregnant replacement heifers are presented in Table 2. The pregnancy period is divided into three trimesters, with the third (and final) trimester being the most critical, given that this is the period where most of the calf development and colostrum production occur. However, it doesn’t mean the other two trimesters are not important. Recent research has demonstrated that organ differentiation and development occur during early gestation. Therefore, replacement heifers should be maintained in adequate nutrition and growth rate throughout the entire pregnancy.

| Months since conception | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| NEmrequired, Mcal/day | Maintenance | 6.46 | 6.63 | 6.80 | 6.97 | 7.14 | 7.30 | 7.47 | 9.08 | 10.06 |

| Growth | 2.56 | 2.63 | 2.70 | 2.77 | 2.83 | 2.90 | 2.97 | 3.03 | 3.10 | |

| Pregnancy | 0.03 | 0.06 | 0.14 | 0.29 | 0.58 | 1.07 | 1.88 | 3.12 | 4.88 | |

| Total | 9.05 | 9.33 | 9.64 | 10.03 | 10.55 | 11.28 | 12.32 | 15.24 | 18.03 | |

| MP required, g/day | Maintenance | 319 | 327 | 336 | 344 | 352 | 360 | 369 | 377 | 385 |

| Growth | 130 | 130 | 131 | 131 | 131 | 128 | 126 | 123 | 121 | |

| Pregnancy | 2 | 3 | 7 | 13 | 24 | 45 | 80 | 137 | 227 | |

| Total | 450 | 461 | 473 | 488 | 507 | 534 | 574 | 637 | 733 | |

| Calcium required, g/day | Maintenance | 11 | 12 | 12 | 13 | 13 | 13 | 14 | 14 | 15 |

| Growth | 10 | 10 | 9 | 9 | 9 | 9 | 9 | 9 | 8 | |

| Pregnancy | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 11 | 11 | 11 | |

| Total | 21 | 21 | 22 | 22 | 22 | 22 | 34 | 34 | 34 | |

| Phosphorus required, g/day | Maintenance | 9 | 9 | 9 | 10 | 10 | 10 | 11 | 11 | 11 |

| Growth | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 3 | 3 | |

| Pregnancy | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 6 | 6 | 6 | |

| Total | 13 | 13 | 13 | 14 | 14 | 14 | 20 | 21 | 21 | |

| ADG, lb/day | Growth | 0.95 | 0.95 | 0.95 | 0.95 | 0.95 | 0.95 | 0.95 | 0.95 | 0.95 |

| Pregnancy | 0.06 | 0.09 | 0.15 | 0.24 | 0.38 | 0.56 | 0.81 | 1.14 | 1.54 | |

| Total | 1.01 | 1.05 | 1.10 | 1.19 | 1.33 | 1.51 | 1.76 | 2.09 | 2.49 | |

| Body weight, lb | Shrunk body | 809 | 838 | 867 | 896 | 924 | 953 | 982 | 1011 | 1040 |

| Gravid uterus mass | 3 | 5 | 9 | 15 | 24 | 38 | 59 | 88 | 129 | |

| Total | 812 | 843 | 876 | 911 | 949 | 992 | 1041 | 1099 | 1169 | |

Calving to rebreeding

As previously mentioned, heifers should be managed to calve with 85% of their mature BW, as well as adequate BCS (around 6). Adequate BW and BCS at calving result in reduced postpartum period (from calving to rebreeding) and earlier resumption of estrous cycles. Moreover, heifers in adequate BW and BCS will have higher quality and amount of colostrum produced, reduced dystocia and calf death loss, as well as increased calf vigor.

It is important to remember how critical the post-calving period for the heifer is. After calving, heifers need to produce milk, maintain adequate growth rate and become fertile again prior to the subsequent breeding season when they should be at 90% of their mature BW. Heifers also often require more assistance during calving and have higher incidence of dystocia compared with mature cows. For more information and management practices used to assist and detect an animal with dystocia, please refer to the Calving School Handbook – Oregon State University.

Strategies to hasten heifer development

It is extremely important to adopt and/or develop feasible strategies that hasten heifer development, consequently improving the profitability of the beef production system. Several strategies have been developed, and some of those will be presented in this section.

Nutrition and management opportunities

As previously mentioned, nutrition is one of the most important factors affecting the age and BW at which heifers reach puberty. Nutrition, mainly energy intake, is the primary consideration associated with nutrition and reproductive performance in beef cattle. Energy intake is positively correlated with blood compounds (glucose, insulin, progesterone, and insulin-like growth factor I [IGF-I]) that affect reproductive performance of cows and puberty attainment in beef heifers (Cooke et al., 2007). Heifers receiving diets and/or additives (see below) that promote ruminal propionate (primary gluconeogenic compound for the ruminant) synthesis and subsequent glucose production reach puberty at an earlier age and at lighter weight.

Another management alternative to hasten heifer reproductive development is to acclimate them to human handling/interaction after weaning. Recent data from our research group demonstrated that, independently of the genetics (B. taurus [Angus x Hereford] and B. indicus [Brahman- crossbred]), heifers acclimated to human handling reached puberty earlier compared with non-acclimated cohorts (Cooke et al., 2009; 2012). Briefly, the effects of acclimation rely on reduced plasma concentrations of cortisol (stress hormone), which directly affects the production and release of hormones associated with puberty attainment.

Growth promoters and feed additives

Growth promoters (i.e., zeranol and estradiol) have been shown to increase daily gain in stocker and finishing beef cattle. Similarly, replacement heifers implanted with growth promoters have increased body weight gain, pelvic area and milk production and wean heavier calves compared with non-implanted cohorts. However, no significant effects were observed on the reproductive performance (pregnancy rates) of animals implanted or not with growth promoters.

Feed additives, such as monensin and lasalocid, act by inhibiting a specific class of rumen bacteria (gram-positive) and result in reduced energy waste (lactate, methane, and carbon dioxide production) and increased propionate synthesis in the rumen.

Hence, these feed additives are known to increase body weight gain, as well as decrease the incidence of digestive problems (bloat and acidosis) in feedlot and grazing cattle. Moreover, these feed additives are also expected to benefit reproductive development of heifers due to increased ruminal propionate production, feed efficiency, ruminal health and body weight gain.

Bull exposure (or biostimulation)

This technique consists of the stimulatory effects of a male on estrus and ovulation of females through genital stimulation, pheromones or other external cues. Exposing replacement heifers to surgically altered bulls (not capable of breeding) has been shown to decrease age at puberty up to 90 d (Rekwot et al., 2000), hence increasing the number of pregnant heifers (up to 42 %) in the first 21 d of the breeding season (Roberson et al., 1991).

Conclusions

In conclusion, the development of replacement heifers is an important component within cow-calf production systems and requires special attention by the beef producer. Heifers should reach puberty by 12 months of age, conceive by 15 months of age, and calve at 2 years old to maximize their lifetime productivity. Productive and development goals are particular to each phase within heifer development programs, including pre- and post-weaning management as well as breeding, pregnancy and calving seasons. Hence, nutritional and management approaches to improve heifer development should be specific to each development phase in order to improve the profitability of cow-calf systems.

References

Cooke et al. 2007. J. Anim. Sci. 85:2564-2574.

Cooke et al. 2009. J. Anim. Sci. 87:3403-3412.

Cooke et al. 2012. J. Anim. Sci. 90:3547-3555.

Lesmeister et al. 1973. J. Anim. Sci. 36:1-6.

NRC. 1996. National Requirements of Beef Cattle.

National Academy Press, Washington, DC.

Rekwot et al. 2000. Reprod. Nutr. Dev. 40:359-367.

Ritchie, H. D. and D. R. Hawkins. Beef Cattle Handbook – Iowa Beef Center (BCH-1100).

Roberson et al. 1991. J. Anim. Sci. 69:2092-2098.

This document is part of the Oregon State University – Beef Cattle Library. Prior to acceptance, this document was anonymously reviewed by two experts in the area.